![]() Section VI

Section VI

Practical Issues for Travellers![]()

Chapter 24

Travelling with Children (Including International Adoption Issues)

Philip R. Fischer1 and Andrea P. Summer2

1Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, US

2Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston, South Carolina, US

Introduction

The principles guiding the practice of travel medicine are fairly constant regardless of the age of the traveller. The application of these principles, however, varies markedly between children and adults. Children are not merely ‘little adults’. Children are unique in regard to size, development, behavioural risks, immune maturity and tolerance of medications. Reviewing available data, this chapter gives practical guidance for medical practitioners providing care to children travelling internationally.

Millions of children cross international borders each year, and lives are frequently enriched from foreign experiences. Clearly, each specific trip carries its own individualised benefits and risks. Every travelling child faces issues of comfort, safety, exposure to germs and readaptation. Pre-travel guidance can help families maximise the benefits of international travel for their children while minimising the health risks. Following travel, personally tailored evaluation and care can also facilitate a healthy entry or re-entry to the ongoing living situation.

In recent years, there has been increased interest in the particular needs of travelling children. Several review articles cover broad areas of paediatric travel medicine [1–9].

Malaria and Other Insect-Borne Diseases

Geographical considerations regarding the need for protection from malaria and other insect-borne diseases are similar for children and adults. Within endemic areas, however, the need for protection for children is a critical concern. Children can become very ill very quickly, and they do not always show easily localised signs of infection. Many different illnesses present with fever in children, and even where medical care is good, delayed diagnosis of malaria is common [10, 11]. Children carry the greatest burden of malaria’s morbidity and mortality, so careful prevention is necessary for any child spending time in a malaria-endemic area.

No single intervention is 100% protective, and a multifaceted approach to the prevention of insect-borne diseases is needed. Vaccination and chemoprophylaxis are not available for many diseases transmitted by insects, thus the avoidance of bites by mosquitoes and other insects should be a primary focus.

Personal Protective Measures

Adults travelling with children should be advised particularly to dress children comfortably with clothes exposing minimal amounts of skin and to keep the children in ‘mosquito-free zones’ during the evening and night hours. Rooms with closed doors and screened windows can keep many of the biting insects away from vulnerable young travellers. Expatriates and others spending prolonged periods in malaria-endemic areas should be advised to avoid leaving stagnant water (a breeding site for mosquitoes) around their dwellings.

Bed nets are available commercially in forms that can fit over a variety of cribs and beds where children might be sleeping. Impregnating bed nets or even curtains with insecticides can also help to protect individuals and has even been shown to decrease morbidity in communities [12–14]. Permethrin-impregnated clothes and pyrethroid-impregnated bed nets are safe for use by children and can offer weeks (clothes) to months (bed nets) of protection after a single impregnation.

N,N-diethyl-meta-toluamide (DEET) is the ‘gold standard’ for efficacy as an insect repellent and has been used by hundreds of millions of people of all ages over the past four decades. Newer repellents such as those containing citronella seem to be much less effective [15]. Nonetheless, there has been controversy over the safety of DEET-containing insect repellents in children.

Is DEET safe for use in young children? Millions of children use DEET each year, and there have been very few reports of adverse outcomes in children who were using DEET [16]. Some of the unfortunate children with poor outcomes had underlying metabolic abnormalities [17] or applied too much DEET too frequently over unnecessarily extensive body areas [18–20]. Another child with an apparent adverse reaction had apparently licked DEET off her skin and ingested it orally [21]. Details of exposure to DEET are less clear in the other reported cases [22].

More recently, according to the DEET Registry, a post-marketing surveillance system that generates details on medical events temporally associated with DEET use, 296 cases of moderate to major severity were reported from 1995 to 2001 [23]. However, of these cases, only 36 (14.5%) were determined to be probably related and 157 (65%) possibly related to DEET exposure. Approximately 40% of these events occurred in children under 20 years of age, 42% of whom experienced a seizure. No definite relationship between DEET concentration and case severity could be elucidated. The authors concluded that given the extensive use of DEET in the US and the inherent limitations of using passively reported data, the risk of serious adverse events related to the use of DEET repellents is likely minimal [23].

Clearly, DEET has been associated very rarely with tragic outcomes, but there is no clear evidence of causality. In cases where details were available, the exposure seemed to be either oral or over extensive skin surfaces in frequent applications. How should travel medicine practitioners interpret these data? DEET is effective and is safely used by millions of children each year. It spares the inconvenience of insect bites and the risk of insect-borne disease. The use of DEET should be encouraged, but it should be used prudently. It should only be applied on exposed skin, and most of the skin should be covered with clothes. Travel medicine practitioners should remind parents that DEET should not be ingested orally. Thus, special attention should be placed on young children who lick their hands and arms. The concentration of DEET relates to the duration of effective protection but not to the risk of toxicity. Thus, DEET use by children can be encouraged with attention paid to using it only on the few areas of skin that are exposed to insects.

An effective alternative to DEET, picaridin, has been used extensively in Europe and Latin America and is now also recommended for use in the United States by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Picaridin has minimal oral, dermal and inhalation toxicity, and is felt to be safe for children of all ages. Higher concentrations of picaridin (≥19.2%) should be used in areas where life-threatening infections may be transmitted by mosquitoes since formulations of 5–10% provide only around 2 hours of protection. When used in 19.2% concentration, picaridin has been shown to provide similar or better protection than similar concentrations of DEET in both daytime and night-time testing [24].

Personal protective measures are critically important, but they are not universally practised or completely protective. Thus, chemoprophylaxis should be advised for travellers to areas where malaria is endemic. Protective immunity to malaria develops slowly over 2–5 years in children, so prophylactic medications can be necessary for years, despite ongoing exposure to malaria parasites.

Malaria Chemoprophylaxis and Treatment

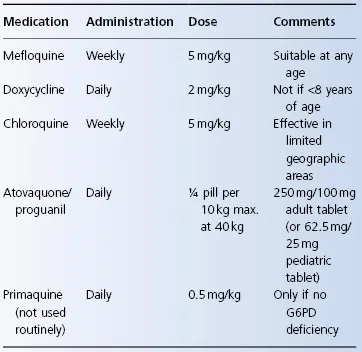

The geography of medication resistance by Plasmodium parasites is not age-dependent. Nonetheless, the delivery of medication to children differs from that to adults. Dosing details are noted in Table 24.1.

Table 24.1 Malaria chemoprophylaxis in children

Mefloquine seems to be fully effective and safe in children. Despite past hesitation to use mefloquine in young infants, no significant toxic effects were reported. Its use is now accepted for children of any age. As in adults, mefloquine would not be given routinely to a child with a history of cardiac dysrhythmia or with a known psychiatric disorder. Attention deficit disorder and other behavioural problems have not been associated with mefloquine-induced toxicity. Children with active seizure disorders, however, should not take mefloquine. Since some children with simple febrile seizures go on to develop recurrent epileptiform seizures, it is probably best to be judicious about mefloquine use in children less than 6 years old with a history of a previous febrile convulsion. However, since mefloquine is an excellent prophylactic agent in many areas, individualised decisions should be made, weighing the known risk of severe malaria with the unknown but probably small risk of serious mefloquine toxicity in a particular child.

Mefloquine, however, does not taste good, and it is not available in a liquid form. Weekly doses can be weighed and placed by a pharmacist into capsules; capsules can then be opened each week to give the appropriate dose of powdered mefloquine to the child. Alternatively, pills can be cut in quarters with doses rounded off to the nearest quarter pill to be given weekly. Anecdotal reports suggest that the taste of mefloquine is better tolerated when mixed with chocolate or cola-containing soft drinks.

The combination of atovaquone and proguanil has also been studied in children and appears to be safe and effective for children >11 kg [25]. Even though prophylactic dosing of atovaquone/proguanil has not been formally studied in children weighing 5–11 kg, data have been extrapolated to provide dosing recommendations for children in this weight range [26].

Doxycycline is associated with discoloration of developing teeth and might adversely affect the growth of long bones. It is, thus, generally not used in children less than 8 years of age in North America or less than 12 years of age in the UK among other countries.

Chloroquine is safe in children and is effective against the malaria present in a few geographical areas of the world (primarily Central America). Even with long-term weekly use, toxicity has not been noted. Nonetheless, ocular damage has been reported with large doses of chloroquine used over shorter periods of time. Thus, chloroquine use in a child for more than 5 consecutive years should be undertaken only in careful consultation with an ophthalmologist who is following the condition of the child’s retinas. As in adults, other rare but reversible adverse effects are possible. Similarly to children using mefloquine, most children do not enjoy the taste of chloroquine, but attempts to ‘hide’ the taste may help.

The combination of sulfadoxine and pyrimethamine, like other sulfa-containing products, carries about a 1 in 5,000 risk of life-threatening Stevens–Johnson syndrome. Furthermore, unacceptably high rates of treatment failure have been observed when...