eBook - ePub

Improving Performance

How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Improving Performance

How to Manage the White Space on the Organization Chart

About this book

Improving Performance is recognized as the book that launched the Process Improvement revolution. It was the first such approach to bridge the gap between organization strategy and the individual. Now, in this revised and expanded new edition, Gary Rummler reflects on the key needs of organizations faced with today's challenge of managing change in today's complex world. The book shows how to apply the three levels of performance and link performance to strategy, move from annual programs to sustained performance improvement, redesign processes, overcome the seven deadly sins of performance improvement and much more.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Improving Performance by Geary A. Rummler,Alan P. Brache in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Human Resource Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE

A FRAMEWORK FOR IMPROVING PERFORMANCE

CHAPTER ONE

VIEWING ORGANIZATIONS AS SYSTEMS

Adapt or die.—UNKNOWN

The Traditional (Vertical) View of an Organization

Many managers don’t understand their businesses. Given the recent “back to basics” and “stick to the knitting” trend, they may understand their products and services. They may even understand their customers and their competition. However, they often don’t understand at a sufficient level of detail how their businesses get products developed, made, sold, and distributed. We believe that the primary reason for this lack of understanding is that most managers (and nonmanagers) have a fundamentally flawed view of their organizations.

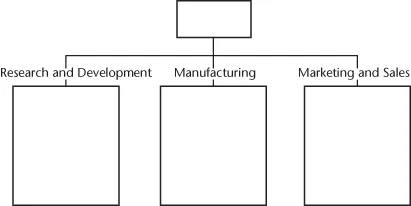

When we ask a manager to draw a picture of his or her business (be it an entire company, a business unit, or a department), we typically get something that looks like the traditional organization chart shown in Figure 1.1. While it may have more tiers of boxes and different labels, the picture inevitably shows the vertical reporting relationships of a series of functions.

FIGURE 1.1. TRADITIONAL (VERTICAL) VIEW OF AN ORGANIZATION

As a picture of a business, what’s missing from Figure 1.1? First of all, it doesn’t show the customers. Second, we can’t see the products and services we provide to the customers. Third, we get no sense of the work flow through which we develop, produce, and deliver the product or service. Thus, Figure 1.1 doesn’t show what we do, whom we do it for, or how we do it. Other than that, it’s a great picture of a business. But, you may say, an organization chart isn’t supposed to show those things. Fine. Where’s the picture of the business that does show those things?

In small or new organizations, this vertical view is not a major problem because everybody in the organization knows each other and needs to understand other functions. However, as time passes and the organization becomes more complex as the environment changes and technology becomes more complicated, this view of the organization becomes a liability.

The danger lies in the fact that when managers see their organizations vertically and functionally (as in Figure 1.1), they tend to manage them vertically and functionally. More often than not, a manager of several units manages those units on a one-to-one basis. Goals are established for each function independently. Meetings between functions are limited to activity reports.

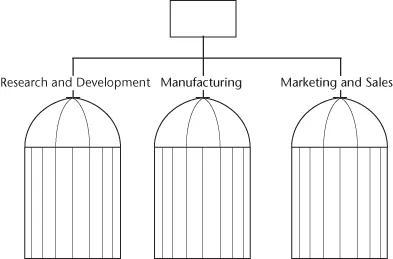

In this environment, subordinate managers tend to perceive other functions as enemies, rather than as partners in the battle against the competition. “Silos”—tall, thick, windowless structures, like those in Figure 1.2—are built around departments. These silos usually prevent interdepartmental issues from being resolved between peers at low and middle levels. A cross-functional issue around scheduling or accuracy, for example, is escalated to the top of a silo. The manager at that level addresses it with the manager at the top of the other silo. Both managers then communicate the resolution down to the level at which the work gets done.

FIGURE 1.2. THE “SILO” PHENOMENON

The silo culture forces managers to resolve lower-level issues, taking their time away from higher-priority customer and competitor concerns. Individual contributors, who could be resolving these issues, take less responsibility for results and perceive themselves as mere implementers and information providers. This scenario is not even the worst case. Often, function heads are so at odds that cross-functional issues don’t get addressed at all. In this environment, one often hears of things falling between the cracks or disappearing “into a black hole.”

As each function strives to meet its goals, it optimizes (gets better and better at “making its numbers”). However, this functional optimization often contributes to the suboptimization of the organization as a whole. For example, marketing and sales can achieve its goals and become a corporate hero by selling lots of products. If those products can’t be designed or delivered on schedule or at a profit, that’s research and development’s, manufacturing’s, or distribution’s problem; sales did its job. Research and development can look good by designing technically sophisticated products. If they can’t be sold, that’s sales’ problem. If they can’t be made at a profit, that’s manufacturing’s problem. Finally, manufacturing can be a star if it meets its yield and scrap goals. If the proliferation of finished goods sends inventory costs through the roof, that’s the concern of distribution, or marketing, or perhaps finance. In each of these situations, a department excels against traditional measures and, in so doing, hurts the organization as a whole.

In the good old days of a seller’s market, it didn’t matter. A company could introduce products at its own pace, meet only its own internal quality goals, and set prices that guaranteed adequate margins. There were no serious consequences to the evolution of functional silos like those illustrated in the examples. Those days are over. Today’s reality requires most organizations to compete in a buyer’s market. We need a different way to look at, think about, and manage organizations.

The Systems (Horizontal) View of an Organization

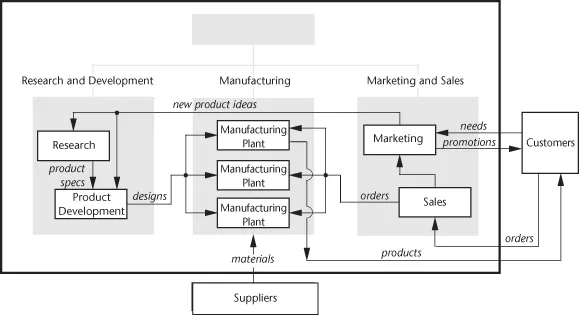

A different perspective is represented by the horizontal, or systems, view of an organization, illustrated in Figure 1.3. This high-level picture of a business:

- Includes the three ingredients missing from the organization chart depicted in Figure 1.1: the customer, the product, and the flow of work

- Enables us to see how work actually gets done, which is through processes that cut across functional boundaries

- Shows the internal customer-supplier relationships through which products and services are produced

FIGURE 1.3. SYSTEMS (HORIZONTAL) VIEW OF AN ORGANIZATION

In our experience, the greatest opportunities for performance improvement often lie in the functional interfaces—those points at which the baton (for example, “production specs”) is being passed from one department to another. Examples of key interfaces include the passing of new product ideas from marketing to research and development, the handoff of a new product from research and development to manufacturing, and the transfer of customer billing information from sales to finance. Critical interfaces (which occur in the “white space” on an organization chart) are visible in the horizontal view of an organization.

An organization chart has two purposes:

- It shows which people have been grouped together for operating efficiency and for human resource development.

- It shows reporting relationships.

For these purposes, the organization chart is a valuable administrative convenience. However, it should not be confused with the “what,” “why,” and “how” of the business; all too often, it’s the organization chart, not the business, that’s being managed. Managers’ failure to recognize the horizontal organization explains their most common answer to the question “What do you do?” They say (to refer to Figure 1.1), “I manage A, B, and C.” Assuming that A, B, and C already have competent managers, we have to ask if the senior manager sees his or her job as remanaging those functions. If so, is that a role that justifies his or her salary? We don’t believe so. A primary contribution of a manager (at the second level or above) is to manage interfaces. The boxes already have managers; the senior manager adds value by managing the white space between the boxes.

In our experience, the systems view of an organization is the starting point—the foundation—for designing and managing organizations that respond effectively to the new reality of cutthroat competition and changing customer expectations.

The Organization as an Adaptive System

Our framework is based on the premise that organizations behave as adaptive systems. As Figure 1.4—often called a “super-system map”—shows, an organization is a processing system (1) that converts various resource inputs (2) into product and service outputs (3), which it provides to receiving systems, or markets (4). It also provides financial value, in the form of equity and dividends, to its shareholders (5). The organization is guided by its own internal criteria and feedback (6) but is ultimately driven by the feedback from its market (7). The competit...

Table of contents

- COVER

- TABLE OF CONTENTS

- TITLE

- COPYRIGHT

- LIST OF FIGURES AND TABLES

- FOREWORD

- PREFACE

- THE AUTHORS

- PART ONE: A FRAMEWORK FOR IMPROVING PERFORMANCE

- PART TWO: EXPLORING THE THREE LEVELS OF PERFORMANCE

- PART THREE: APPLYING THE THREE LEVELS OF PERFORMANCE

- INDEX

- INSTRUCTOR’S GUIDE

- End User License Agreement