Annual Plant Reviews, Plant Polysaccharides

Biosynthesis and Bioengineering

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

The volume focuses on the evolution of the many families of genes whose products are required to make a particular kind of polysaccharide, bringing attention to the specific biochemical properties of the proteins to the level of kinds of sugar linkages they make.

Beautifully illustrated in full colour throughout, this exceptional new volume provides cutting edge up-to-date information on such important topics as cell wall biology, composition and biosynthesis, glycosyltransferases, hydroxyproline-rich glycoproteins, enzymatic modification of plant cell wall polysaccharides, glycan engineering in transgenic plants, and polysaccharide nanobiotechnology.

Drawing together some of the world's leading experts in these areas, the editor, Peter Ulvskov, has provided a landmark volume that is essential reading for plant and crop scientists, biochemists, molecular biologists and geneticists. All libraries in universities and research establishments

where plant sciences, agriculture, biological, biochemical and molecular sciences are studied and taught should have copies of this important volume.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

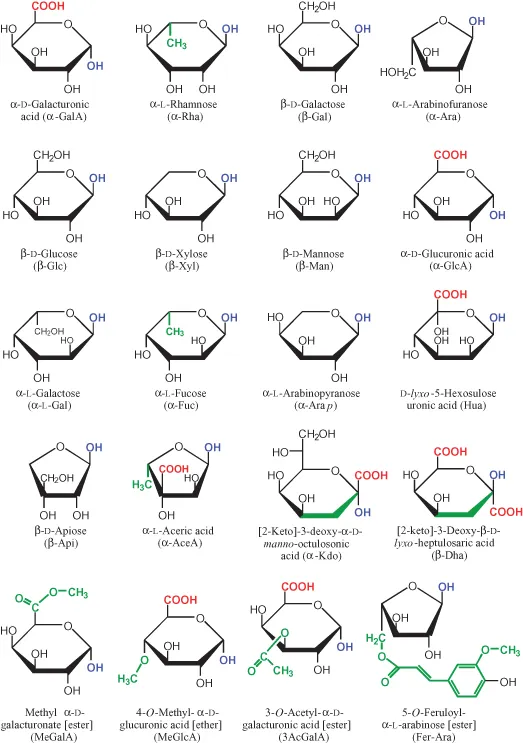

The monosaccharides are shown as hemiacetal or hemiketal rings. However, within a polysaccharide, each sugar (except one, the reducing terminus) is present as an acetal or ketal residue, the term ‘residue’ implying that it is ‘what remains’ after losing the –OH group (shown in blue) from the anomeric carbon (the anomeric carbon is the one with single-bonds to two oxygens; it is here drawn as the right-hand extremity of the hexagon or pentagon). In a sugar residue of a polysaccharide, this particular –OH group has departed (in the form of H2O), ‘taking with it’ one oxygen-linked H atom from the next sugar along the polysaccharide chain. The one sugar of the polysaccharide that is not strictly a residue is the reducing terminus, so called because it has not lost its anomeric –OH group and in aqueous solution can therefore equilibrate with the straight-chain form, which possesses an oxo group (C=O, which has reducing properties).

All but two of the sugars shown are aldoses (i.e. the anomeric carbon has only one additional C atom attached to it), but Kdo and Dha are ketoses (the anomeric C is attached to two other carbons). (Hua has two anomeric carbons (C-1 and C-5) and is both an aldose and a ketose.) In aqueous solution, each illustrated hemiacetal and hemiketal equilibrates with a small percentage of a straight-chain form possessing an oxo group (an aldehyde or ketone, in aldoses and ketoses respectively) – hence the slightly redundant term ‘keto’ in the names of Kdo and Dha.

Each named sugar could theoretically occur as two isomeric forms (enantiomers, designated D- and L-), distinguished by the orientation of the C–O bond of the penultimate C atom. Galactose is the only wall residue known to occur as both D- and L-enantiomer. Note that D- and L-Gal differ in orientation of the C–O bond at all four non-anomeric, chiral centres (= carbons 2, 3, 4 and 5; the difference at C-5 is indicated by the placement of the –CH2OH group).

The linkage between a sugar residue and the next building-block along a polysaccharide chain can be in either of two isomeric forms (anomers, designated α- and β-) defined by the orientation of the bond between the anomeric C atom and the oxygen atom (shown in blue) that bridges the two sugars: if this C–O bond has the same orientation as that of the penultimate C atom, then the residue is α-; if opposite, β-. This means that, in these Haworth formulae, the –OH of the anomeric carbon points down in α-D- and β-L-sugars, and up in β-D- and α-L-sugars.

The sugar ring can be 6-membered (pyranose; -p) or 5-membered (furanose; -f). Api and AceA must be -f because of the absence of an oxygen on a C-5, and MeGlcA can only be -p. Ara occurs in both forms. All the others could theoretically occur in either form, but in practice occur only in the -p form illustrated.

Each sugar residue is attached, via its anomeric carbon, to an –OH group on the following sugar unit in the polysaccharide chain. Usually, there are several such –OH groups to choose from (e.g., in the case of Glcp, on carbons 2, 3, 4 or 6: the linkage is designated (1→2), (1→3), (1→4) or (1→6), accordingly). However, a given sugar unit (either a residue or the reducing terminus) can and often does have more than one sugar residue attached to it.

Once it has become part of a polysaccharide chain, a given sugar residue is ‘locked’ in one of the four possible ring forms (α-p, β-p, α-f, or β-f). These ring forms have a huge impact on the polysaccharide, as is obvious from the enormous differences in physical, chemical and biological properties between amylose and cellulose (which are α-p and β-p, respectively, but otherwise identical).

Although illustrated here in unionized form, the free carboxy groups (–COOH, shown in red) would often be negatively charged (–COO−) under physiological conditions of pH. Relatively hydrophobic (non-polar) groups are shown in green.

Abbreviations: The diagrams show (in parentheses) the shorthand used throughout this chapter. Thus, unless otherwise stated in the text, the ring-form (-p or -f) and enantiomer (D- or L-) are assumed to be as illustrated here; for example, ‘β-Gal’ implies β-D-Galp unless specified as L-Gal. Other abbreviations used (not illustrated): MeXyl, 2-O-methyl-α-D-Xylp (ether); MeFuc, 2-O-methyl-α-L-Fucp (ether); MeRha, 3-O-methyl-α-L-Rhap (ether); MeGal, 3-O-methyl-D-Galp (ether); 5AcAra, 5-O-acetyl-L-Araf (ester); 6AcGal, 6-O-acetyl-D-Galp (ester); 6AcGlc, 6-O-acetyl-D-Glcp (ester); ΔUA, a 4,5-unsaturated, 4-deoxy derivative of GalA or GlcA.

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Series page

- PREFACE

- DEDICATION

- CONTRIBUTORS

- Chapter 1 CELL WALL POLYSACCHARIDE COMPOSITION AND COVALENT CROSSLINKING

- Chapter 2 DISSECTION OF PLANT CELL WALLS BY HIGH-THROUGHPUT METHODS

- Chapter 3 APPROACHES TO CHEMICAL SYNTHESIS OF PECTIC OLIGOSACCHARIDES

- Chapter 4 ANNOTATING CARBOHYDRATE-ACTIVE ENZYMES IN PLANT GENOMES: PRESENT CHALLENGES

- Chapter 5 BIOSYNTHESIS OF PLANT CELL WALL AND RELATED POLYSACCHARIDES BY ENZYMES OF THE GT2 AND GT48 FAMILIES

- Chapter 6 GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASES OF THE GT8 FAMILY

- Chapter 7 GENES AND ENZYMES OF THE GT31 FAMILY: TOWARDS UNRAVELLING THE FUNCTION(s) OF THE PLANT GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASE FAMILY MEMBERS

- Chapter 8 GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASES OF THE GT34 AND GT37 FAMILIES

- Chapter 9 GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASES OF THE GT43 FAMILY

- Chapter 10 GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASES OF THE GT47 FAMILY

- Chapter 11 THE PLANT GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASE FAMILY GT64: IN SEARCH OF A FUNCTION

- Chapter 12 GLYCOSYLTRANSFERASES OF THE GT77 FAMILY

- Chapter 13 HYDROXYPROLINE-RICH GLYCOPROTEINS: FORM AND FUNCTION

- Chapter 14 PLANT CELL WALL BIOLOGY: POLYSACCHARIDES IN ARCHITECTURAL AND DEVELOPMENTAL CONTEXTS

- Chapter 15 ENZYMATIC MODIFICATION OF PLANT CELL WALL POLYSACCHARIDES

- Chapter 16 PRODUCTION OF HETEROLOGOUS STORAGE POLYSACCHARIDES IN POTATO PLANTS

- Chapter 17 GLYCAN ENGINEERING IN TRANSGENIC PLANTS

- Chapter 18 POLYSACCHARIDE NANOBIOTECHNOLOGY: A CASE STUDY OF DENTAL IMPLANT COATING

- Index