eBook - ePub

Virtual Screening

Principles, Challenges, and Practical Guidelines

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Virtual Screening

Principles, Challenges, and Practical Guidelines

About this book

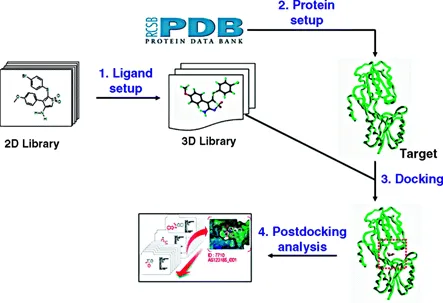

Drug discovery is all about finding small molecules that interact in a desired way with larger molecules, namely proteins and other macromolecules in the human body. If the three-dimensional structures of both the small and large molecule are known, their interaction can be tested by computer simulation with a reasonable degree of accuracy. Alternatively, if active ligands are already available, molecular similarity searches can be used to find new molecules. This virtual screening can even be applied to compounds that have yet to be synthesized, as opposed to "real" screening that requires cost- and labor-intensive laboratory testing with previously synthesized drug compounds.

Unique in its focus on the end user, this is a real "how to" book that does not presuppose prior experience in virtual screening or a background

in computational chemistry. It is both a desktop reference and practical guide to virtual screening applications in drug discovery, offering a comprehensive and up-to-date overview. Clearly divided into four major sections, the first provides a detailed description of the methods required for and applied in virtual screening, while the second discusses the most important challenges in order to improve the impact and success of this technique. The third and fourth, practical parts contain practical guidelines and several case studies covering the most

important scenarios for new drug discovery, accompanied by general guidelines for the entire workflow of virtual screening studies.

Throughout the text, medicinal chemists from academia, as well as from large and small pharmaceutical companies report on their experience and pass on priceless practical advice on how to make best use of these powerful methods.

Unique in its focus on the end user, this is a real "how to" book that does not presuppose prior experience in virtual screening or a background

in computational chemistry. It is both a desktop reference and practical guide to virtual screening applications in drug discovery, offering a comprehensive and up-to-date overview. Clearly divided into four major sections, the first provides a detailed description of the methods required for and applied in virtual screening, while the second discusses the most important challenges in order to improve the impact and success of this technique. The third and fourth, practical parts contain practical guidelines and several case studies covering the most

important scenarios for new drug discovery, accompanied by general guidelines for the entire workflow of virtual screening studies.

Throughout the text, medicinal chemists from academia, as well as from large and small pharmaceutical companies report on their experience and pass on priceless practical advice on how to make best use of these powerful methods.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part One

Principles

Chapter 1

Virtual Screening of Chemical Space: From Generic Compound Collections to Tailored Screening Libraries

1.1 Introduction

Today's challenge of making the drug discovery process more efficient remains unchanged. The need for developing safe and innovative drugs, under the increasing pressure of speed and cost reduction, has shifted the focus toward improving the early discovery phase of lead identification and optimization. “Fail early, fail fast, and fail cheap” has often been quoted as the key principle contributing to the overall efficiency gain in drug discovery. While high-throughput screening (HTS) of large compound libraries is still the major source for discovering novel hits in the pharmaceutical industry, virtual screening has made an increasing impact in many areas of the lead identification process and has evolved into an established computational technology in modern drug discovery over the past 10 years.

Traditionally, virtual screening is conducted simply by searching the company proprietary database of its compound collections, and this approach continues to be a mainstream application. However, the continuous development of novel and more sophisticated virtual screening methods has opened up the possibility to search also for compounds that do not necessarily exist in physical form in a screening collection. Such compounds can be obtained either from a multitude of external sources, such as compound libraries from commercial vendors, or from public or commercial databases. Even more, virtual screening can deal with molecules that purely exist as virtual entities derived from de novo design ideas or enumeration of combinatorial libraries. Taken to its extreme, any molecule conceivable by the human mind can in theory be evaluated by virtual screening. This has led to the concept of chemical space comprising the entire collection of all possible molecules – real and imaginary – that could be created. Since such a chemical space is huge, it is crucial for the success of drug discovery to identify those regions in chemical space that contain molecules of oral druglike quality that are likely to be biologically active. Virtual screening has the unique capability of not only searching the small fraction of chemical space occupied by compounds in existing screening collections but also exploring new and so far undiscovered regions (Figure 1.1). The challenge for the future is to better define and systematically explore those promising areas in chemical space.

Figure 1.1 Regions of biologically and medicinally relevant chemical space within the continuum of chemical space. Only a small portion of chemical space has been sampled by existing compound collections, which led to the discovery of drugs (A). Virtual screening has the unique opportunity to expand into unexplored chemical space to find new pockets of space where drugs are likely to be discovered (B).

1.2 Concepts of Chemical Space

Despite the fact that the term chemical space has received widespread attention in drug discovery, only few concrete definitions have been proposed. Lipinski suggested that chemical space “can be viewed as being analogous to the cosmological universe in its vastness, with chemical compounds populating space instead of stars” [1]. More concrete, chemical space can be defined as the entire collection of all meaningful chemical compounds, typically restricted to small organic molecules [2]. To navigate through the vastness of chemical space, compounds can be mapped onto the coordinates of a multidimensional descriptor space. Each dimension represents various properties describing the molecules, such as physicochemical or topological properties, molecular fingerprints, or similarity to a given reference compound [3]. Depending on the particular descriptor and property set used for defining a chemical space, the representation of compounds in this chemical space varies. Thus, the relative distribution of molecules within the chemical space and the relationship between them strongly depend on the chosen descriptor set. The consequence of this is that changes in chemical representation of molecules are likely to result in changes in their neighborhood relationship. This aspect is important to keep in mind when it comes to measuring diversity or similarity within a set of molecules.

How vast is chemical space? Various estimates of the size of chemical space have been proposed. The number of all possible, small organic compounds ranges anywhere from 1018 to 10180 molecules [4]. The first attempt to systematically enumerate all molecules of up to 13 heavy atoms applying basic chemical feasibility rules resulted in less than 109 structures [5]. However, with every additional heavy atom the number of possible structures grows exponentially due to the combinatorial explosion of enumeration. Thus, it is estimated that with less than 30 heavy atoms more than 1063 molecules with a molecular weight of less than 500 can be generated, predicted to be stable at room temperature and stable toward oxygen and water [6]. Compared to the estimated number of atoms in the entire observable universe (1080), it seems that for all practical purposes chemical space is infinite and any attempt to fully capture it even with computational methods appears to be futile. Even more, in contrast to the number of compounds in a typical screening collection of large pharmaceutical companies (106) it becomes clearly obvious that only a tiny fraction of chemical space is examined.

One might ask why hit identification in drug discovery is successful, despite the fact that only a very limited set of compounds within the entire chemical space is being probed. It has been hypothesized that existing screening collections are not just randomly selected from chemical space, but are already enriched with molecules that are likely to be recognized by biological targets [7]. Many synthesized compounds have been derived from natural products, metabolites, protein substrates, natural ligands, and other biogenic molecules. Hence, a certain “biogenic bias” is inherently built into existing screening libraries resulting in an increased chance of finding active hits. This observation indicates that, given the vast and infinite size of chemical space, the goal should not be to exhaustively sample the entire space but to identify those regions that contain compounds likely to be active against biological targets (biologically relevant chemical space).

Another limiting factor is that not all biologically active molecules have the desired physicochemical properties required for oral drugs. There are many aspects important for a biologically active compound to become a safe and orally administered drug, such as absorption, permeability, metabolic stability, or toxicity. The concept of druglikeness has been introduced to determine the characteristics necessary for a drug likely to be successful. Over time, this has been further extended toward leadlike criteria with more stringent rules and guidelines recommended for compounds in a screening collection (Section 1.3). It is generally assumed that molecules have an increased chance to be successfully developed into a medicine when they satisfy lead- and druglike criteria (medicinally relevant chemical space).

Unfortunately, not much is known about the size and regions of biologically and medicinally relevant chemical space. Current definitions of such relevant spaces often rely on the knowledge of existing, mostly orally administered drugs, and are limited by the chemical diversity of historical screening collections and by the biological diversity of known druggable targets. On one side, the data accumulated so far suggest that compounds active against certain target families (e.g., GPCRs, kinases, etc.) tend to cluster together in specific regions of chemical space [8]. For individual targets from those families, the relevant chemical space seems to be well defined, and the likelihood of finding drugs in these defined regions is high (Section 1.5). On the other side, there are many target classes that have been deemed as difficult or undruggable, such as certain proteases or phosphatases. Also, a fairly unresolved area in drug discovery is the identification of small molecule modulators of protein–protein interactions in biological signaling cascades [9]. It is assumed that the chemical space represented by traditional screening collections is inadequate to successfully tackle these “tough targets,” and new regions of chemical space need to be explored. Possible sources of chemical matter potentially occupying such unexplored regions of space can be derived from natural products or through emerging technologies such as diversity-oriented synthesis for generating natural product-like combinatorial libraries (Section 1.4).

1.3 Concepts of Druglikeness and Leadlikeness

It has been demonstrated that the lead development stage contributes 40% to the overall attrition rate throughout the whole drug development process, beginning from the first assay development to final registration [10]. Therefore, it is assumed that significant improvements can be realized in the early phase of lead identification and development. In-depth analysis of marketed oral drugs led to the introduction of druglikeness that defines the physicochemical properties that determine key issues of drug development, such as absorption and permeability. Lipinski's influential analysis of compounds failing to become orally administered drugs resulted in the well-known “rule of five” [11]. In short, the rule predicts that poor absorption or permeation of a drug is more likely to occur when there are more than 5 H-bond donors, 10 H-bond acceptors, the molecular weight is greater than 500, and the calculated log P is greater than 5 (Table 1.1). The concept of druglikeness has been widely accepted and embraced by scientists in drug discovery nowadays, with many variations and extensions of the original rules, and it has served its purpose well to help optimize pharmacokinetic properties of drug candidate molecules [12, 13].

Table 1.1 Comparison of properties typically used for leadlikeness and druglikeness criteria.

| Properties | Leadlikeness | Druglikeness |

| Molecular weight (MW) | ≤350 | ≤500 |

| Lipophilicity (clog P) | ≤3.0 | ≤5.0 |

| H-bond donor (sum of NH and OH) | ≤3 | ≤5 |

| H-bond acceptor (sum of N and O) | ≤8 | ≤10 |

| Polar surface area (PSA) | ≤120 Å2 | ≤150 Å2 |

| Number of rotatable bonds | ≤8 | ≤10 |

| Structural filters | Reactive groups | |

| Warhead-containing agents | ||

| Frequent hitters | ||

| Promiscuous inhibitors |

The rules defining druglikeness, however, should not necessarily be applied to lead molecules. One of the reasons is the observation that, on average, compounds in comparison to their initial leads become larger and more complex during the lead optimization phase, and the associated physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, calculated log P, etc.) increase accordingly [14, 15]. To ensure that the properties of an optimized compound remain within druglike space, the criteria for leadlikeness have been more narrowly defined to accommodate the expected growth during drug optimization (Table 1.1). Complementary to the comparison of drug and lead pairs from historical data, Hann et al. analyzed in a more theoretical approach, using a simplified ligand–receptor interaction model, how the probability of finding a hit varies with the complexity of a molecule [16]. The model shows that the probability of observing a “useful interaction event” decreases when molecules become increasingly complex. This suggests that less complex molecules, in accordance with leadlike...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Methods and Principles in Medicinal Chemistry

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Contributors

- Preface

- A Personal Foreword

- Part One: Principles

- Part Two: Challenges

- Part Three: Applications and Practical Guidelines

- Part Four: Scenarios and Case Studies: Routes to Success

- Appendix A: Software Overview

- Appendix B: Virtual Screening Application Studies

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Virtual Screening by Christoph Sotriffer, Raimund Mannhold,Hugo Kubinyi,Gerd Folkers in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.