- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Gastroenterology and Hepatology

About this book

This new title in the award-winning Lecture Notes series provides a clinically-oriented approach to the study of gastroenterology and hepatology, covering both the medical and surgical aspects of gastrointestinal practice. It explores organ-specific disorders, clinical basics, and gastrointestinal emergencies, together with a detailed self-assessment section. As part of the Lecture Notes series, this book is perfect for use as a concise textbook or revision aid.

Key features include:

- Takes a clinically-oriented approach, covering both medical and surgical aspects of gastrointestinal practice

- Includes sections devoted to the organ-specific disorders, clinical basics and gastrointestinal emergencies

- Includes a detailed self-assessment section comprising MCQs, SAQs and short and long OSCE cases

Whether you need to develop or refresh your knowledge, Gastroenterology and Hepatology Lecture Notes presents 'need to know' information for all those involved in gastrointestinal practice.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Gastroenterology and Hepatology by Anton Emmanuel, Stephen Inns, Anton Emmanuel,Stephen Inns in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Gastroenterology & Hepatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Clinical Basics

1

Approach to the patient with abdominal pain

In gastroenterological practice, patients commonly present complaining of abdominal pain. The clinician’s role is to undertake a full history and examination, in order to discern the most likely diagnosis and to plan safe and cost-effective investigation. This chapter describes an approach to this process.

History taking

Initially the approach to the patient should use open-ended questions aimed at eliciting a full description of the pain and its associated features. Useful questions include:

‘Can you describe your pain for me in more detail?’

‘Please tell me everything you can about the pain you have and anything you think might be associated with it.’

‘Please tell me more about the pain you experience and how it affects you.’

Only following a full description of the pain by the patient should the history taker ask closed questions designed to complete the picture.

In taking the history it is essential to elucidate the presence of warning or ‘alarm’ features (Box 1.1). These are indicators that increase the likelihood that an organic condition underlies the pain. The alarm features guide further investigation.

Historical features that it is important to elicit include the following.

Onset

- Gradual or sudden? Pain of acute onset may result from an acute vascular event, obstruction of a viscus or infection. Pain resulting from chronic inflammatory processes and functional causes are more likely to be of gradual onset.

Frequency and duration

- Colicky pain (which progresses and remits in a crescendo–decrescendo pattern)? Usually related to a viscus (e.g. intestinal renal and biliary colic), whereas constant intermittent pain may relate to solid organs (Box 1.2).

- How long has the pain been a problem? Pain that has been present for weeks is unlikely to have an acutely threatening illness underlying it and pain of very longstanding duration is unlikely to be related to malignant pathology.

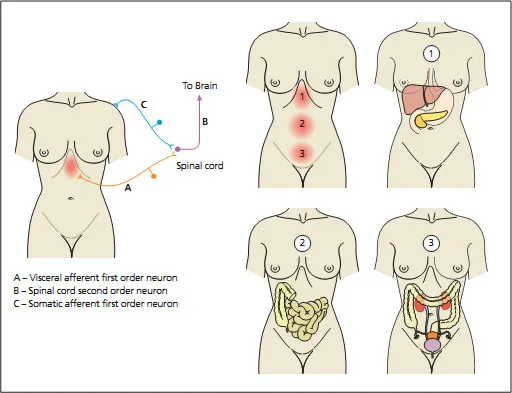

Location: radiation or referral (Figure 1.1)

- Poorly localised? Usually related to a viscus (e.g. intestinal, renal and biliary colic).

- Located to epigastrium? Disorders related to the liver, pancreas, stomach and proximal small bowel (from the embryological foregut).

- Located centrally? Disorders related to the small intestine and proximal colon (from the embryological midgut).

Box 1.1 Alarm features precluding a diagnosis of irritible bowel syndrome (IBS).

History

- Weight loss

- Older age

- Nocturnal wakening

- Family history of cancer or IBD

Examination

- Abnormal examination

- Fever

Investigations

- Positive faecal occult blood

- Anaemia

- Leucocytosis

- Elevated ESR or CRP

- Abnormal biochemistry

- Located to suprapubic area? Disorders related to the colon, renal tract and female reproductive organs (from the embryological hindgut).

Radiation of pain may be useful in localizing the origin of the pain. For example, renal colic commonly radiates from the flank to the groin and pancreatic pain through to the back.

Referred pain occurs as a result of visceral afferent neurons converging with somatic afferent neurons in the spinal cord and sharing second order neurons. The brain then interprets the transmitted pain signal to be somatic in nature and localises it to the origin of the somatic afferent, distant from the visceral source.

Character and nature

- Dull, crampy, burning or gnawing? Visceral pain: related to internal organs and the visceral peritoneum.

- Sharp, pricking? Somatic pain: originates from the abdominal wall or parietal peritoneum (Figure 1.1).

One process can cause both features, the classical example being appendicitis which starts with a poorly localised central abdominal aching visceral pain; as the appendix becomes more inflamed and irritates the parietal peritoneum, it

Box 1.2 Characteristic causes of different patterns of abdominal pain.

Chronic intermittent pain

- Mechanical:

- Intermittent intestinal obstruction (hernia, intussusception, adhesions, volvulus)

- Gallstones

- Ampullary stenosis

- Inflammatory:

- Inflammatory bowel disease

- Endometriosis/endometritis

- Acute relapsing pancreatitis

- Familial Mediterranean fever

- Neurological and metabolic:

- Porphyria

- Abdominal epilepsy

- Diabetic radiculopathy

- Nerve root compression or entrapment

- Uraemia

- Miscellaneous:

- Irritable bowel syndrome

- Non-ulcer dyspepsia

- Chronic mesenteric ischaemia

Chronic constant pain

- Malignancy (primary or metastatic)

- Abscess

- Chronic pancreatitis

- Psychiatric (depression, somatoform disorder)

- Functional abdominal pain

progresses to sharp somatic-type pain localised to the right lower quadrant.

Exacerbating and relieving features

Patients should be asked if there are any factors that ‘bring the pain on or make it worse’ and conversely ‘make the pain better’. Specifically:

- Any dietary features, including particular foods or the timing of meals? Patients with chronic abdominal pain frequently attempt dietary manipulation to treat the pain. Pain consistently developing soon after a meal, particularly when associated with upper abdominal bloating and nausea or vomiting, may indicate gastric or small intestinal pathology or sensitivity.

Figure 1.1 Location of pain in relation to organic pathology. A, Visceral afferent first-order neuron; B, spinal cord second-order neuron; C, somatic afferent first-order neuron.

- Relief of low abdominal pain by the passage of flatus or stool? This indicates rectal pathology or increased rectal sensitivity.

- The effect of different forms of analgesia or antispasmodic used may give clues as to the aetiology of the pain. Simple analgesics such as paracetamol may be more effective in treating musculoskeletal or solid organ pain, whereas antispasmodics such as hyoscine butylbromide (Buscopan) or mebeverine may be more beneficial in treating pain related to hollow organs.

- Pain associated with twisting or bending? More likely related to the abdominal wall than intra-abdominal structures.

- Pain severity may be affected by stress in functional disorders, but increasing evidence shows that psychological stress also plays a role in the mediation of organic disease, such as inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

Any associated symptoms?

The presence of associated symptoms may be instrumental in localising the origin of the pain.

- Relationship to bowel habit: frequency, consistency, urgency, blood, mucus and any association of changes in the bowel habit with the pain is important. Fluctuation in the pain associated with changes in bowel habit is indicative of a colonic process and is typical of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS).

- Vomiting or upper abdominal distension? Suggestive of small bowel obstruction or ileus.

- Haematuria? Indicates renal colic.

- Palpable lump in the area of tenderness? Suggests an inflammatory mass related to transmural inflammation of a viscus, but may simply be related to colonic loading of faeces.

Examination technique

The physical examination begins with a careful general inspection.

- Does the patient look unwell? Obvious weight loss or cachexia is an indicator of malabsorption or undernourishment.

- Is the patient comfortable? If in acute pain, are they adopting a position to ease the pain? The patient lying stock still in bed with obvious severe pain may well have peritonitis, whereas a patient moving about the bed, unable to get comfortable, is more likely to have visceral pain such as obstruction of a viscus.

- Observation of the skin may demonstrate jaundice, pallor associated with anaemia, erythema ab igne (reticular erythematous hyperpigmentation caused by repeated skin exposure to moderate heat used to relieve pain), or specific extraintestinal manifestations of disease (Table 1.1). Leg swelling may be an indicator of decreased blood albumin related to liver disease or malnutrition.

- Observe the abdomen for visible abdominal distension (caused by either ascites or distension of viscus by gas or fluid).

- Vital signs, including the temperature, should be noted.

- Examination of the hands may reveal clues to intra-abdominal disease. Clubbing may be related to chronic liver disease, IBD or other extra-abdominal disease with intra-abdominal consequences. Pale palmar creases may be associated with anaemia. Palmar erythema, asterixis, Dupytren’s contractures and spider naevi on the arms may be seen in chronic liver disease.

- Inspection of the face may reveal conjunctival pallor in anaemia, scleral yellow in jaundice, periorbital arcus senilis indicating hypercholesterolaemia and an increased risk of vascular disease or pancreatitis.

- Careful cardiac and respiratory examinations may reveal abnormalities associated with intra-abdominal disease. For example, peripheral vascular disease may indicate a patient is at risk for intestinal ischaemia; congestive heart failure is associated with congestion of the liver, the production of ascites and gut oedema; and pain from cardiac ischaemia or pleuritis in lower lobe pneumonia may refer to the abdomen.

- Examination of the GI system per se begins with careful inspection of the mouth with the aid of a torch and tongue depressor. The presence of numerous or large mouth ulcers or marked swelling of the lips may be associated with IBD. Angular stomatitis occurs in iron deficiency. Glossitis may develop in association with vitamin B12 deficiency caused by malabsorption.

Table 1.1 Extraintestinal manifestations of hepatogastrointestinal diseases.

| Disease | Dermatological | Musculoskeletal |

| Inflammatory bowel disease: | ||

| • Crohn’s disease | Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum | Axial arthritis more common |

| • Ulcerative colitis | Erythema nodosum, pyoderma gangrenosum | Axial and peripheral arthritis similar in frequency |

| Enteric infections (Shigella, Salmonella, Yersinia, Campylobacter) | Keratoderma blennorrhagica | Reactive arthritis |

| Malabsorption syndromes: | ||

| • Coeliac sprue | Dermatitis herpetiformis | Polyarthralgia |

| Viral hepatitis: | ||

| • Hepatitis B | Jaundice (hepatitis), livedo reticularis, skin ulcers (vasculitis) | Prodrome that includes arthralgias; mononeuritis multiplex |

| • Hepatitis C | Jaundice (hepatitis), palpable purpura | Can develop positive rheumatoid factor |

| Henoch–Schönlein purpura | Palpable purpura over buttocks and lower extremities | Arthralgias |

- Examination of the thyroid is followed by examination of the neck and axilla for lymphadenophathy.

- Car...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title

- Copyright

- Preface

- Part I: Clinical Basics

- Part II: Gastrointestinal Emergencies

- Part III: Regional Gastroenterology

- Part IV: Study Aids and Revision

- Part V: Self-Assessment

- Index