![]()

CHAPTER 1

Sudden cardiac death

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) – also known as sudden cardiac arrest (SCA) – has been defined as the unexpected natural death from a cardiac cause within a short time period from the onset of symptoms in a person without any prior condition that would appear fatal.1 SCD has been described as an ‘electrical accident of the heart,’ in that SCD is a complex condition which requires the patient to have certain preexisting conditions and then certain triggering events in order to occur. SCD is responsible for about 400 000 deaths a year in the US.2 Despite our growing knowledge about the mechanisms and markers of this killer disease, SCD remains difficult to treat because the first symptom of SCD is often death.

Many risk factors have been identified for SCD. About 80% of those who suffer SCD have coronary artery disease (CAD), and the incidence of SCD parallels the incidence of CAD (men have CAD and SCD more often than women do, for example). One distinction is that while both CAD and cardiacrelated death increase with age, sudden cardiac death decreases with age versus non sudden cardiac death (NSCD). Older individuals are more likely to experience NSCD than SCD. The peaks of incidence of SCD occur in infants (birth to 6 months) and again between ages 45 and 75 years.1

Several risk factors have been identified for SCD. Some of them are the usual risk factors for any form of heart disease: smoking, inactivity, obesity, advancing age, hypertension, elevated serum cholesterol, and glucose intolerance. Anatomical abnormalities have been associated with SCD. For instance, acute changes in coronary plaque morphology (thrombus or plaque disruption) occur in the majority of cases of SCD cases; about half of all SCD victims have myocardial scars or active coronary lesions.3 For people with advanced heart failure, a non sustained ventricular arrhythmia was found in one study to be an independent predictor of SCD.4 One report bolstered the popular belief that emotional distress can bring on SCD, in that it was found that the incidence of SCD spiked in Los Angeles right after the Northridge earthquake in 1994.5 Other risk factors include the presence of complex ventricular arrhythmias, a previous myocardial infarction (MI) (particularly post-MI patients with ventricular arrhythmias) and compromised left ventricular systolic function. A low left ventricular ejection fraction is a risk factor that affects people with and without CAD. SCD survivors with a left ventricular ejection fraction < 30% have a 30% risk of dying of SCD in the next 3 years, even if they are not inducible in an electrophysiology study. If these patients are inducible to a ventricular arrhythmia despite drugs or empirical amiodarone, the risk can climb to as high as 50%!6

SCD typically involves a malignant arrhythmia. In order for SCD to occur, a triggering event must occur which then has to be sustained by the substrate long enough to provoke the lethal rhythm disorder. The vast majority of SCD cases occur in people with anatomical abnormalities of the myocardium, the coronary arteries, or the cardiac nerves. Typical substrates are anatomical (scars from previous MIs, for example) but electrophysiologists also recognize functional substrates (such as those created by hypokalemia or certain drugs). By far the most common structural abnormalities are caused by CAD and its aftermath, the heart attack or MI. Cardiomyopathy is estimated to be the substrate for about 10% of SCD cases in adults.7 Many people possess the substrates or conditions that make an SCD possible, yet they will never experience the disease. This is because SCD requires a triggering event which not only must occur, it must be sustained on the substrate long enough to develop into a deadly arrhythmia.

Reentry is by far the most common electrophysiologic mechanism involved in SCD. Reentry occurs when a natural electrical impulse from the heart gets ‘trapped’ in a circular electrical pathway in such a way that the impulse keeps re-entering the circuit, faster and faster, provoking a disordered and rapidly accelerating cardiac arrhythmia.

If the human heart were electrically homogenous, reentry and SCD could not occur. The healthy heart has electrical heterogeneity, which means that at any given moment, some cardiac cells are conducting while others are resting. At any point in time, different areas of the healthy heart are at different stages in the electrical cycle. To understand this better, it is useful to review the basics of cellular depolarization, repolarization, and membrane potential.

Action potential

All cells in the human body are covered with a semipermeable membrane that selectively allows some materials to penetrate into the cell while filtering out others. For cardiac cells, the membrane allows charged particles (ions) to flow in and out of the cell at specific times. By regulating the inflow and outflow of ions (electrical charge), cardiac cells are capable of generating and conducting electricity.

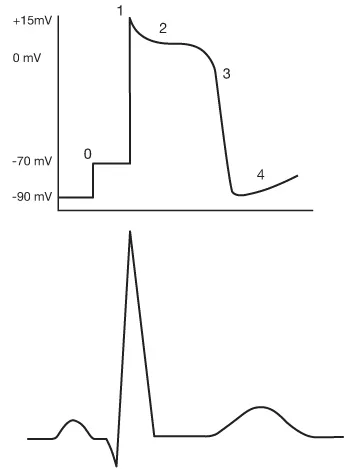

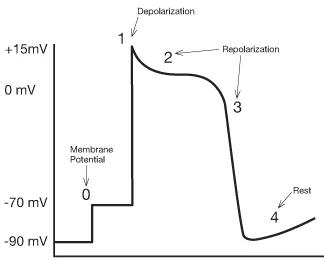

Even at rest, a cell in the heart has a certain number of ions within it that give it what scientists would call an ‘electrical potential.’ Electrophysiologists refer to this measurable electrical charge as ‘membrane potential,’ in that it is the electrical potential contained within the cardiac cell’s membrane. The action potential describes five phases (numbered 0 through 4) that show how a cardiac cell goes from resting membrane potential (about –90 millivolts or thousandths of a volt) through depolarization, repolarization, and back to resting membrane potential (see Fig. 1.1).

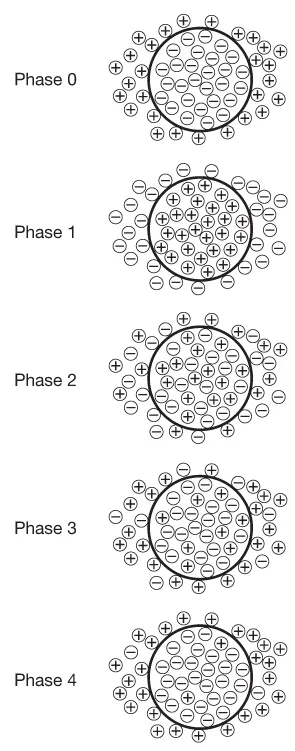

In its resting state (phase 0), a cardiac cell contains a large quantity of negative ions (anions). Positive ions (cations) outside the cell are blocked from entering by the cell’s membrane but they line up around the cardiac cell, attracted to the negatively charged particles within. It almost appears as if the inside of the heart cell was a negative pole and the immediate exterior of the cardiac cell was the positive pole. From this situation where opposites attract, the term ‘polarization’ is given. The charges polarize negative against positive. The membrane potential phases go from this polarized state (resting membrane potential) to depolarization, then repolarization, and back to the polarized state (resting membrane potential) (see Fig. 1.2).

When an electrical impulse reaches a cardiac cell, the cardiac cell membrane becomes permeable to positively charged sodium ions. Attracted by the negative pole within the cell, sodium ions rush into the cell until the interior of the cell is less negative and the exterior immediately around the cell’s membrane is less positive. This shift decreases the cell’s resting membrane potential to the point where fast sodium channels open in the cell membrane. Fast sodium channels are just like they sound; they allow a very rapid influx of positively charged sodium ions into the cell. As a result, the interior of the cell becomes positive and the exterior around the cell becomes negative. This phase – where polarization is reversed – is called depolarization.

The main physiological effect of cardiac depolarization is that the heart cells contract. That’s why electrophysiologists frequently refer to the squeezing or pumping action of the heart muscle as ‘depolarization,’ since that best describes what is going on in the heart’s cells. At the cellular level, cardiac cells are becoming positively charged on the interior, negatively charged on the exterior – and this results in a heart beat.

The very process of contraction begins the next phase of the membrane potential, in that the positively charged sodium ions start to leave the inside of the cardiac cell when the cell contracts. Electrophysiologists call this process of getting back to the original resting membrane potential ‘repolarization,’ and it is characterized physiologically by the heart returning to a relaxed or resting state. At the cellular level, the positive ions flow out while negative ions flow back in using sodium as well as calcium and potassium channels. It is impossible for the cardiac cell to depolarize again until it has com–pleted all three phases involved in repolarization; during phases 1–3, the cardiac cell is refractory.

The final phase of the action potential (phase 4) might best be viewed as a brief moment of rest. At the cellular level, there is very little activity going on, with only a few ions crossing the cell membrane either way (see Fig. 1.3).

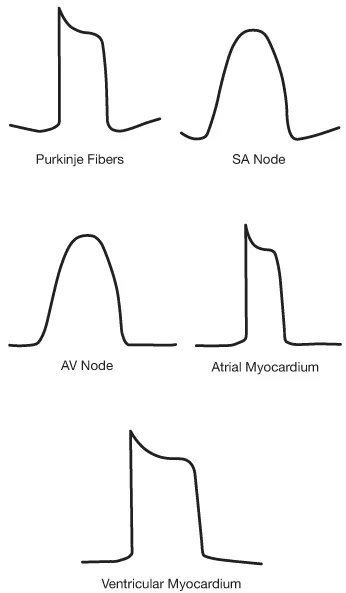

The morphology of the action potential varies depending on the type of cardiac cell involved. Phase 0 shows how quickly the cell depolarizes, while phases 1–3 show how long the refractory period is. The action potentials from some main locations in the heart show that cardiac cells are specialized in terms of how fast they depolarize and how long they remain refractory (not able to depolarize) (see Fig. 1.4).

Automaticity

Automaticity is the heart’s ability to spontaneously generate electricity. The specialized cells in the heart's sinoatrial (SA) node possess this remarkable property. The SA node is sometimes called the heart’s ‘natural pacemaker’ for its ability to keep the healthy heart beating properly. Other myocardial cells possess automaticity and may spontaneously deliver an electrical output. In fact, many regions of the heart, including the atrioventricular (AV) node and even ventricular tissue, possess enough automaticity to ‘fire’ an electrical output. However, the heart’s conduction system requires the electrical output to travel a specific path through the heart. At any given moment, the electrical pathway can only accommodate one output, and the heart works on a first-come, first-served principle. (In the cardiac conduction system, the fastest impulse wins.) The first output that gets on track is the one that travels. Other cells might generate an electrical output based on the principle of automaticity, but the pathway they will travel is refractory (not subject to depolarization because it is in phase 1, 2, or 3 of the action potential) and thus, the electricity will have no effect on the cells.

Automaticity and triggered automaticity are two of the three main causes of tachycardia, although altogether they account for only about 10% of all tachycardias. Automaticity involves abnormal acceleration of phase 4 of the action potential, causing the heart to launch into another depolarization too quickly. Its cause is increased activity across the heart’s membrane in phase 4, usually involving a mechanism known as the sodium–potassium pump. As such, automaticity and triggered automaticity tachycardias have metabolic or cellular causes, and since they are not caused electrically, they do not respond to defibrillation. In fact, tachycardias caused by automaticity cannot be reproduced in the electrophysiology lab. The main causes of automatic tachycardias are thought to be ischemia (diseased heart tissue caused by CAD), electrolyte imbalances, acid/base imbalances, drug toxicity, and myopathy (muscle disorder).

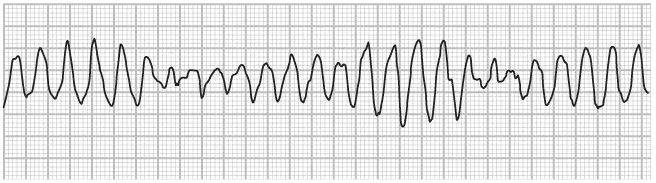

It is often possible to observe the locations and types of cardiac disturbances by viewing variations in the action potential. Triggered automaticity looks a lot like reentry tachycardia on the action potential. It occurs when something triggers an automaticitytype tachycardia. A typical trigger might be a bradycardic pause or a catecholamine imbalance. This trigger accelerates phase 4 of the action potential, causing the heart to launch the next depolarization too quickly, resulting in an accelerating heart rate. A common example of triggered automaticity is the torsades-de-pointes type of tachycardia. Torsades-de-pointes (twisting points) takes its name from the French and describes the twisting or turning action the ECG seems to show (see Fig. 1.5).

Reentry

By far the most common mechanism for tachycardias anywhere in the heart is reentry, responsible for about 90% of all tachycardias. Although common, reentry is a complex mechanism which requires several specific conditions to be met before it can occur.

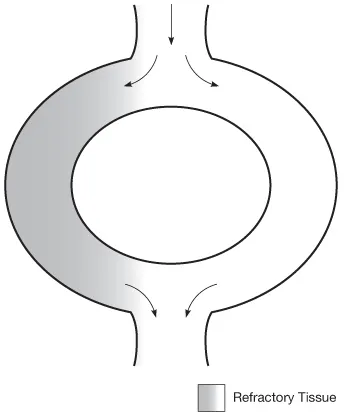

Reentry tachycardia first requires a bypass tract. The conduction pathway through the heart (from SA node over the atria to the AV node then out across the ventricles) is ideally a series of relatively straightforward unidirectional pathways from origin to termination. An impulse entering the pathway travels down through the cells, creating a cascade effect of depolarization and repolarization. Electrical impulses that enter the pathway after the initial impulse may still travel, but they encounter only refractory cells and cause no depolarization. A bypass tract occurs when the conduction pathway forms a branch that splits but then reconnects. As a result impulses traveling down the pathway may go down one side or the other, but will eventually regroup at the end (see Fig. 1.6).

For reentry to occur, this bypass tract must have a fast path and a slow path, that is, the two arms of the bypass tract must be electrically heterogeneous, that is, they must conduct electricity at different speeds. This, in turn, means that the two pathways will have different refractory periods. Impulses will travel more quickly through one path than the other, and one pathway can be refractory (not subject to depolarization) at the same time as the other pathway is depolarizing.

Finally, a reentry tachycardia requires some sort of triggering e...