![]()

PART I

PREPARATION AND STRATEGY

![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Innovation Paradox

The problem is simple, and indeed, paradoxical. Research shows people like new products and services. They want them. And, indeed, they go out of their way to try to find them. Yet companies are truly terrible at providing the new products and services that meet their customers’ needs.

In the 1980s, research showed nine out of 10 new products failed. Some 30 years later, nothing has changed. Our research—confirmed by other firms—shows that nine out of 10 new products still fail today.

Moreover, when you look deeper—and we will walk you through our proprietary data in a minute—you actually find a second paradox within the original paradox: companies know introducing new products and services successfully is something they need to do to ensure a healthy future. And yet they readily concede that they are not devoting sufficient resources to make it happen. And at the risk of having this sound like the business equivalent of a matryoshka (those Russian dolls that nest inside one another) the reality is that there is even a third paradox within the second paradox within the initial paradox: Firms are aware that they have a problem—they openly admit that are not very good at introducing new products and services—but they have made remarkably little effort to improve their batting averages—apparently convinced that introducing new products is inherently a hit or miss process.

When you add all this up, it is easy to understand why there is a huge gap between customers’ desires for new products and the ability for companies to deliver them. We call this the innovation paradox. And the situation is far worse than most senior managers and marketing executives believe.

A Look at the Numbers

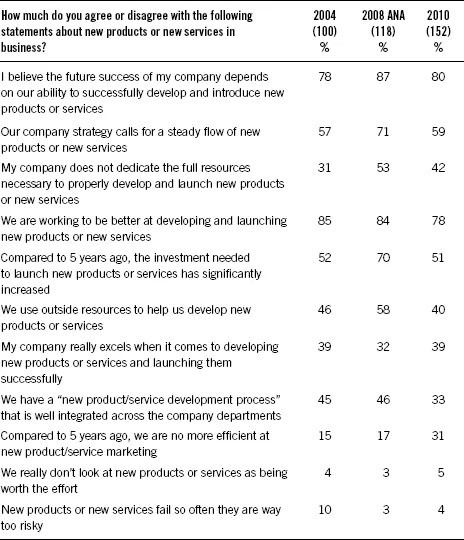

Let’s spend a couple of minutes and look at just how severe the problem is by reviewing the research we have at our fingertips. In 2004, 2008, and again in 2010, we surveyed a representative sample of the nation’s best companies. In the first survey we talked to marketers at firms of all sizes. In the second survey we limited our questions to companies that are members of the Association of National Advertisers (an organization of some 300 companies of bigger firms with a total of more than 8,000 brands). And in the third, we went back out to a representative sample of the marketing decision makers. In all three instances, almost half the people we talked to were in senior positions like director of marketing or above. Here’s what we found:

As the first line in Table 1.1 shows, about 80 percent of companies say their futures depend on introducing new products. That fact is not surprising. It is commonplace to hear a CEO say something like, “five years from now, we expect a third of our revenues to come from products that don’t exist today.”

Table 1.1 What Executives Think about Their New Product Prowess

And it is not just the CEO who is preaching about the importance of new products. Wall Street is as well. This excerpt from the Harvard Business Review:

We added the emphasis in italics. But there isn’t a single senior manager we know who would disagree with this statement. You see proof of it in the second line of Table 1.1, where the majority of executives agree with the statement “our company strategy calls for a steady flow of new products.” What should follow from lines one and two is that companies are pouring tons of money into the new product development process. But that is simply not the case in practice, as you can see from line three of Table 1.1. When asked if they agreed with the following statement: “my company does not dedicate the full resources necessary to properly develop and launch new products,” more than half (53 percent) of ANA members agreed.

Theoretically, that wouldn’t necessarily be a huge problem. If the cost of new product introductions were falling, then a lack of resources is something that could be overcome by having really smart people—those with extensive experience in handling new product introductions—work full-time on getting new products into the customers’ hands. They’d come up with oodles of products, introduce them all into the marketplace, and something would be bound to resonate with consumers.

Theoretically that could work. But the reality is, as line four in Table 1.1 shows, the cost of new product introductions is going up, not down. The majority of people said the cost of new product introductions is higher than it was five years ago. So the “let’s-try-everything-and-see-what-resonates” approach is not going to work. The fact that it is more and more expensive to introduce new products—meaning the cost of new product failure is also climbing—is daunting. And the situation gets even more disheartening when we get to the question of expertise.

The cost of new product introductions climbs steadily higher. That makes bungling an introduction not only embarrassing—but increasingly expensive.

Companies understand what follows from all this and you see the depressing results in line seven: only about a third of executives believe their company “excels” at introducing new products. But, there is hope in that at least half of the people surveyed understand one of their problems in bringing new products successfully to market: They don’t have a fully integrated process for doing so.

They have a process for evaluating acquisitions. They have a process for reviewing people for raises and promotions. They even have a process for ordering paper clips, yet, as line seven in Table 1.1 tells us, they don’t have a process for something that is vital to their company’s future—handling new product introductions.

And Then It Really Falls Apart

What is seemingly clear from everything we have just talked about is that companies recognize that they need to introduce new products successfully. And yet at the same time they concede that they are not as good at the process of introducing new products as they should be. But we say “seemingly” because of the way the executives answered the questions in Table 1.1.

The Executive’s Reactions

The overwhelmingly positive response to the question “we are working to be better at developing and launching new products,” can be read two ways. Everybody says they’re doing that but it also could just be an acknowledgment that senior executives recognize that they have a problem when it comes to new product introductions and they are taking steps to improve the people and processes required to increase their success rate. It could be read that way. But, it also could be whistling past the graveyard. Who wants to admit publicly that they have a problem and aren’t doing anything about it? Of course you are going to say that you are working on fixing a problem—even if you are not really doing very much at all.

And spending an extra minute with the numbers confirms the whistling past the graveyard theory. Executives concede they don’t have a well integrated “new product/service development process and admit they do “not dedicate the full resources necessary to properly develop and launch new products or new services.”

By inference, line 11 supports the whistling past the graveyard theory. Senior executives know they are not good at introducing new products (line seven), and they told us that a key reason for that is that the people they rely on to introduce the new products—brand and product managers—don’t have the requisite skill (line five). And yet, in 2010, only four in 10 companies brought in outside resources to help.

Executives are saying, in essence, “we are going to continue to work on new products ourselves—even though:

a. we know we are not very good at it, (and as we discuss later in this chapter, the “we” includes marketers themselves);

b. we have a terrible track record when it comes to introducing new products successfully, and;

c. we really don’t have a clue what the problem is so that we can improve our performance.”

To be kind, the executives’ reactions do not make sense. Can you imagine any CEO (who wants to keep his job) saying these sorts of things when it comes to business process improvement; or how the finance department should be run; or how they should go about hiring better employees? They wouldn’t dare to . . . so why should new product introductions be any different?

Marketers: One of the Enemies Within

In further looking at the numbers, we noticed marketers poorly graded their company’s ability to introduce new products. That got us to wondering how good they thought they themselves were at it. Their answer: not very.

We surveyed marketers from the same two groups we talked about earlier and said, “please rate yourself in these three main actions associated with new product marketing:

- Introducing new products;

- Developing and introducing line extensions;

- And repositioning or relaunching a product.”

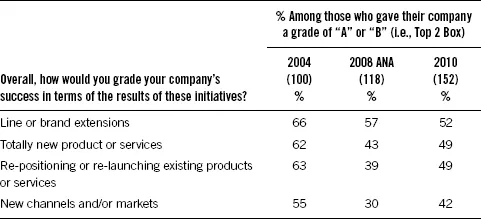

We asked them to give themselves an A if they were extremely good at an activity; a B if they were good; a C if they thought they were average; a D if they thought they were poor at something; and an F if they flat out stunk in a particular category. Table 1.2 shows how they responded.

Table 1.2 Grading of Strategy, Planning, and Execution

As you can see, the vast majority of marketers gave themselves extremely low marks. For example, if you look at the first column—introducing new products—you see that less than half of the respondents (49 percent) gave themselves an A or B. In the third column—introducing products into new channels or markets—the scores were just as bad.

In fact, the second column—introducing line or brand extensions—is the only place where there were more As and Bs than there were Cs, Ds, and Fs and it wasn’t by much—just 52 percent gave themselves good marks.

Where Do We Go from Here?

So where do these numbers leave us? What do they all mean? Well, for one thing, they mean the New Product Paradox we described at the beginning of this chapter is real. Customers want new products, and many companies are extremely bad at providing them. But we also know something else from the survey results. Companies are just starting to say—reluctantly—in public that they have a problem and are committed to solving it.

Jeffery Immelt, chairman and CEO of GE, in a recent address to shareholders, talked about the need for an “innovation imperative” at his company, whose stock has been essentially flat for years. Steve Ballmer, CEO of Microsoft, said in a recent interview that he believes innovation is the only way his company can satisfy customers and stay ahead of the competition. And William Ford, Jr., chairman of Ford Motor Co., says that from now on, innovation will be the compass by which his company sets its strategy.

Creating new products and services will be at the heart of those innovation initiatives and that, of course, takes us full circle: people want new products and services, and companies want to do a better job of providing them. The problem is they don’t know how. And that is where we come in.

People want new products and services, and companies want to do a better job of providing them. That makes the New Product Paradox that much more frustrating.

A Unique Process

Before we start talking...