![]()

Chapter 1

Spotting Bubbles

With the bursting of the U.S. housing and global financial bubbles in 2007–2008, it was inescapably clear that they were indeed bubbles. Earlier, few had agreed with me that the explosive growth and gigantic financial leverage in these two areas destined them for collapse.

Of course, if the majority doubted the sustainability of a rapidly expanding economic sector, a bubble in it would never develop. Indeed, at its peak of expansion, a bubble appears the most credible and most likely to continue to enlarge since the greatest number have invested in it and fervently hope for its continuation.

But they are then enveloped by the “willful suspension of disbelief,” which constitutes not the poetic faith to which Samuel Taylor Coleridge applied the term, but the essence of investor irrationality at bubble tops. And at that point, there are no more gullible investors left to keep expanding the bubble. My good friend and retired senior investment adviser at Merrill Lynch, Bob Farrell, the dean of Wall Street technical analysts, taught me decades ago that a speculative market peak is formed when everyone who can be sucked in has been sucked in. So there are no more potential buyers left, but lots of potential sellers.

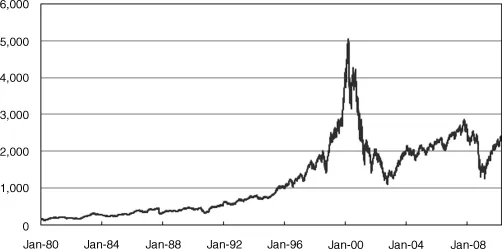

I make a practice of spotting economic and financial bubbles and then predicting their demise. This isn't easy because there always is some fundamental logic behind them. Bubbles aren't pure fluff, but initially well-founded activities that just get carried to irrational extremes. And, of course, every bubble is different, with a fresh and plausible explanation for its endless expansion. Also, there are so many intelligent and otherwise calm people who are telling the world that the prices of tulip bulbs or houses will soar forever. And how do you think I felt as a professional investor in the late 1990s when I saw the dot-com boom as a huge bubble waiting to burst? (See Figure 1.1.) My attempts to sell those stocks short as they continued to climb were frustrating, to say the least. My angst was even more intense at cocktail parties when amateur investors would revel over the new issues they'd bought and seen leap 5 or 10 times in price the first day of trading.

To see bubbles for what they are and predict their demise with unpleasant consequences, you also have to be willing to see negative sides of the economy. That goes against the grain of most Americans, who are eternal optimists; even more so, investors and especially spokesmen for big banks, brokers, and mutual funds, as well as the media who are paid to be upbeat. Back in 2006–2007, when I forecast that the subprime slime, as I dubbed it, would spread to the rest of housing, then to financial markets, and ultimately precipitate the worst recession since the 1930s, I was regularly chastised by the bulls during TV appearances. Some were downright insulting, deprecating, and thoroughly unprofessional.

Bubbles Last Longer than Expected

It's also true that bubbles tend to expand more and last longer than I and other skeptics expect. That's because they have entered the realm of irrationality that knows no bounds, while I'm trying to examine them with rational analysis. Furthermore, I have a bias toward forecasting a sooner rather than a later collapse of a bubble.

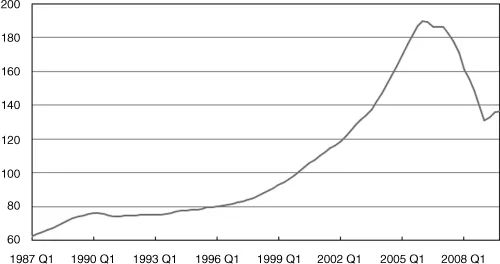

Suppose that in January 2006, I told you, as I wrote in my monthly Insight newsletter back then, that “evidence of the housing bubble's demise is mounting” and that a 20 percent decline in prices nationwide “is not a wild forecast, and may be optimistic.” And I went on to say, as I wrote at the time, that “a severe housing bust will be detrimental to the earnings and stock prices of homebuilders, building materials producers, mortgage and subprime lenders, and related entities like Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.”

Your reaction might well have been, “Wow! That's scary! When do you think the bubble will break?” I might have replied, “It may be about to break, but it could last another several years, considering the loose lending practices, low interest rates, securitization of mortgages, and expectations of ever-rising house prices that are feeding it.” Or I might have said, “I think we're right at the peak now.” In fact, house prices did peak in the first quarter of 2006 (see Figure 1.2), but I had no way of knowing that at the time, and forecasting accuracy isn't my point here. Rather, it's the fact that putting an immediacy to my forecast is much more likely to get your attention and spur you to act on it than if I place the catastrophe in the distant and indeterminate future.

Great Calls

Despite these handicaps, I'm zealous to spot bubbles because they provide excellent opportunities for great calls, which I define as having three components. First, a great call has to be important. An accurate forecast of next month's payroll employment doesn't make the cut because later revisions are likely to change the number considerably, and several more months of data would be necessary to confirm any change in trend. By contrast, my forecast in early 1973 that a massive inventory-building was taking place and would collapse into the (then) deepest recession since the 1930s obviously was an important forecast.

Second, a great call needs to be nonconsensus, as my forecast in 1973 certainly was. Almost every other forecaster thought that global shortages of almost everything were driving the economy and would last indefinitely, as opposed to an unsustainable inventory-building spree. Of course, being in the minority does subject you to the slings and arrows of the numerous doubters that constitute the consensus. But then a great call wouldn't be great unless it bucked the majority in a major way. By definition, it's a forecast that few believe until it has become a reality.

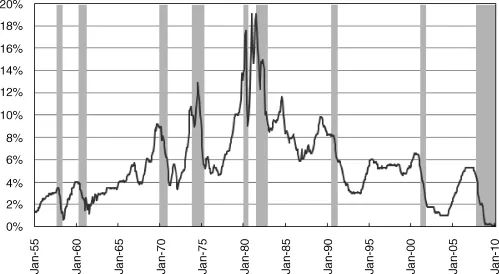

Third, a great call must unfold for the reasons stipulated ahead of time by the caller, not through dumb luck or being right for the wrong reasons. In 2007, some thought that residential subprime adjustable rate mortgages (ARMs) would collapse when those rates reset to higher levels than mortgagors could afford, not because declining house prices would wipe out the slender equity of those marginal homeowners, as I correctly forecast. The ARM rate resets had little effect because of the dramatic drop in short-term interest rates instituted by the Federal Reserve Bank (see Figure 1.3) before those resets took place.

Lucky Seven

I've made seven great calls in my economic forecasting career, which started in 1963 when I joined Standard Oil of New Jersey (now Exxon Mobil) as an economist, fresh from Stanford's PhD program. I'll discuss them shortly, and you'll see that most of them were forecasts of bubbles’ demises. But first, I'll note that those seven great calls work out to one every 6.7 years on average. Opportunities to make these significant forecasts don't occur very often, and when they do, you have to recognize them and make the correct forecast at the proper time.

Still, I think it's fair to say that my record in making great calls is far, far better than most forecasters since the vast majority seldom stray far from the consensus. There's safety in the herd, and if the boss is thinking about firing an economist or strategist for missing a great call, well, the replacement he's considering probably also missed it. Furthermore, most forecasters would rather go wrong in the good company of their peers than risk being a laughingstock for a far-out forecast that didn't pan out. In contrast, I'm uncomfortable in the herd and stimulated when my forecast is in a tiny minority. Maybe that's why I'm no longer with big firms, but instead run my own shop. Of course, my approach can be embarrassing, especially to my wife at times. We'll go to a cocktail party and someone will remark, “Oh, what a beautiful yellow moon tonight!” I've been known to reply, “Are you sure it isn't green?”

Also, the consensus has ingenious ways to deal with missed great calls. In July 2007, only five months from the start of the Great Recession, 60 economists (not including me) polled by the Wall Street Journal on average forecast at least 2.5 percent annualized growth in real (inflation-adjusted) gross domestic product for each of the four quarters of 2008. The results were quite the opposite: declines of 0.7 percent in the first quarter, 2.7 percent in the third quarter and 6.4 percent in the fourth, with the only increase being 1.5 percent in the second quarter.

Not to Worry!

But not to worry! The recession wasn't officially called until November 28, 2008, almost a year after it had started in December 2007, when the Business Cycle Dating Committee of the National Bureau of Economic Research, a private outfit, announced its decision. This body is the official arbiter of recessions, and everyone accepts its judgment. That includes every presidential administration and every Congress, since no politician wants to be in the business of declaring recessions. In any event, in late November 2008, the consensus could argue that the downturn must be close to completed since the 10 previous post–World War II recessions averaged 10.4 months in length and the longest, the 1973–1975 downturn, spanned 16 months. Subsequently, many, in effect, declared that the Great Recession that they never forecast and never acknowledged up until then was almost over! I found such statements less than reassuring, but surprisingly few of those forecasters joined the mushrooming ranks of the unemployed.

It's also true that the negativity involved in great calls—realism, as I prefer to call it—can be hazardous to employment continuity. I learned that firsthand when I joined Merrill Lynch in 1967 as the firm's first chief economist and established its economic department. In 1969, I forecast a recession to begin late that year and run into 1970. The forecast proved accurate, but it wasn't being bullish on America, in the Merrill Lynch parlance. That put me at odds with Donald T. Regan, who obviously won because he was running the firm. So I took my entire staff and left, ending up at another Wall Street firm, White, Weld, with no idea that Merrill Lynch would buy White, Weld in 1978. So the story on Wall Street, which was absolutely correct, was that Gary Shilling was the only person fired twice by Don Regan. I promptly established my own firm and at least eliminated the risk of being axed by him a third time.

Fundamental Principles

My zeal to detect bubbles and forecast their demise also fits right in with two very fundamental principles that have always guided my forecasting. First, I believe that human nature changes very slowly, if at all, over time. So people will react to similar circumstances in similar ways. This means that history is relevant. Of course, history doesn't repeat itself, but as Mark Twain noted, it does rhyme. This means that forecasting remains an art, not a science. Still, if you can find circumstances in the past that resemble closely those at present, their resolution back then may be a useful guide to future events.

This was clearly true for me in forecasting the 1973–1975 recession. Over a decade earlier, in the early 1960s, while I was pursuing my PhD at Stanford, I spent a summer working at the San Francisco Federal Reserve Bank. The research department was a rather sleepy place at the time, but that gave me lots of time to browse through the library. Most of the books had uniformly dull titles that contained the words Economics or Finance, but an unusual one caught my eye: Hand-to-Mouth Buying and the Inventory Situation, by George A. Gade, published in 1929.

Hand-to-Mouth Buying

The book title came from the reaction to the traumatic events in American goods production and distribution in 1919–1921. After World War I ended in 1918, there were widespread fears that the cancellation of government contracts for military equipment and unemployment among returning soldiers would precipitate a depression. But by early 1919, the opposite unfolded as exports to Europe leaped, credit expanded, and domestic demand surged in reaction to wartime privations. Robust demand soon more than soaked up excess capacity, and prices leaped since wartime price and wage controls had been removed.

Exuberant retail demand worked back to raw material producers, and fears of shortages mushroomed. That encouraged the ordering of many more goods than were needed, both to ensure adequate supplies to meet surging demand and to profit from leaping prices. Inventory levels jumped, but their building created excess demand and artificial shortages that only pushed prices higher an...