![]()

1

An Appraisal of the Complete Denture Situation

Total tooth loss

Perhaps the most fundamental question to ask in the first chapter of a book on complete dentures is: ‘What is the demand for such treatment?’ Fortunately, more and more evidence has become available to provide an increasingly accurate answer and one which enables future trends to be determined with reasonable confidence. Particularly notable are the series of in-depth studies of adult dental health in the UK that have succeeded in painting a detailed picture over a period of more than 30 years. There are also data from Sweden and Finland and parts of Germany that allow some statistical modelling of the current trends (Mojon et al. 2004).

The most detailed picture comes from the UK and the information that follows is based upon decennial surveys, the most recent one undertaken in 1998.

The situation at the end of the twentieth century

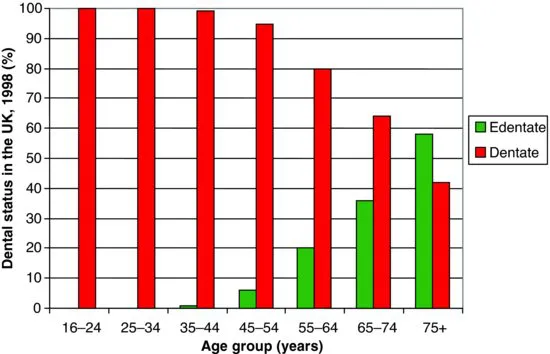

Whilst we await the publication of the survey outlining the state of adult dental health during the first decade of the twenty-first century, let us first look at total tooth loss within adults in the UK in 1998 (Fig. 1.1) (Steele et al. 2000). Overall, 13% of all adults were edentate, and it can be seen that the condition was strongly correlated with age. Total tooth loss was a rarity up to the mid-forties age group, after which there was a steady climb to the age group 75 and over where the majority had lost all their teeth.

Total tooth loss is related not only to age but also to other variables such as social class and marital status. When multivariate analyses were undertaken, any association between tooth loss and gender disappeared. The differences that are apparent in the UK may be illustrated by comparing extremes. To quote from Steele et al. (2000), women from an unskilled manual background living in Scotland were 12 times more likely to have no teeth at all than men from a non-manual background in the south of England. Of those who had lost their remaining teeth in the previous 10 years, 59% stated that they visited the dentist only when troubled whilst 29% said that they had attended their dentist on a regular basis. This pattern of attendance was almost the complete opposite to that of people who still had their own teeth. What is of particular relevance is the change in the rate at which people lost their remaining teeth in the last 10 years of the twentieth century. It has been a much more gradual process than previously. Whereas in 1968 two-thirds of those who were rendered edentulous had 12 or more teeth extracted at the final stage, in 1998 the proportion had gone down to one-quarter. One possible reason for this change is that both patient and dentist wanted to keep some natural teeth for as long as possible. We are fully supportive of this philosophy and enlarge on the topic of transition from the natural to the artificial dentition in Chapter 3.

As people increasingly wish to function with their natural teeth rather than with dentures, one would expect mental barriers to be erected against the latter. This indeed appears to be the case when we consider that, in 1998, over 60% of those people who relied only on natural teeth stated that they would be very upset if they had to function with complete dentures. This attitude seems to have strengthened as we have moved into the twenty-first century. As the number of edentate patients falls, a ‘tipping-point’ appears to have been established, which results in a range of concerns being raised, including the social acceptability of being edentulous. Whilst edentulism was previously thought to be almost inevitable, and thus an ‘acceptable’ option for patients with dental disease, this is no longer the case in many areas of society. As the number of edentulous patients falls, this smaller population becomes more manageable and allows the possibility for this group of people to be offered other treatments. For example, when there is little chance of maintaining a functional natural dentition, first-line treatment options have increasingly moved towards the preservation of some tooth roots and the use of overdentures. When this is not possible, then the use of implant-supported overdentures as the ‘standard of care’ has been proposed (Feine et al. 2002; Thomason et al. 2009).

These changes of emphasis on how one may manage the progression from the dentate state to complete dentures are important, especially as most of the complete denture treatment in the future will inevitably be undertaken on older patients. It is imperative that the dentist is aware of the various treatment opportunities, of the need to explore acceptable alternatives and to move into much longer-term treatment planning whilst the patients still have a functional dentition. This longer-term planning may be best regarded as treatment ‘mapping’ as the absolute plan may need to be more flexible than is commonly the case in many treatment plans.

The past

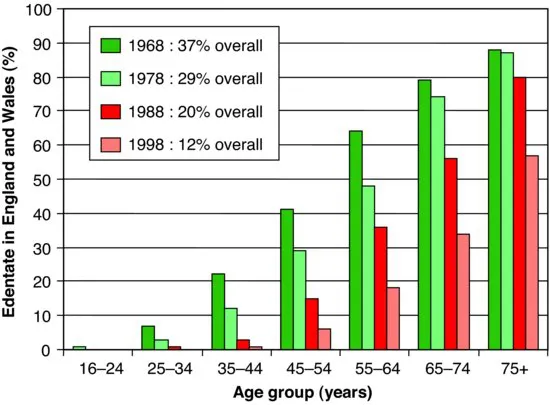

So much for the ‘snap-shot’ of total tooth loss in 1998. A fascinating picture emerges when examining the trends that have developed over the 30-year period during which there have been four studies of adult dental health in England and Wales – 1968, 1978, 1988 and 1998. The relationship of total tooth loss to age is presented in Fig. 1.2. The first point to make is that dental health, as measured by total tooth loss, has improved dramatically. In 1968, 37% of adults in England and Wales had lost all their natural teeth. This figure had gone down to 12% in 1998. This improvement reflects the poor state of oral health before and after World War II when the main thrust of treatment, at the inception of the UK’s National Health Service, had to be an attack on the high levels of neglect, pain and sepsis existing in the community. Once this battle was won, the pattern of extractions and dentures gave way to a desire to restore the teeth and, eventually, to prevent further disease. We are perhaps now seeing the next phase where alternatives and longer-term strategies of management and rehabilitation of what remains can be realistically considered.

The very high percentage of those aged 75 and over who had lost all their teeth at the time of the earlier surveys (Fig. 1.2) is of course a reflection of the high levels of dental disease many years earlier. For example, in 1968, 64% of all those in the age group 55–64 were edentate. That same group of people continued to lose their natural teeth until, 20 years later, 80% of them (now in the 75 and over age group) were edentate.

Referring again to Fig. 1.2, we can see how the huge improvement in oral health of the younger members of the population a few years ago is now influencing the figures as these people enter their middle years. Looking again at the 55–64 age group the percentage that had lost all their teeth has dropped from 64% in 1968 to 18% in 1998. More dramatic still is the reduction in the 45–54 age group – down from 41% to 6% in the same period. As these people grow older, it is reasonable to expect that they will, in 20–30 years time, bring down a lot further the current 57% of those 75 and over who are edentate.

The future

With the mass of information which has been accumulated over the last 30 years, it has become possible to predict future trends with reasonable confidence. If the current trends continue, it is calculated that, by 2018, only 5–6% of the UK adult population will be edentate; let us not forget, though, that 5–6% equates to four million people in the UK. We will need to wait for the results of the 2008–2009 UK Adult Dental Health Survey to see if the UK is still on course for these predicted improvements. On a more salutary note, it has been suggested that the effect of having an ageing population will mitigate against the rate of reduction in the overall prevalence of edentulism in the population. Indeed, in the US it has been predicted that far from decreasing, the need for complete denture treatment will actually increase over the first 2 decades of the twenty-first century (Douglass et al. 2002). The authors argue that the ageing ‘baby boomers’ will more than compensate for the falling prevalence of edentulism. Modelling these changes on European data has suggested that in the UK there will be a reduction in edentulism of the order of 60% over the first 30 years of the century, but it will then remain stable. The mean prediction for Finland follows a similar picture to the UK but the spread of the data is very wide and so is inconclusive (Mojon et al. 2004).

Total tooth loss in other countries

An investigation into the oral health of adults in the Republic of Ireland was undertaken in 1989–1990 (O’Mullane & Whelton 1992). The level of total tooth loss was very similar to that in England, Wales and Northern Ireland in 1988. There had been a considerable decline in the level of edentulousness compared with 10 years earlier.

The relationship of total tooth loss to age is a worldwide phenomenon, as shown in Table 1.1, where the percentage of edentulous individuals for two age groups in a number of countries is shown. The amount of total tooth loss recorded in or around 1990 varies considerably between countries (WHO 1992). Whilst most EU countries do not have national survey data, in France a recent survey in the region Rhone-Alpes reported that in 1995, 16% of the 65–74 age-band was edentulous compared with 36% for the UK and 34% for the region of Pomerania in Germany (Mojon et al. 2004).

Table 1.1 The percentage of people aged 35–44 years and 65 years and over with no natural teeth (data from WHO (1991)).

| Albania | 3.7 | 69.3 |

| Czechoslovakia | 0.7 | 38.3 |

| Denmark | 8.0 | 60.0 |

| Finland | 9.0 | 46.0 |

| Ex-GDR | 0.5 | 58.0 |

| Germany, Federal Republic | 0.4 | 27.0 |

| Hungary | 0.3 | 30.0 |

| Ireland | 4.0 | 49.0 |

| Italy | 0.3 | 18.0 |

| The Netherlands | 9.4 | 65.4 |

| Norway | 1.0 | 31.0 |

| Romania | 15.0 | 55.8 |

| San Marino | 1.3 | 40.7 |

| Sweden | 1.0 | 20.0 |

| Turkey | 2.7 | 75.0 |

| United Kingdom | 4.0 | 67.0 |

| (Former) Yugoslavia | 0.6 | 33.0 |

The prospects for the future may be summarised as follows:

- It is unlikely that the edentulous state will disappear, but there probably will be a fall in those requiring complete dentures so that there will be around 60% of the current number required.

- More people will retain a functional natural dentition into old age, but this dentition will not last a lifetime in all cases.

- As the public’s expectations for oral health continue to rise, a larger proportion of those who lose their teeth will be very upset about the prospect of having to wear complete dentures and this will influence their response to treatment. Therefore, it will be critical to consider alternative treatment strategies for these patients.

- Most complete denture treatment will be centred on older people and is, therefore, likely to become more complex and demanding. The opportunities to consider retaining teeth as overdenture abutments or to provide osseointegrated implants as overdenture abutments for this group of patients are likely to increase and decisions will have to be made at an appropriate time in the planning cycle.

- Dentists will continue to need complete denture skills, which will have to be of a high order (Steele et al. 2000). Nevertheless, there will be less opportunity for the majority of dentists to practice these skills on a regular basis and some parts of this treatment provision are likely to move into the realm of the specialist.

In the remainder of this book, we endeavour to deal with all these points.

The limitations of complete dentures

The limitations of complete dentures are highlighted when one compares the difference between functioning natural teeth, intimately connected to and embedded in living tissues, with the removable prosthesis which replaces them, constructed of an artificial material simply resting on vital living (and often delicate) tissues. Between these two extremes is the complete overdenture. Whilst having many of the characteristics of t...