![]()

Part 1

First Principles

![]()

1.1

First Principles

Most traditional building materials are relatively weak in tension, when compared to their compressive strength. If a building is distorted, by whatever force, some parts of it will be stretched. Cracking is likely to occur at right angles to the force that caused the stretching. By imagining arrows at right angles to a crack, it is possible to determine the direction of movement. The direction of the movement is usually directly related to its cause. There are, however, always some cracks that cannot be diagnosed quickly by a simple visual inspection.

The over riding first principle that one must understand when diagnosing cracking is that the materials we are dealing with, bricks and concrete, are weak in tension.

STEP ONE

Brickwork and most materials crack when pulled apart in tension. Tension is caused by elongation (Figure 1.1.1).

Imagine a square or rectangle of material – A, B, C, D.

Think of this as the front elevation of a building or a panel of part of a building.

Within normal tolerances buildings are built square and plumb.

In a square or rectangle the diagonals are the same length. Please measure them. A–C is the same length as B–D (Figure 1.1.2).

Please write the measurements down.

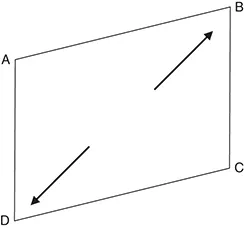

If the left hand side settles, the diagonal A–C is shortened. It is put into compression (Figure 1.1.3).

The diagonal B–D is lengthened. It is put into tension.

Please measure B–D and write the measurements down. You will see that it is longer than it was. It is this stretching that is important as it creates tension.

The tension force pulls the panel apart, in tension. If it was brickwork it would pull it thus.

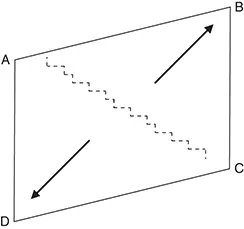

The crack would be perpendicular to the elongation. THE CRACK IS AT A RIGHT ANGLE TO THE TENSION.

This is always the first point to look at when observing cracks. The movement is at right angles to the crack. The building has either moved up to the right hand side or down to the left hand side. There are very few reasons for upward movement and this possibility can quickly be assessed and usually dismissed. Buildings are heavy and gravity pulls them down. It is the downward arrow that is usually significant.

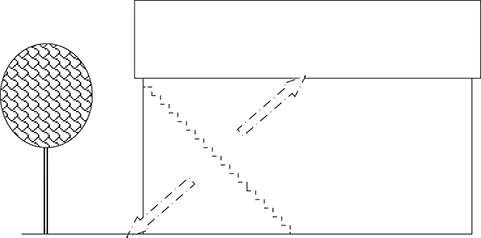

Example 1

If one imagines arrows at right angles to the crack, as shown dashed in the diagram in Figure 1.1.4, then one can see that the movement is either down to the left hand corner or up to the right hand side. The arrows point to where the movement is and this is usually pointing at the defect. In this case one would look down to the left and there is the tree. Alternatively, the movement could be up to the right hand side. This is very unlikely and in this case there is nothing that could possibly cause movement up to the right. The solution is therefore reasonably obvious. In the absence of other evidence the movement is likely to be caused by the tree.

There are some instances where upward movement can occur in buildings; the most common being clay heave or corrosion of steel fixings and wall ties. Although upward movement is far less likely than downward movement the possibility of upward movement should be assessed before dismissing the possibility.

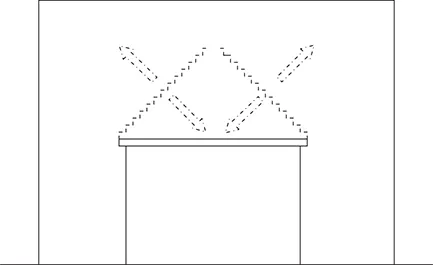

Example 2

It is quite common to see diagonal cracking above an opening in a brick wall, similar to that shown in the diagram in Figure 1.1.5. The cracking forms a triangle running diagonally through the brick courses at around 45° from the support points at either side.

Once again, imagine arrows at right angles to the cracks as shown in the diagram. In this case two of the imaginary arrows at right angles to the cracks intersect on the lintel – good evidence. In fact if two arrows intersect at the same point it is almost certainly the position of the defect. The two arrows pointing up contradict each other, one up to the left and one up to the right. The solution is again obvious. The movement is deflection of the lintel (beam) supporting the masonry above the opening.

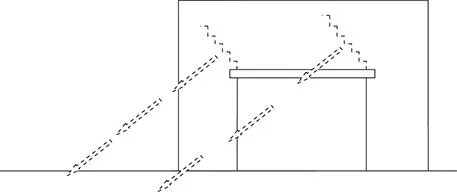

Example 3

Look at a very similar situation in Figure 1.1.6.

Imagine arrows at right angles to the cracks. There is no reason for upwards movement here so the arrows pointing up to the right are dismissed. The other arrows show movement down to the left.

The arrows running from the right hand side first intersect on the lintel. Could it be lintel deflection? If it was lintel deflection the arrows from the left hand crack would also point to the lintel, as they did in the previous example. These arrows go down to the left hand side. If it is not the lintel, continue the arrows from the right hand side down, and they point to the next area, being the left hand pier to the side of the opening. There are two cracks, and both sets of arrows point down to the left hand side. The cause of the movement is there, in the left hand pier. Having established where the movement is, we now have to work out why.

In this case study there is not enough information to work out why. The settlement in the left hand pier could simply be caused by load concentration. It could be poor foundations or poor soil bearing capacity. In real life, there might be a tree or a defective drain nearby.

We would have to collect that information sequentially on site, in order to work out which would be the most probable. If there was no tree or no drain, and the movement was significant in magnitude, we may have to arrange for some trial pits to be dug, in order to determine the nature of the foundations and the subsoil. Only then might it be possible to make the final diagnosis. There will inevitably be cracks that cannot be definitively diagnosed on the basis of one visual inspection.

![]()

1.2

Crack Patterns and Cracks

By following the simple principles of tension and compression, most cracks can be diagnosed quickly. There are however, a number of things that can distort crack patterns. By understanding the factors that distort the shape and direction of a crack, a more reliable diagnosis can be made.

By the simple application of the First Principles in STEP 1 most cracks can be diagnosed within a few minutes. Probably around nine out of ten cracks can be diagnosed almost immediately. By sketching a diagram similar to those in the examples, denoting the building, pattern of the cracks and arrows of tension at right angles to the crack; the position of the movement will usually be obvious.

There are however, several factors that can distort the way cracks appear. To improve the success rate of diagnosis these factors need to be understood.

![]()

1.3

Rotational Movement

When buildings subside they are unlikely to descend evenly. As one part goes down in relation to another part, there is a ‘hinge’ effect. The hinge effect causes rotation to occur. This increases the horizontal displacement of the crack with height. Cracks created by subsidence or settlement are likely to taper, being narrow at the base and wider at the top.

When a building is affected by subsidence, it rarely drops straight down. In order for a building to drop straight down, the subsidence would have to be evenly distributed around the entire area of the building. That is not usually the case. A defect in one area is the usual cause of subsidence, which then spreads from the epicentre of the defect.

For example, Figure 1.3.1 shows a typical subsidence crack, caused b...