![]()

1

The Hedge Fund Industry

The global credit crisis originated from a growing bubble in the US real estate market which eventually burst in 2008. This led to an overwhelming default of mortgages linked to subprime debt to which financial institutions reacted by tightening credit facilities, selling off bad debts at huge losses and pursuing fast foreclosures on delinquent mortgages. A liquidity crisis followed in the credit markets and banks became increasingly reluctant to lend to one another, causing risk premiums on debt to soar and credit to become ever scarcer and more costly. The global financial markets went into meltdown as a continuing spiral of worsening liquidity ensued. When the credit markets froze, hedge fund managers were unable to get their hands on enough capital to meet investor redemption requirements. Not until early 2009 did the industry start to experience a marked resurgence in activity, realising strong capital inflows and growing investor confidence.

This chapter introduces the concept of hedge funds and how they are structured and managed, as well as discussing the current state of the global hedge fund industry in light of the recent financial crisis. Several key investment techniques that are used in managing hedge fund strategies are also discussed. The chapter aims to build a basic working knowledge of hedge funds and, along with Chapters 2 and 3, to develop the fundamentals necessary in order to approach and understand the more quantitative and theoretical aspects of their modelling and analysis developed in later chapters.

1.1 WHAT ARE HEDGE FUNDS?

Whilst working for Fortune magazine in 1949, Alfred Winslow Jones began researching an article on various fashions in stock market forecasting and soon realised that it was possible to neutralise market risk1 by buying undervalued securities and short selling (see Section 1.4.1) overvalued ones. Such an investment scheme was the first to employ a hedge to eliminate the potential for losses by cancelling out adverse market moves, and the technique of leverage2 to greatly improve profits. Jones generated an exceptional amount of wealth through his hedge fund during the 1950s and 1960s and continually outperformed traditional money managers. Jones refused to register the hedge fund with the Securities Act 1933, the Investment Advisers Act 1940, or the Investment Company Act 1940, his main argument being that the fund was a private entity and none of the laws associated with the three Acts applied to this type of investment. It was essential that such funds were treated separately from other regulated markets since the use of specialised investment techniques, such as short selling and leverage, were not permitted under these Acts, nor was the ability to charge performance fees to investors.

So that the funds maintained their private status, Jones would never publicly advertise or market the funds but only sought investors through word of mouth, keeping everything as secretive as possible. It was not until 1966, through the publication of a news article about Jones's exceptional profit-making ability, that Wall Street and high net worth3 individuals finally caught on, and within a couple of years there were over 200 active hedge funds in the market. However, many of these hedge funds began straying from the original market neutral strategy used by Jones and employed other apparently more volatile strategies. The losses investors associated with highly volatile investments discouraged them from investing in hedge funds. Moreover, the onset of the turbulent financial markets experienced in the 1970s practically wiped out the hedge fund industry altogether. Despite improving market conditions in the 1980s, only a handful of hedge funds remained active over this period. Indeed, the lack of hedge funds around in the market during this time changed the regulators’ views on enforcing stricter regulation on the industry. Not until the 1990s did the hedge fund industry begin to rise to prominence again and attract renewed investor confidence.

Nowadays, hedge funds are still considered private investment schemes (or vehicles) with a collective pool of capital only open to a small range of institutional investors and wealthy individuals and having minimal regulation. They can be as diverse as the manager in control of the capital wants to be in terms of the investment strategies and the range of financial instruments which they employ, including stocks, bonds, currencies, futures, options and physical commodities. It is difficult to define what constitutes a hedge fund, to the extent that it is now often thought in professional circles that a hedge fund is simply one that incorporates any absolute return4 strategy that invests in the financial markets and applies non-traditional investment techniques. Many consider hedge funds to be within the class of alternative investments, along with private equity and real estate finance, that seek a range of investment strategies employing a variety of sophisticated investment techniques beyond the longer established traditional ones, such as mutual funds.5

The majority of hedge funds are structured as limited partnerships, with the manager acting in the capacity of general partner and investors as limited partners. The general partners are responsible for the operation of the fund, relevant debts and any other financial obligations. Limited partners have nothing to do with the day-to-day running of the business and are only liable with respect to the amount of their investment. There is generally a minimum investment required by accredited investors6 of the order of $250,000 to $500,000, although many of the more established funds can require minimums of up to $10 million. Managers will also usually have their own personal wealth invested in the fund, a circumstance intended to further increase their incentive to consistently generate above average returns for both the clients and themselves. In addition to the minimum investment required, hedge funds will also charge fees, the structure of which is related to both the management and performance of the fund. Such fees are not only used for administrative and ongoing operating costs but also to reward employees and managers for providing above average positive returns to investors. A typical fee basis is the so-called 2 and 20 structure which consists of a 2% annual fee (levied monthly or quarterly) based on the amount of assets under management (AuM) and a 20% performance-based fee, i.e. an incentive-oriented fee. The performance-based fee, also known as carried interest, is a percentage of the annual profits and only awarded to the manager when they have provided requisite returns to their clients. Some hedge funds also apply so-called high water marks to a particular amount of capital invested such that the manager can only receive performance fees, on that amount of money, when the value of the capital is more than the previous largest value. If the investment falls in value, the manager must bring the amount back to the previous largest amount before they can receive performance fees again. A hurdle rate can also be included in the fee structure, representing the minimum return on an investment a manager must achieve before performance fees are taken. The hurdle rate is usually tied to a market benchmark, such as LIBOR7 or the one-year T-bill rate plus a spread.

1.2 THE STRUCTURE OF A HEDGE FUND

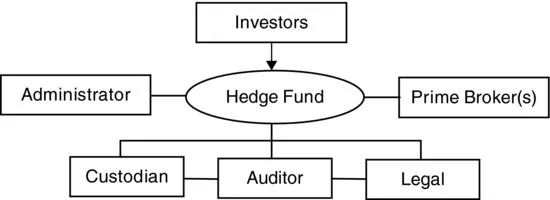

In order for managers to be effective in the running of their business a number of internal and external parties covering a variety of operational roles are employed in the structure of a hedge fund, as shown in Figure 1.1. As the industry matures and investors are requiring greater transparency and confidence in the hedge funds in which they invest, the focus on the effectiveness of these parties is growing, as are their relevant expertise and professionalism. Hedge funds are also realising that their infrastructure must keep pace with the rapidly changing industry. Whereas in the past some funds paid little attention to their support and administrative activities, they are now aware that the effective operation of their fund ensures the fund does not encounter unnecessary and unexpected risks.

1.2.1 Fund Administrators

Hedge fund administrators deal with many of the operational aspects of the successful running of a fund, such as compliance with legal and regulatory rulings, financial reporting, liaising with clients, provision of performance reports, risk controls and accounting procedures. Some of the larger established hedge funds use specialist in-house administrators, whilst smaller funds may avoid this additional expense by outsourcing their administrative duties. Due to the increased requirement for tighter regulation and improved transparency in the industry, many investors will only invest with managers who can prove that they have a strong relationship with a reputable third-party administrator and that the proper processes and procedures are in place. The top five global administrators in 2010 were CITCO, HSBC, Citigroup, GlobeOp and Custom House.

Hedge funds with offshore operations often use external adminis-trators in offshore locations to provide expert tax, legal and regu-latory advice for those jurisdictions. Indeed, it is a requirement in some offshore locations (e.g. the Cayman Islands) that hedge fund accounts must be regularly audited. In these cases, administrators with knowledge of the appropriate requirements in those jurisdictions would fulfil this requirement.

1.2.2 Prime Brokers

The prime broker is an external party who provides extensive services and resources to a hedge fund, including brokerage services, securities lending, debt financing, clearing and settlement, and risk management. Some prime brokers will even offer incubator services, office space and seed investment for start-up hedge funds. The fees earned by prime brokers can be quite consi...