eBook - ePub

Homes and Homecomings

Gendered Histories of Domesticity and Return

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Homes and Homecomings

Gendered Histories of Domesticity and Return

About this book

In Homes and Homecomings an international group of scholars provide inspiring new historical perspectives on the politics of homes and homecomings. Using innovative methodological and theoretical approaches, the book examines case studies from Africa, Asia, the Americas and Europe.

- Provides inspiring new historical perspectives on the politics of homes and homecomings

- Takes an historical approach to a subject area that is surprisingly little historicised

- Features original research from a group of international scholars

- The book has an international approach that focuses on Africa, Asia, the Americas and East and West Europe

- Contains original illustrations of homes in a variety of historical contexts

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Homes and Homecomings by K. H. Adler, Carrie Hamilton, K. H. Adler,Carrie Hamilton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Historiography. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Communist Comfort: Socialist Modernism and the Making of Cosy Homes in the Khrushchev Era

The theme of this chapter – ‘communist comfort’ and the propagation, in Soviet mass housing of the 1950s-60s, of a socialist modernist aesthetics of domesticity – is rich with oxymoron.1

First, modernism was assigned, in the Cold War’s binary model of the world, exclusively to the capitalist ‘camp’. ‘Socialist’ and ‘modernist’ were positioned as incompatible. Although the conjunction of political and artistic radicalism in Soviet Russia of the 1920s is well known, the renascence there in mid-century of socialist modernism was unthinkable in Cold War terms and has only recently begun to be taken seriously.2

The second contradiction is that between modernity – along with its cultural manifestation, modernism – and domesticity. Modernity and dwelling have been assumed to be at odds. Pathologised by Walter Benjamin and others as a nineteenth-century petit-bourgeois addiction, domesticity and the need for comfort were to be shrugged off in favour of the freedom to roam. Homelessness, and not ‘homeyness’, was the valorised figure of modernity.3 In revolutionary Russia of the 1920s, the modernist avant-garde designed portable, fold-away furniture more suited to the military camp; to supplant the soft, permanent bed of home was part of their effort to make the material culture of everyday life a launch pad to the radiant future.4 Adopting unchallenged the established cultural identification between women and the bourgeois home, modernism’s (and socialism’s) antipathy for domesticity was also gendered, indeed misogynistic. Its wandering, exploring hero was imagined as male, while the despised aesthetics of dwelling from which he walked away – entailing ornament, concealment, confinement and the use of soft, yielding materials – particularly textiles – was construed not only as bourgeois but as feminine.5 That the condition of modernity was to be restless, transient, constantly on the move became, however, a source of regret and nostalgic yearning for some after the destruction and dislocations of the Second World War. The philosopher Martin Heidegger, writing in 1954, lamented that in modern industrial society people had lost the capacity to dwell. It was particularly hard, he found, to be at home and at peace in modern housing, which is produced as a commodity or allocated by state bureaucracies, because we no longer reside in what we or our kin have built through generations but instead pass through the constructions of others.6

Third, the terms ‘communist comfort’ or ‘socialist domesticity’ are also, at first sight, as self-contradictory as ‘fried snowballs’. ‘Cosy’ is unlikely to be the word that leaps to mind in association with Soviet state socialism, and least of all with the standard, prefabricated housing blocks that were erected at speed and in huge numbers in the late 1950s, which form the material context for this study. Indeed, home-life has hardly been the dominant angle from which to study the Soviet Union.7 Socialism as a movement was traditionally associated with asceticism, sobriety and action; with production rather than consumption and rest; and with the collective, public sphere rather than the domestic and personal. Meanwhile, nineteenth-century socialist and feminist critiques, including those of Marx and Engels, identified the segregated bourgeois home as the origin of division of labour and alienation and a primary site of class and gender oppression. The bourgeois institutions of home and family, based on private property bonds, were supposed to be cleared away by the Bolshevik Revolution of 1917. John Maynard Keynes, speaking of left-leaning students in the 1930s, noted that, ‘Cambridge undergraduates were never disillusioned when they took their inevitable trip to “Bolshiedom” and found it “dreadfully uncomfortable”. That is what they are looking for’.8

If disdain for bourgeois domesticity was a stance sympathisers expected of the Soviet Union, neglect of human comfort was also one of the charges its detractors levelled against it. In the Cold War, Western accounts of the Soviet Union tended to focus on political repression and military hardware paraded in the public square. When Soviet Russian everyday life was addressed at all, it was in negative terms of lack and shortage, embodied in queues for basic necessities. Stereotypes of drab, austere comfortlessness reinforced the West’s indictment and ‘othering’ of state socialism as the polar opposite of the Western, capitalist model of ever-increasing comfort, convenience and individual, home-based consumption.9 The Soviet home, if it came within the sights of Western attention at all, stood – by contrast with Western prosperity – for the privation of Soviet people, their lack of privacy, convenience, choice, consumer goods and comforts. Alternatively, it figured as a flaw in the Soviet system’s ‘totalitarian’ grasp, its Achilles heel, a site of resistance to public values, of demobilisation in face of the mobilisation regime’s campaigns, and even a potential counter-revolutionary threat to the interventionist state’s modernising project of building communism. Thus one Western observer surmised in 1955: ‘if Russians got decent homes, TV sets and excellent food wouldn’t they, being human, begin to develop a petit-bourgeois philosophy? Wouldn’t they want to stay home before the fire instead of attending the political rally at the local palace of culture?’10 Others asked, ‘Can the Soviet system afford to allow a larger-scale retreat from the world of work and of collectivity to the world of cosy domesticity on the part of its women?… A type of socialism might appear that proved to be so pleasant that the distant vision of communism over the far horizon might cease to beckon’.11

You could have either communism or comfort, according to this model, not ‘comfortable communism’ or ‘communist comfort’. Home and utopia – no-place – were incompatible. If comfortable homes were deemed by Cold War observers to exist at all in the Soviet Union then it was as spaces where the official utopia of the party-state was contradicted, as sites of potential resistance and as the germ of state socialism’s potential undoing.

Associated with women’s traditional roles as preservers of continuity with the past, with conventional female qualities and handed-down practices and know-how, the home’s status as the recalcitrant last frontier of state modernisation was gendered. Thus Francine du Plessix Gray, a Russian émigrée resident in the United States, represents the Soviet Russian home as an antidote to official Soviet values:

Moscow’s other havens, of course, were and remain the homes of friends: Those padded, intimate interiors whose snug warmth is all the more comforting after the raw bleakness of the nation’s public spaces; those tiny flats, steeped in the odor of dust and refried kasha in which every gram of precious space is filled, every scrap of matter – icons, crucifixes, ancient wooden dolls, unmatched teacups preserved since before the Revolution – is stored and gathered against the loss of memory.12

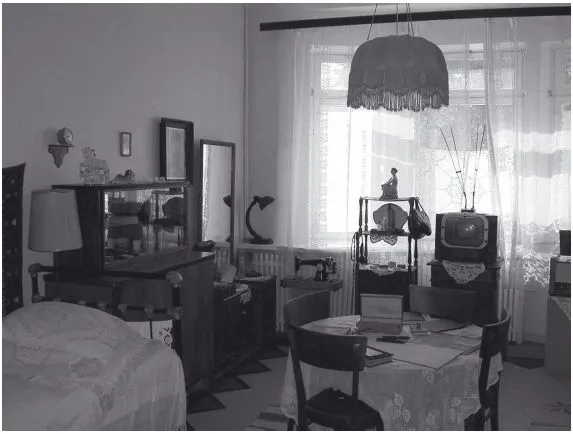

There, in Gray’s view, authentic Russian qualities were preserved in spite of over sixty years of Soviet rule. Paramount among these is an apparently timeless and indomitable ‘national tradition of uyutnost’ [sic]: that dearest of Russian words, approximated by our “coziness” and better by the German Gemütlichkeit, denotes the Slavic talent for creating a tender environment even in dire poverty and with the most modest means’. Uiutnost’ is ‘associated with intimate scale, with small dark spaces, with women’s domestic generosity, and with a nurturing love’.13 It represents, in Gray’s elegiac account, continuity between generations of women. The womb-like embrace of the Russian home is defined by explicit antithesis to an inhospitable, inhuman public sphere and to the chiliasm and collectivism of official ideology and culture. The opposition between the home and the Soviet state’s official modernising project, which entailed rupture with the past, is represented in a series of negative/positive dyads that map onto the dichotomy public/private: bleak/snug; raw/cooked (or even recooked!); loss/gathering and storing; amnesia/memory. The striving, future-oriented public project of Soviet modernity, based on Enlightenment values of rationality, science and progress, is opposed by home as a warm, hospitable, unchanging and essentially feminine domain of authentic human relations materialised in ‘scraps of matter’ and unmatched teacups. The home appears as a hermetic cell, apparently untouched by historical contingency and the ruptures of the twentieth century. Padded by the accumulation of memories and memorabilia, dust and clutter, it is insulated from ideological intrusion, scientific and industrial progress, in short, from modernity and its specific Soviet mode (Figure 1).

One can almost hear Benjamin scream in his sleep. For the private realm Gray celebrates here is the stuff of any Marxist modernist’s worst nightmares (dreams a Freudian might analyse in terms of fear of being absorbed back into the womb).14 In such a space, even Faust might succumb to the temptation to abide and give up the quest for enlightenment. For many Soviet commentators, too, in the late 1950s and early 1960s, the period on which we focus here, the resilience of what they considered a regressive aesthetics of hyper-domesticity and bad taste among the Soviet people aroused fear of loss of political consciousness. But was the contradiction between domesticity and socialist modernity irreconcilable? Or could home be accommodated in the modernist, socialist utopia? If so, what should it look like? In what follows we will examine ways in which specialist agents in the Khrushchev era (1953–64) sought to overcome the contradiction between domesticity and socialist modernity and to delineate a modern socialist aesthetics of the domestic interior. As Gray indicated, the key Russian term in the image of homeliness is uiut, a word that encompasses both comfort and cosiness or snugness.15 Intelligentsia experts redefined uiut in modernist terms. Did popular practice follow their prescription? Or did the material practices of uiut remain closer to a retrospective ideal of ‘homeyness’, as defined by anthropologist Grant McCracken, as the expression of a search for continuity, stability, and a sense of rootedness?16 In the concluding section we will turn briefly to whether the aesthetics of modern housing and modernist advice were embraced, resisted, subverted or accommodated by primarily female homemakers in their homes.

Figure 1: Reconstruction of a Stalin-era domestic interior (Sillamae Ethnographic Museum, photo: Dmitrii Sidorov).

An obsession with domesticity

In Boris Pasternak’s 1957 novel, Doctor Zhivago, Lara (whose name references the Lares), watching a young girl construct a home for her doll in spite of the dislocations of the Revolution, comments on her instinct for domesticity and order: ‘nothing can destroy the longing for home and for order’.17 Unlike Pasternak’s heroine, we should not take for granted, as some ahistorical, biological given, that the longing for home and order, for comfort and cosiness, are mandatory for dwelling, that these are essentially feminine instincts, or that domestic spaces need necessarily be projections of the occupant’s self. Along with other apparently natural categories, such as childhood, the identification of home with comfort has to be historicised as the cultural product of particular historical and material circumstances. The emergence of the concept of comfort, like that of the ‘private’ to which it is closely aligned, was associated with industrialisation, the rise of the bourgeoisie, and the segregation of the home as a private sphere and women’s domain, to which the exhausted male could return from the world of work and public life.18 In the Soviet Union, the conditions for this historical phenomenon were supposed to be swept away: bourgeois capitalism, women’s confinement in the segregated home, and the idea of home as a fortress of private property values.

Yet Soviet culture of the Khrushchev era, it is no exaggeration to say, became obsessed with homemaking and domesticity. This was a matter both of authoritative, specialist practice and intelligentsia discourse on one hand, and of popular culture and experience on the other. Soviet public discourse, whether intentionally or as an unintended effect, naturalised cosiness and comfort as essential attributes of home life, and as a legitimate concern of the modern Soviet person, especially women. The domestic interior was presented not only as a place to carry out everyday reproductive functions, but also as a site for self-projection and aesthetic production, where the khoziaika (housekeeper or, more literally, mistress of the house) displayed her taste and creativity. It involved making things for the home and exercising judgement in selecting, purchasing, adapting and arranging the products of mass serial production. What were the historical conditions for the preoccupation with home decorating?

The material premises for the production of domesticity began, at last, to be provided on a mass scale in the Khrushchev era. The shift of priorities towards addressing problems of mass living standards, housing and consumption had already begun before Stalin’s death, at the Nineteenth Party Congress in October 1952, but the pace intensified from 1957 as the provision of housing and consumer goods became a pitch on which the post-Stalin regime staked its legitimacy at home and abroad. A party decree of 31 July 1957 launched a mass industrialised housing construction campaign: ‘Beginning in 1958, in apartment houses under construction both in towns and in rural places, economical, well-appointed apartments are planned for occupancy by a single family’.19 The results would transform the lives of millions over the next decade. Some 84.4 million people – over one third of the entire population of the USSR – moved into new accommodation between 1956 and 1965, while others improved their living conditions by moving into modernised or less cramped housing.20 The construction of new regions of low-rise, standard, prefabricated apartment blocks fundamentally altered the urban – and even rural – environment, extending the margins of cities and accelerating the already rapid process of urbanisation. Above all, the new flats were designed for occupancy by single families, in place of the prevailing norm of collective living in either barracks or communal apartments (Figure 2).

A range of bureaucracies and specialist agents of the party-state were necessarily involved in shaping the interior, given the mass scale and industrial methods of construction and the accompanying shift towards serial production of consumer goods to furnish them. At the same time, the increased provision of single-family apartments could, it was feared, foster regressive, particularist mentalities and loss of political consciousness. It was necessary therefore to work actively to forestall this. Thus architects and designers, trade specialists, and health, hygiene and taste experts were concerned not only with shaping the material structure of apartments, but with defining how people should furnish and dwell in them.

Figure 2: 1960s standard apartment block, St Petersburg (photo: Ekaterina Gerasimova, 2004 for project Everyday Aesthetics in the Modern Soviet Flat).

But, the obsession with homemaking and the terms of domesticity was also shared by the millions of ordinary citizens who moved into new or modernised living quarters, or who could realistically expect to do so in the near future. Moving in, they had to furnis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- series

- title

- copyright

- NOTES ON CONTRIBUTORS

- Gendering Histories of Homes and Homecomings

- 1: Communist Comfort: Socialist Modernism and the Making of Cosy Homes in the Khrushchev Era

- 2: Corporate Domesticity and Idealised Masculinity: Royal Naval Officers and their Shipboard Homes, 1918–39

- 3: Men Making Home: Masculinity and Domesticity in Eighteenth-Century Britain

- 4: ‘Who Should Be the Author of a Dwelling?’ Architects versus Housewives in 1950s France

- 5: Ideal Homes and the Gender Politics of Consumerism in Postcolonial Ghana, 1960–70

- 6: ‘The Dining Room Should Be the Man’s Paradise, as the Drawing Room Is the Woman’s’: Gender and Middle-Class Domestic Space in England, 1850–1910

- 7: ‘There Is Graite Odds between A Mans being At Home And A Broad’: Deborah Read Franklin and the Eighteenth-Century Home

- 8 Sexual Politics and Socialist Housing: Building Homes in Revolutionary Cuba

- 9: ‘The White Wife Problem’: Sex, Race and the Contested Politics of Repatriation to Interwar British West Africa

- 10: From Husbands and Housewives to Suckers and Whores: Marital-Political Anxieties in the Anxieties in the ‘House of Egypt’, 1919–48

- 11: Double Displacement: Western Women’s Return Home from Japanese Internment in the Second World War

- index