- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

NMR in Organometallic Chemistry

About this book

The first and ultimate guide for anyone working in transition organometallic chemistry and related fields, providing the background and

practical guidance on how to efficiently work with routine research problems in NMR.

The book adopts a problem-solving approach with many examples taken from recent literature to show readers how to interpret the data.

Perfect for PhD students, postdocs and other newcomers in organometallic and inorganic chemistry, as well as for organic chemists

involved in transition metal catalysis.

practical guidance on how to efficiently work with routine research problems in NMR.

The book adopts a problem-solving approach with many examples taken from recent literature to show readers how to interpret the data.

Perfect for PhD students, postdocs and other newcomers in organometallic and inorganic chemistry, as well as for organic chemists

involved in transition metal catalysis.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access NMR in Organometallic Chemistry by Paul S. Pregosin in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Physical Sciences & Organic Chemistry. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

Just as in organic chemistry or biochemistry, it is now routine to measure 1H, 13C, and, often, 31P NMR spectra of diamagnetic organometallic and coordination compounds. Many NMR spectra are measured simply to see if a reaction has taken place as this approach can take sometimes take <5min. Having determined that something has happened, the most common reasons for continuing to measure are usually associated with

1) Confirmation that a reaction has taken place and, by simply counting the signals, deciding how to proceed

2) The recognition of new and/or novel structural features via marked changes in chemical shifts and/or J-values, and

3) The need for a unique probe with sufficient “structural resolution” to follow the kinetics or the development of a reaction.

When a P atom is present, proton-decoupled 31P NMR often represents one of the simplest analytical tools available as the spectra can be obtained quickly and do not normally contain many lines.

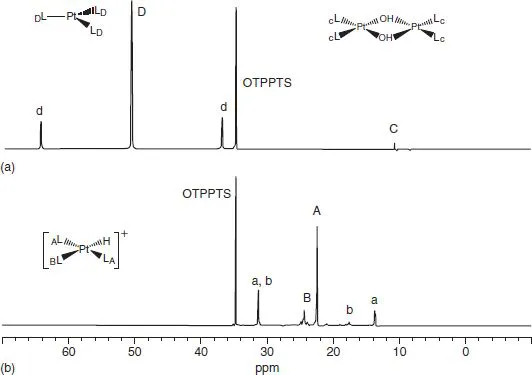

Figure 1.1 shows the 31P NMR spectra for aqueous solutions of the Pt(0) and Pt(II) complexes Pt(TPPTS)3, D, and Pt(H)(TPPTS)3+, A, respectively, as a function of pH (TPPTS is the water-soluble triphenyl phosphine derivative P(m-NaSO3C6H4)3). At pH 13, the Pt(0) complex is stable, while at pH 4, the hydride cation is preferred. The lowercase letters indicate the 195Pt satellites. One isotope of platinum, 195Pt, has I = 1/2 and 33.7 natural abundance, and the separation of these satellite lines represents 1J(95Pt, 31P), another useful tool. Using 31P rather than 1H or 13C provides a quick and easy overview of the changes in the chemistry and corresponds to point 1.1)

Figure 1.1 31P NMR spectra recorded on the same solution after 10 cycles between pH 4 and 13: (a) recorded at pH 13, showing the Pt(0) complex, D, Pt(TPPTS)3, and (b) recorded at pH 4, showing Pt(H)(TPPTS)3 cation, A. Traces of the hydroxide-bridged dinuclear complex, C, as well as the phosphine oxide, OTPPTS, are marked [1].

Apart from recognizing the number of different chemical environments, many times the important clue(s) with respect to the nature/and or source of the reaction products stem from specific chemical shifts.

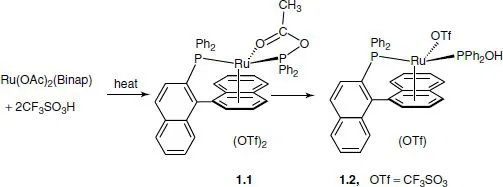

Reaction of Ru(OAc)2(Binap) with 2 equivalents of the strong acid CF3SO3H affords the product 1.2 in high yield. Superficially, complex 1.2 appears to arise as a result of the addition of H2O across a Binap P-C bond. But what is the water source? The 13C spectrum of the reaction solution, see Figure 1.2, reveals that acetic anhydride is produced (and thus water) from the two molecules of HOAc produced from the protonation. Further, the spectrum shows a C=O signal for the novel intermediate 1.1.

This reaction represents an example of point 2, in that the product reveals an unexpected feature.

Figures 1.3 and 1.4 demonstrate point 3. The 1H NMR spectrum of the deuterated rhodium pyrazolylborate isonitrile complex, RhD(CH3)(Tp′)(CNCH2But), in the methyl region, slowly changes to reveal the isomer in which the deuterium atom in now incorporated in the methyl group to afford RhH(CH2D)(Tp′)(CNCH2But). In this chemistry, the deuterium isotope effect on the 1H methyl chemical shift is sufficient to allow the resolution of the two slightly different methyl groups and thus allow the 1H(2H) exchange to be followed.

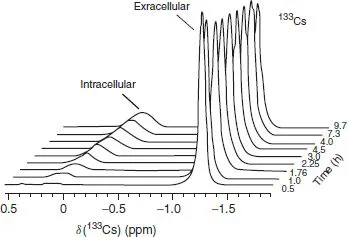

Figure 1.4 shows the intracellular and extracellular exchange of cesium, via 33Cs NMR (I = 7/2, 100% abundant), as a function of time. Although this subject does not involve transition metal chemistry, it does demonstrate how NMR can shed light on a potentially complicated biological subject. Both Figures 1.3 and 1.4 represent examples of the use of NMR to follow a slowly developing chemical transformation (point 3).

To be fair, a unique structural assignment cannot usually be made by counting the number of 1H, 13C, or 31P signals and/or measuring their chemical shifts. X-ray crystallography remains the acknowledged ultimate structure proof. However, for monitoring reactions, identifying mixtures of products and detailed mechanistic studies involving varying structures, NMR has proven to be a flexible and unique methodology. Apart from 1H, 13C, 15N, 19F, or 31P, already mentioned, there are many other possibilities, including 2H, 29Si, one of the Sn isotopes, and 195Pt, to mention only a few.

Figure 1.2 Section of the 13C spectrum of the reaction solution after 30min at 353 K with peaks for the acetate moiety of 1.1, acetic acid, and acetic anhydride. The expanded section shows the P C coupling, 2J = 2 Hz (75MHz in 1,2-dichloroethane solution) [2].

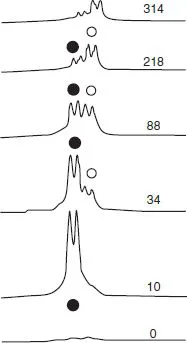

Figure 1.3 Methyl region as a function of time (minutes) of the 1H NMR spectrum from the rearrangement of RhD(CH3)(Tp′)(CNCH2But), to RhH(CH2D)(Tp′)(CNCH2But) in benzene-d6 at 295 K [3].

Figure 1.4 133Cs NMR spectra of human erythrocytes suspended in a buffer containing 140 mM NaCl and 10 mM CsCl. The origin of the chemical shift scale is arbitrary [4, 5].

In addition to chemical shifts, the observed signal multiplicity (as in Figures 1.2 and 1.3) can be useful, as the observation of a coupling constant (J-value) can help to confirm that a fragment is within the coordination sphere. In Figure 1.2, an acetate carbon is coupled to the 31P. In Figure 1.3, the 103Rh (I = 1/2, 100% natural abundance) couples to the 1H of the methyl group. Apart from these routine parameters, organometallic chemists need to occasionally use slightly more specialized NMR tools. Spin–lattice relaxation times, T1’s, for example, are now used to characterize metal molecular hydrogen complexes. All these, and others, together with the ability to detect and measure solution dynamics over several orders of magnitude, contribute to making NMR an indispensable technique. However, modern NMR spectrometers are not always simple to use and obtaining good quality NMR spectra can require some effort.

References

1. Helfer, D.S. and Atwood, J.D. (2002) Organometallics, 21, 250.

2. Geldbach, T.J., den Reijer, C.J., Worle, M., and Pregosin, P.S. (2002) Inorg. Chim. Acta, 330, 155.

3. Wick, D.D., Reynolds, K.A., and Jones, W.D. (1999) J. Am. Chem. Soc., 121, 3974.

4. Davis, D.G., Murphy, E., and London, R.E. (1988) Biochemistry, 27, 3547.

5. Ronconi, L. and Sadler, P.J. (2008) Coord. Chem. Rev., 252, 2239.

1) Although not always specified, the 13C and 31P NMR spectra that follow throughout this text (and in the literature) are almost always measured with broad band 1H decoupling, so that nJ(1H,X) coupling constants are not present and this helps to simplify the spectra. Occasionally, this will be indicated as “13C(1H)” or “31P{1H}.” Unless otherwise specified, the reader should assume broad-band proton decoupling.

2

Routine Measuring and Relaxation

2.1 Getting Started

Preparing the sample may not be trivial (many organometallic complexes are air and water sensitive); but assuming that one has prepared circa 0.7 ml of a clear solution containing 5–10mg of sample,1) in the usual 5 mm NMR tube, one is ready to measure a spectrum.

Most beginning researchers place the sample in the magnet, stabilize the magnetic field via a 2H lock (frequently no longer necessary), call up a simple measuring program, and type, “go.” For a standard one-dimensional proton 1H NMR measurement, a few minutes (or less) of accumulation time are often sufficient to obtain a 1H free induction decay (FID) that, after Fourier transformation, affords a spectrum with sufficient signal-to-noise (S/N) ratio. After a phase correction, the spectrum is plotted.2)

Typically, these operations are followed by an integration procedure to determine the relative number of protons in the various groupings of resonances, and this may be where a problem arises. The integration obtained may indicate that, instead of, for example, a 2 : 1 ratio, one finds a 1.7 : 1 ratio or 2.3 : 1 ratio. There may be a structural reason for the observed results, but sometimes, the problem is simply one of “relaxation.”

The NMR program may already contain a “recommended” 1H pulse length (or it may simply be what the last researcher found to be optimal for his or her chemistry). If the chosen pulse length and/or the acquisition time (the time used by the computer to collect the FID) have not ...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Contents

- Series Title

- Title Page

- The Author

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 Routine Measuring and Relaxation

- 3 COSY and HMQC 2-D Sequences

- 4 Overhauser Effects and 2-D NOESY

- 5 Diffusion Constants via NMR Measurements

- 6 Chemical Shifts

- 7 Coupling Constants

- 8 Dynamics

- 9 Preface to the Problems

- 10 Organometallic Introduction

- 11 NMR Problems

- 12 Solutions to the Problems and Comments

- Index