![]()

Chapter 1

Network Coding: From Theory to Practice 1

1.1. Introduction

Traditionally in a network, the intermediate nodes intervening in the routing of the information flow between a source node and a destination node transmit data packets without processing them. Network coding is an approach that allows the intermediate nodes to mix or combine the packets between them to improve the network performances. These performances depend on the number of packets to be combined, on the way they are combined with each other, and on the information the node must have on its network topology and state to perform the right coding.

Network coding was initially a purely theoretical approach because it required that the coding scenario be centralized and that the existing flows were known in advance. Its evolution has enabled us to use random parameters and thus to make it distributed and applicable in practice.

Network coding improves the network performances in terms of throughput because its use makes it possible to reach the maximum capacity of the network, i.e. max-flow min-cut. Furthermore, it is robust to losses. In fact, the loss of a packet has less impact on the performances because the information it contains can be recovered from other combined packets. It is also scalable because it is decentralized and uses local information for the collaboration between nodes. Finally, it enables an increased security because a combined packet is only readable provided that all the packets used to make the combination are available.

All these advantages allow network coding to be used in various network topologies (wired, cellular, ad hoc, etc.) and for different applications (peer-to-peer, TCP, applications with quality of service (QoS), etc.).

In this chapter, we explain the theoretical aspect of network coding, its principle and the advantage of using it, and then we give examples of its practical applications.

1.2. Theoretical approach

In information theory, the concept of network coding was introduced for the first time by [AHL 00]. The main idea behind this concept is that instead of considering the node as a simple information flow relay, network coding allows the node to combine several packets into a single packet. The history of network coding is presented in detail in [NET 00].

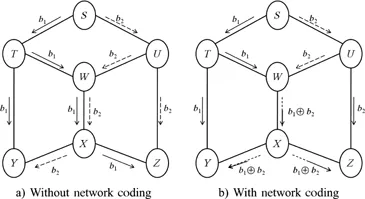

We explain the working of network coding with the example of the wired butterfly network illustrated in Figure 1.1.

Source node S wants to send two bits b1 and b2 to destinations Y and Z (multicast). For this, S sends b1 to T and b2 to U. Then, T sends b1 to W and Y . Similarly, U sends b2 to W and Z. In a conventional scenario, i.e. without network coding, and by assuming that all the links have a unit capacity, W sends b1 then b2 (or vice versa) to X. Then, X sends b1 to Z and b2 to Y.

By using network coding, W performs a combination of two bits, an exclusive OR, for instance, and sends it to X. Then, X transmits this combination to Y and Z. Node Y (respectively Z) receives b1 and b1 ⊕ b2 (respectively, b2 and b1 ⊕ b2) and can consequently recover b2 (respectively b1) by performing the operation b1 ⊕ (b1 ⊕ b2) (respectively, b2 ⊕ (b1 ⊕ b2)).

We can easily infer that the conventional approach requires ten transmissions, while the approach using network coding requires nine. The coding gain is then 10/9 in the wired network.

If we consider a wireless butterfly network, each transmission is being received by all the neighbors of the emitting node, and the gain would be 8/6. Here we notice that network coding has more significant impact in a wireless environment.

This section thus explains the theoretical aspects of network coding and its evolution, from its advantage in terms of maximum capacity to its use of random values allowing it to be scalable and put into practice.

1.2.1. Max-flow min-cut

Generally, the quantity of information circulating in a communication network cannot exceed a given value, which is set by the maximum capacity reachable in this network. This capacity is defined by the max-flow min-cut principle. The use of network coding enables us to reach this maximum capacity.

In graph theory, the max-flow min-cut problem consists of finding a maximum flow that can be carried out from a source toward a destination. In a network, this amounts to finding the paths that the data sent by the source must follow to have the maximum flow capacity. For instance, in the butterfly network illustrated in Figure 1.1, by assuming unit capacity links and by considering source S and destination Y, S can send at most two pieces of data to Y via S → T → Y and S → U → W → X → Y. In this case, the capacity as defined in max-flow min-cut between S and Y has a value of 2 (equivalent to the number of independent paths linking the source to its destination in the case of unit capacities). Similarly, the max-flow min-cut capacity between S and Z, independent of the flow from S to Y , is equal to 2.

Let us now assume that source S wants to send two pieces of data to two destinations Y and Z. The maximum reachable capacity is equal to the smallest of the maximum capacities for each of the destinations taken separately. This capacity is thus equal to 2. However, without network coding, the unit capacity of the W → X link does not enable us to simultaneously route the data of the multicast flow coming from nodes T and U. Thus the maximum reachable capacity of S toward its destinations cannot be reached, except by doubling the capacity of the W → X link.

On the other hand, the use of network coding enables the sending of a data combination on the W → X link of unit capacity, making it possible to simultaneously route data toward the destinations and hence to reach the maximum capacity equal to 2.

In what follows, we are interested in the feasibility of a communication scenario implementing network coding and enabling us to reach the max-flow min-cut bound.

1.2.2. Admissible code

In [AHL 00], the authors introduce the concept of network coding and give a characterization of the admissible coding rate.

The capacity of the graph links is said to be admissible if and only if the information rate from the source is smaller than or equal to the max-flow min-cut value obtained with this capacity. A coding scheme fulfilling an admissible capacity is said to be an admissible code. Moreover, an α-code is represented by a transaction sequence that describes a communication scenario. Each transaction transfers a piece of information (data combination previously received) from the sender to one or several receivers. An α-code is said to be α-admissible if this transaction scenario exists.

The main contribution of [AHL 00] is to prove that the set of admissible codes corresponds to the set of α-admissible codes. In other words, for networks wishing for traffic with a capacity lower than or equal to that of max-flow min-cut, there exists an α-admissible code, using in particular network coding, which is associated there with. The proof is done for a source node in a cyclic or acyclic graph.

For multiple sources, if two information sources are independent, the solution is obtained by solving each problem individually (superposition principle). However, the solution is not optimal, in general. We see different coding techniques in the following section.

1.2.3. Linear code

There exist diverse methods to combine the packets. It has been shown in [LI 03] that for multicast traffic, the linear code multicasts (LCM) are sufficient to reach the limits of maximum capacity. The use of an LCM makes the coding/decoding process easier and faster to implement in practice [YEU 06].

A linear combination is a sum of packets weighted by coefficients. The assignment of coefficients can be carried out in several ways. For instance, a greedy algorithm has been proposed in [LI 03] for the code construction. The following sections present less complex coding techniques.

1.2.4. Algebraic resolution

The coding of packets to be combined allowing us to reach the maximum capacity is not unique. The authors of [KOE 03] propose to solve the network coding problem algebraically. They give necessary and sufficient conditions under which a set of connections is feasible in a network. In the multicast case, a connection transfers the data (stochastic process) from the source node to several destination nodes. In Figure 1.2, for example, node a sends three data units to node d. The transfer matrix having X as input and Z as output is ...