- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Biosensor Nanomaterials

About this book

Biosensors are devices that detect the presence of microbials such as bacteria, viruses or a range biomolecules, including proteins, enzymes, DNA and RNA. For example, they are routinely applied for monitoring the glucose concentration in blood, quality analysis of fresh and waste water and for food control. Nanomaterials are ideal candidates for building sensor devces: where in just a few molecules can alter the properties so drastically that these changes may be easily detected by optical, electrical or chemical means. Recent advantages have radically increased the sensitivity of nanomaterial-based biosensors, making it possible to detect one particular molecule against a background of billions of others.

Focusing on the materials suitable for biosensor applications, such as nanoparticles, quantum dots, meso- and nanoporous materials and nanotbues, this text enables the reader to prepare the respective nanomaterials for use in actual devices by appropriate functionalization, surface processing or directed self-assembly. The emphasis throughout is on electrochemical, optical and mechancial detection methods, leading to solutions for today's most challenging tasks.

The result is a reference for researchers and developers, disseminating first-hand information on which nanomaterial is best suited to a particular application - and why.

Focusing on the materials suitable for biosensor applications, such as nanoparticles, quantum dots, meso- and nanoporous materials and nanotbues, this text enables the reader to prepare the respective nanomaterials for use in actual devices by appropriate functionalization, surface processing or directed self-assembly. The emphasis throughout is on electrochemical, optical and mechancial detection methods, leading to solutions for today's most challenging tasks.

The result is a reference for researchers and developers, disseminating first-hand information on which nanomaterial is best suited to a particular application - and why.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

New Micro- and Nanotechnologies for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

1.1 Introduction

Over the last decade, great attention has been paid to the inclusion of newly developed nanomaterials such as nanowires, nanotubes, and nanocrystals in sensor devices. This can be attributed to the ability to tailor the size and structure, and hence the properties of nanomaterials, thus opening up excellent prospects for designing novel sensing systems and enhancing the performance of bioanalytical assays [1]. Considering that most biological systems, including viruses, membranes, and protein complexes, are naturally nanostructured materials and that molecular interactions take place on a nanometer scale, nanomaterials are intuitive candidates for integration into biomedical and bioanalytical devices [2, 3]. Moreover, they can pave the way for the miniaturization of sensors and devices with nanometer dimensions (nanosensors and nanobiosensors) in order to obtain better sensitivity, specificity, and faster rates of recognition compared to current solutions.

The chemical, electronic, and optical properties of nanomaterials generally depend on both their dimensions and their morphology [4]. A wide variety of nanostructures have been reported in the literature for interesting analytical applications. Among these, organic and inorganic nanotubes, nanoparticles, and metal oxide nanowires have provided promising building blocks for the realization of nanoscale electrochemical biosensors due to their biocompatibility and technologically important combination of properties, such as high surface area, good electrical properties, and chemical stability. Moreover, the integration of nanomaterials in electrochemical devices offers the possibility of realizing portable, easy-to-use, and inexpensive sensors, due to the ease of miniaturization of both the material and the transduction system. Over the last decade, this field has been extensively investigated and a huge number of papers have been published. This chapter principally summarizes progress made in the last few years (2005 to date) in the integration of nanomaterials such as carbon nanotubes (CNTs), nanoparticles, and polymer nanostructures in electrochemical biosensing systems.

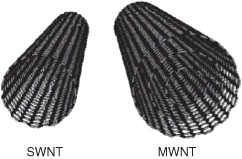

Since their discovery in 1991 [5], CNTs have generated great interest for possible applications in electrochemical devices [6–8]. CNTs are fullerene-like structures (Figure 1.1) that can be single-walled (SWNTs) or multiwalled (MWNTs) [9]. SWNTs are cylindrical graphite sheets of 0.5–1 nm diameter capped by hemispherical ends, while MWNTs comprise several concentric cylinders of these graphitic shells with a layer spacing of 0.3–0.4 nm. MWNTs tend to have diameters in the range 2–100 nm. CNTs can be produced by arc-discharge methods [10], laser ablation [11], or chemical vapor deposition (CVD) [12], which has the advantage of allowing the control of the location and alignment of synthesized nanostructures.

Figure 1.1 Schematic representations of a SWNT and a MWNT

(http://www-ibmc.u- strasbg.fr/ict/vectorisation/nanotubes_eng.shtml).

In a SWNT every atom is on the surface and exposed to the environment. Moreover, charge transfer or small changes in the charge environment of a nanotube can cause drastic changes to its electrical properties. The electrocatalytic activity of CNTs has been related to the “topological defects” characteristic of their particular structure; the presence of pentagonal domains in the hemispherical ends or in defects along the graphite cylinder produces regions with charge density higher than in the regular hexagonal network, thus increasing the electroactivity of CNTs [8, 13, 14]. For these reasons they have found wide application as electrode materials and a huge number of electrochemical biosensors have been described employing CNTs as a platform for biomolecule immobilization as well as for electrochemical transduction. The only limitation can be their highly stable and closed structure, which does not allow a high degree of functionalization [15]. Adsorption or covalent immobilization can only be achieved at the open end of functionalized nanotubes, after a proper oxidative pretreatment [16].

Another class of organic nanomaterials that, compared to CNTs, allows easier chemical modification is conductive polymer nanostructures. Conducting polymers are multifunctional materials that can be employed as receptors as well as transducers or immobilization matrices in electrochemical biosensing. They are characterized by an extended π-conjugation along the polymer backbone, which promotes an intrinsic conductivity, ranging between 10−14 and 102 S cm−1 [17]. Their electrical conductivity results from the formation of charge carriers (“doping”) upon oxidizing (p-doping) or reducing (n-doping) their conjugated backbone [18]. In this way they assume the electrical properties of metals, while having the characteristics of organic polymers, such as light weight, resistance to corrosion, flexibility, and ease of fabrication [19]. When formed as nanostructures, conductive polymers assume further appealing properties: ease of preparation by chemical or electrochemical methods, sensitivity towards a wide range of analytes, considerable signal amplification due to their electrical conductivity, and fast electron transfer rate. Moreover, they allow easy chemical functionalization of their structure in order to obtain high specificity towards different compounds, and are amenable to fabrication procedures that greatly facilitate miniaturization and array production [20].

Nanostructured conductive polymers can be obtained by “template” or “template-free” methods of synthesis, as widely reviewed [21–25]. “Template” synthesis involves the employment of physical templates, such as fibers or membranes (hard templates), or chemical template processes (soft templates), such as emulsion with surfactants, interfacial polymerization, radiolytic synthesis, sonochemical and rapid mixing reaction methods, liquid crystals, and biomolecules [25].One of the most versatile classes of nanomaterials is the nanoparticle. Depending on their composition (metal, semiconductor, magnetic), nanosize particles (or beads) exemplify different functions in electroanayltical applications. Metal nanoparticles provide three main functions: enhancement of electrical contact between biomolecules and electrode surface, catalytic effects, and, together with semiconductor ones, labeling and signal amplification [26]. They are typically obtained by chemical reduction of corresponding transition metal salts in the presence of a stabilizer (self-assembled monolayers, microemulsions, polymers matrixes), which give the surface stability and proper functionalization, in order to modulate charge and solubility properties [27]. Among them, the most widely used have been gold nanoparticles (Au-NPs) because of their unique biocompatibility, structural, electronic, and catalytic properties.

Magnetic particles act mainly as functional components for immobilization of biomolecules, separation, and delivery of reactants. The magnetic core–shell is commonly constituted by iron oxides, obtained by coprecipitation of Fe(II) and Fe(III) aqueous salts by addition of a base. Upon modulating synthetic parameters, it is possible to obtain the required characteristics for biomedical and bioengineering applications, such as uniform size (smaller than 100 nm), specific physical and chemical properties, and high magnetization [28]. Moreover, with proper surface coating, biomodification and biocompatibility can be achieved.

The next three sections are dedicated to illustrating the most interesting applications of each class of these materials for the realization of catalytic as well as affinity electrochemical biosensors.

1.2 Carbon Nanotubes

Different types of devices have been reported depending on the CNT electrode constitution, bioreceptor employed (enzymes, antibodies, DNA), and immobilization strategy (covalent, noncovalent). The majority of them have been obtained by modifying carbon electrode surfaces (mainly glassy carbon (GC) or carbon paste) with a dispersion of CNTs in polymers or solvents, thus increasing the sensitivity of the analysis by orders of magnitude with respect to the bare electrode surface. Solvents like dimethylformamide (DMF), ethanol, or polymeric compounds like chitosan and Nafion are the most used dispersion matrices for this kind of process. Moreover, further advantages have been demonstrated to derive from the employment of electrode surfaces based on highly ordered and vertically aligned CNTs.

1.2.1 Carbon Nanotubes Used in Catalytic Biosensors

Many CNT-based enzymatic biosensors have been reported for the determination of various biochemicals (e.g., glucose, cholesterol, etc.) and environmental pollutants (e.g., organophosphate pesticides). A simple solution was achieved by Carpani et al. [29] by dispersing SWNTs in DMF with the aid of ultrasonication and dropping the suspension directly onto the electrochemically activated surface of GC electrodes. Glucose oxidase (GOx) was immobilized by treatment with glutaraldehyde as a cross-linker, both on bare GC- and SWNT-modified electrodes, and the response of the two types of sensor to glucose was evaluated. The SWNT/GC/GOx electrodes exhibited a more sensitive response, due to the enhanced electron transfer rate in the presence of CNTs. However, GC/GOx electrodes exhibited a lower background current, giving rise to a better signal to noise ratio.

Radoi et al. [30] modified carbon screen-printed electrodes (SPEs) with a suspension of SWNTs in ethanol. The nanotubes had been previously oxidized in a strong acid environment to generate carboxyl groups and covalently functionalized with Variamine blue, a redox mediator, by the carbodiimide conjugation method. The sensor was tested for the detection of nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NADH) by flow-injection analysis and the resulting catalytic activity was higher than that obtained using an unmodified SPE. Thus, nanostructured sensors were subsequently employed in NAD+-dependent biosensors (i.e., for lactate detection). Upon detecting similar analytes, Gorton’s group [31] reported an interesting study of the sensitivity-enhancing effect of SWNTs in amperometric biosensing, which depended on their average length distribution. They modified carbon electrodes with the enzyme diaphorase (which catalyzes the oxidation of NADH to NAD+) and SWNTs using an osmium redox polymer hydrogel, then tested the sensor response towards NADH by varying the length of the nanotubes. Surprisingly, the best performance was achieved using SWNTs of medium length. The proposed explanation was a sensitivity-increasing effect caused mainly by the structural and electrical properties of the SWNTs, which have an optimum length (mainly depending on the type of redox enzymes) that allows both efficient blending and charge transport over large distances.

Jeykumari and Narayanan [32] developed a glucose biosensor based on the combination of the biocatalytic activity of GOx with the electrocatalytic properties of CNTs and the redox mediator Neutral red for the determination of glucose. MWNTs were functionalized with the mediator through the carbodiimide reaction, and mixed with GOx and Nafion as a binder. The suspension was finally deposited on paraffin-impregnated graphite electrodes. The MWNT/Neutral red/GOx/Nafion nanobiocomposite film combined the advantages of the electrocatalytic activity of MWNTs with the capability of the composite material to decrease the electrochemical potential required. In this way the response to interfering substrates such as urea, glycine, ascorbic acid, and paracetamol became insignificant. In 2009, the same group [33] proposed an interesting approach to low-level glucose detection by creating a bienzyme-based biosensor. MWNTs were oxidized, functionalized with the redox mediator Toluidine blue, and grafted with GOx and horseradish peroxidase (HRP). These functionalized MWNTs were dissolved in a Nafion matrix and deposited on GC electrodes. In this way glucose reacts with GOx, in the presence of the natural cosubstrate O2, to produce H2O2. H2O2, then, serves as substrate for HRP, which is converted to oxidized form by the redox mediator immobilized on MWNTs. The proximity of a mediator that transfers electrons between the enzyme and the electrode reduced the problem of interferences by other electroactive species. Moreover, the use of multiple enzymes enhanced sensor selectivity and chemically amplified the sensor response.

Another amperometric CNT/Nafion composite was developed by Tsai and Chiu [34] for the determination of phenolic compounds. MWNTs were dispersed within the Nafion matrix together with the enzyme tyrosinase and deposited on GC electrodes. In this way, MWNTs act as efficient conduits for electrons transfer, Nafion is an electrochemical promoting polymeric binder and tyrosinase is the biological catalyst that facilitates the translation of phenols into o-quinones, which can be electrochemically reduced to catechol without any mediator on an electrode surface. The MWNT/Nafion/tyrosinase nanobiocomposite-modified GC electrode exhibited a 3-fold higher sensitive response with respect to the Nafion/tyrosinase biocomposite-modified electrode, due to the inclusion of MWNTs within Nafion/tyrosinase matrices and the amperometric response was proportional to the concentration of several phenolic compounds in the analytically important micromolar range. A similar format had been previously developed by Deo et al. [35] in 2005, by casting with Nafion organophosphorus hydrolase on a CNT-modified transducer. Since the electrochemical reactivity of CNTs is strongly dependent upon their structure and preparation process, an interesting comparison between arc-produced MWNT and CVD-synthesized MWNT- and SWNT-modified electrodes was shown. By comparing their response towards p-nitrophenol, both the SW- and MW-CVD-CNT-coated surfaces exhibited a dramatic enhancement of the sensitivity compared to the arc-produced CNT and bare electrodes. The higher sensitivity of the CVD-CNT-modified electrode reflects a higher density of edge-plane-like defects that lead to higher electrochemical reactivity than previously found [8, 13, 14].

A better way to control the thickness of CNT/polymer films was described by Luo et al. [36], who reported a simple and controllable method for the modification of gold electrodes with a chitosan/CNT nanocomposite through electrodeposition. Compared to other solvents, chitosan can prevent biological molecules from denaturing and its primary amines fac...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- 1 New Micro- and Nanotechnologies for Electrochemical Biosensor Development

- 2 Advanced Nanoparticles in Medical Biosensors

- 3 Smart Polymeric Nanofibers Resolving Biorecognition Issues

- 4 Fabrication and Evaluation of Nanoparticle-Based Biosensors

- 5 Enzyme-Based Biosensors: Synthesis and Applications

- 6 Energy Harvesting for Biosensors Using Biofriendly Materials

- 7 Carbon Nanotubes: In Vitro and In Vivo Sensing and Imaging

- 8 Lipid Nanoparticle-Mediated Detection of Proteins

- 9 Nanomaterials for Optical Imaging

- 10 Semiconductor Quantum Dots for Electrochemical Biosensors

- 11 Functionalized Graphene for Biosensing Applications

- 12 Current Frontiers in Electrochemical Biosensors Using Chitosan Nanocomposites

- 13 Nanomaterials as Promising DNA Biosensors

- 14 Nanocomposites and their Biosensor Applications

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Biosensor Nanomaterials by Songjun Li,Jagdish Singh,He Li,Ipsita A. Banerjee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Materials Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.