![]()

1

Triage and Assessment of the Emergency Patient

Introduction

Throughout the management of the emergency patient a successful outcome is more likely to be achieved where prompt, appropriate action is taken as dictated by the clinical findings of observation and examination. Nowhere is this more important than on initial presentation where the patient with a life-threatening condition must be identified and receive immediate attention; this process is triage.

Triage is a system of rapidly evaluating patients and allocating treatment to those patients that are in most urgent need, or in the case of one individual case, allocating treatment to the most serious problem first. To gain this information, a rapid, efficient, clinical examination of the major body systems is carried out: respiratory, cardiovascular and central nervous system (CNS). The initial examination of each body system should concentrate on a small number of clinical signs that provide the most important information.

In human medicine, triage is well established and used in busy accident and emergency departments or at the scene of major incidents. The same principles apply in veterinary medicine, whether in a dedicated emergency out-of-hours practice or when dealing with an urgent case in a first opinion practice.

Telephone Triage

In many cases the initial contact from the owner of the emergency case will be by telephone. The veterinary nurse is often involved in establishing the urgency of the problem, and vitally whether the animal needs to attend the clinic immediately. From conversation with some owners it will become immediately obvious from the clinical signs described that the case is an emergency and should be seen as soon as possible (see Table 1.1). In other cases the nurse will need to try to determine the nature of the problem, and give advice accordingly. It may be necessary to calm the owner to elicit a concise, relevant history, and caution should be used when assessing an owner’s perception of the patient’s problem. If there is any doubt about the need to see an animal, it is safest to advise the owner to attend or for a veterinary surgeon to discuss the case with the owner. It is advisable that all patients with a traumatic injury should attend the clinic immediately.

Table 1.1 Examples of owner-reported clinical signs that warrant immediate attendance at clinic

- Respiratory distress

- Severe coughing

- Weakness or collapse

- Neurological abnormalities

- Ataxia

- Non-weight-bearing lameness

- Severe pain

| - Abdominal distension

- Persistent vomiting or diarrhoea

- Inability to urinate

- Bleeding from body orifices

- Profuse bleeding from wounds

- Ingestion of toxins

- Dystocia

|

The owner should be questioned as to the signalment of the patient (breed, age, sex and approximate weight) and given clear and concise directions as to where they are to attend (this is especially important where phone lines are diverted out of hours and owners maybe unaware their call has been diverted to another site or clinic) and an estimated time of arrival obtained.

Advice may need to be given on transportation of the animal, especially following trauma. If an animal is unable to walk it may need to be carried; it is preferable for a trauma victim to be carried on a board or something rigid, rather than a blanket (see Figure 1.1). In the case of active bleeding, direct pressure on to a clean cloth is safer than the owner applying a tourniquet. Always warn the owner that the animal may be aggressive due to pain.

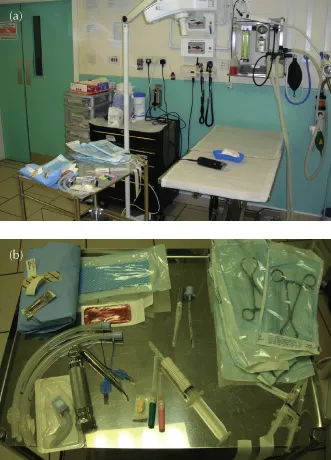

Knowing the nature of the problem, along with the signalment of the animal, allows a great deal of preparation to occur prior to the patient’s arrival (see Figure 1.2); this can save valuable time when initiating stabilisation. For example, equipment for supplementing oxygen or obtaining vascular access can be prepared, or advice can be sought regarding toxic levels, appropriate management and antidotes in cases of intoxication.

Hospital Triage

On arrival at the clinic the major body systems are assessed during the triage, and a brief ‘capsular’ history obtained from the owner (see Table 1.2). See website documents: Triage assessment sheet.

Table 1.2 Questions asked of owners to obtain a ‘capsular history’

- Signalment (age, sex, neutered, breed)

- Vaccination history

| - Duration of presenting complaint

- Current medication

|

During assessment, any abnormality detected with a major body system is likely to be life-threatening; therefore measures are immediately taken to start stabilising that condition, prior to completing the rest of the examination. The aim is not to reach a definitive diagnosis, but to start treatment of life-threatening conditions. So, for example, if an animal is immediately noted to be in respiratory distress, oxygen is administered before any other part of the examination is carried out.

Patients with certain presentations should be taken to the treatment area immediately, regardless of major body system findings (see Table 1.3; Figure 1.3).

Table 1.3 Examples of presenting conditions that should be taken immediately to the treatment area on arrival

- Seizures

- Trauma

- Prolapsed organs

- Dystocia

| - Ingestion of toxins

- Excessive bleeding

- Open fractures

- Burns (see Figure 1.3)

|

A useful path to follow in the initial assessment of major body systems is ABCD, where:

A: Airway

B: Breathing

C: Circulation

D: Dysfunction of the CNS.

A and B: Respiratory System

Emergencies involving the respiratory system require rapid assessment, cautious restraint and prompt measures to start stabilisation. Assessment of the respiratory system should begin as the patient is approached by observing their posture, respiratory effort and pattern, and whether any airway sounds are clearly audible.

In the normal patient, both cats and dogs have a respiratory rate of approximately 10–20 breaths per minute (bpm), ventilation involves very little chest movement, and the chest wall and abdomen move out and in together. Whilst open mouth breathing and panting in a dog is considered normal, the same in a cat is always considered to indicate respiratory distress and oxygen supplementation is indicated.

The respiratory system of the patient is assessed by observation, auscultation and palpation.

Airway

In a collapsed patient, assess if the airway is patent by listening for breathing, and looking in the mouth for any obstruction (blood, vomit, foreign bodies). Facial injuries or cervical bite wounds can interfere with the airway by disrupting the larynx or trachea.

Breathing

Observation

The patient should be closely observed before moving on to auscul...