eBook - ePub

Capitalism and Conservation

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Capitalism and Conservation

About this book

Through a series of case studies from around the world, Capitalism and Conservation presents a critique of conservation's role as a central driver of global capitalism.

- Features innovative new research on case studies on the connections between capitalism and conservation drawn from all over the world

- Examines some of our most popular leisure pursuits and consumption habits to uncover the ways they drive and deepen global capitalism

- Reveals the increase in intensity and variety of forms of capitalist conservation throughout the world

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1

Spectacular Eco-Tour around the Historic Bloc: Theorising the Convergence of Biodiversity Conservation and Capitalist Expansion

Conservation leaders need to stop counting birds and start counting dividends that nature can pay to the people who live in it (Ger Bergkamp, Director, World Water Council1).

Introduction

On 8 October 2008, New York Times business columnist James Kantner wrote:

The World Conservation Congress is abuzz with how the conservation movement will continue to fail to achieve the objectives it has been seeking for decades unless it engages business and embraces business management techniques to further its goals.2

Indeed the Congress projected a strengthening consensus of synergies between growing markets and effective biodiversity conservation. IUCN leadership had recently entered a partnership with Shell Oil, and were busily forging a new one with the Rio Tinto Mining Group.3 The entrance to the Congress was aesthetically dominated by corporate displays, while its theater featured films like “Conservation is Everybody’s Business”. As shocks in the world economy sent ripples of consternation through the Congress, high-profile speakers warned attendees not to view the “implosion of banks and financial institutions” as a “signal to abandon market models” (for details, see MacDonald forthcoming).4

High-profile conservationists, corporate leaders, and celebrities spread the same message to broader publics: capitalism is the key to our ecological future and ecological sustainability will help end our current financial crisis (Igoe forthcoming; Prudham 2009). Through online initiatives, marketing, and fundraising campaigns they not only urge people to support this vision, but also to support re-regulations (cf Castree 2007) of the environment, facilitating the commodification of nature as the solution to problems that threaten our common ecological future (Igoe forthcoming).5 In contrast to Green Marxists’ predictions that the visible and costly environmental contradictions of late capitalism would prompt alliances of environmentalists and workers to demand green socialist alternatives (esp. O’Connor 1988), such initiatives entice consumers to participate in the resolution of capitalism’s environmental contradictions through advocacy, charitable giving and consumption.

Biodiversity conservation figures centrally in these transformations. The economic growth that preceded our current problems coincided with growth in protected areas, including private conservancies (Brockington, Igoe and Duffy 2008). It also accompanied dramatic growth of conservation BINGOs (Big NGOs), as they competed intensively for market shares and brand recognition and dramatically grew their budgets (Chapin 2004; Dowie 2009; MacDonald 2008; Rodriguez et al 2007; Sachedina this volume). Corporations donated millions of dollars to BINGOs and corporate representatives joined their boards (Chapin 2004; Dorsey 2005; Dowie 1995; MacDonald 2008), while conservationists sought to extend their influence inside of corporations.6 Diverse social scientists working in areas targeted for conservation began to observe, in different locations, that partnerships between conservation and capitalism were reshaping nature and society in ways that produced new types of value for capitalist expansion and accumulation (Brockington, Duffy and Igoe 2008; Brockington and Scholfield this volume; Garland 2008; Goldman 2005; Neves this volume; West and Carrier 2004).

Such value production is not limited to specific conservation landscapes. As Garland (2008:52) has noted, conservation as a mode of production appropriates value from landscapes by “transforming it into capital with the capacity to circulate and generate further value at the global level”. This includes images and narratives that circulate widely in the entertainment industry (Brockington 2009; Vivanco 2002), as well as in the marketing of new consumer goods and NGO fundraising (Brockington, Duffy and Igoe 2008; Brockington and Scholfield this volume; Garland 2008; Igoe forthcoming; Sachedina 2008). These also provide essential fodder for powerful discursive claims that markets, information technology, and expert know-how offer new possibilities of optimizing the ecological and economic functions of our planet, simultaneously allowing economic growth to continue while spreading benefits to impoverished rural communities (Luke 1997; Goldman 2008; Igoe forthcoming; McAfee 1999; Neves this volume).

These claims are not always as verifiable, or indeed as common-sensical, as their advocates appear to believe. Moreover, they are often buttressed by overly simplistic presentations of socio-environmental problems and relationships in the capitalist economy (Brockington, Duffy and Igoe 2008:ch 9). Much of the power of these ideas is derived from a currently dominant ideological context where it is believed that the attribution of economic value to nature and its submission to “free market” processes is key to successful conservation. The details of this logic are as follows. Once the value of particular ecosystem is revealed, for example an ecosystem’s ability to store carbon, the ecosystem acquires economic value as a service provider or as a non-consumptive resource, as in the case of eco-tourism. The ecosystem thus putatively becomes a source of income for local communities, creating further capitalist-development opportunities (Sullivan 2009).7 Given that within the tenets of capitalist principles the allocation of funds is directly related to associated potential returns on investment, conservationists who seek donor funds are increasingly under pressure to show the economic advantages of their conservation goals. Hence, the notion that the relationships between conservationist action and capitalist reality are necessarily beneficial becomes increasingly taken-for-granted. This idea becomes hegemonic when it is so systematically and extensively promoted that it acquires the appearance of being the only feasible view of how best to pursue and implement conservation goals. Alternative and critical views of this logic are consistently kept at the margins or outright silenced.

The hegemonic nature of these claims, and the ideological context from which they are derived, present major obstacles to democratic and reflexive discussions of our most pressing socio-environmental problems. Capitalism’s destructive-extractive relationships with the environment are unlikely to be challenged unless we are able to understand the fundamental contradictions between capitalism’s need to expand exponentially vis-à-vis the capacity of ecosystems to withstand and absorb the disturbances and stresses that this exponential growth entails. Indeed, it appears that capitalism is turning the environmental problems it creates into opportunities for further commodification and market expansion (Brockington, Duffy and Igoe 2008; Klein 2007).

The relationship between conservation and capitalism thus presents a salient site of enquiry for documenting and analyzing the kinds of relationships that facilitate capitalism’s ability to reinvent itself even when its excesses appear to threaten the viability of the very ecosystems on which human economic activity depends. We thus propose a theoretical framework from which we can begin to organize our investigations and analyses of these issues. We now turn to a brief outline of this framework and its theoretical antecedents.

The Sustainable Development Historic Bloc and the Spectacle of Nature

Our theoretical framework builds on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony, which he developed in response to his discontent with monolithic and dualistic understandings of domination. Like Gramsci, we are concerned with the ways in which the ideas and agendas of particular interest groups are promoted and imposed over a world of diversity, full of conflicting values and interests. Gramsci (1971b:210–218) was especially fascinated that these processes occurred mostly without recourse to force, but rather through “the manufacture of consent” (1971a:12).

In thinking about global conservation, therefore, we are interested in understanding how such a complex and heterogeneous movement appears to be dominated by a relatively narrow set of values, ideas and institutional agendas. Here we are referring to what Brockington, Duffy and Igoe (2008:9) have labeled “mainstream conservation”, which they describe as the dominant strain of global conservation. The ideas and values of mainstream conservation are most clearly visible in the operations of conservation BINGOs, which dominate conservation funding along with the discursive and spectacular representations of the values and goals of global conservation.

Fully to appreciate the power and influence of mainstream conservation, it is necessary to illuminate its larger context. This in turn refers us to another Gramscian concept; the historic bloc. The historic bloc refers to a historic period in which groups who share particular interests come together to form a distinctly dominant class. The ideas and agendas of this class thus come to permeate an entire society’s understanding of the world.8 Two aspects of the Gramscian notion of historic bloc are germane to the issues that concern us here. First, the ideologies accompanying a particular historic bloc conceal the nature of existing relations of production by presenting a naturalized view of extractive class hierarchies that comprise these relations. Second this concealment has the effect of smoothing over the contradictions, paradoxes and irreconcilable differences that exist within these relations (Gramsci 2000a).

According to Sklair (2001:8) our present historic moment is dominated by “the sustainable development historic bloc”, which purports to offer easy consumption-based solutions to the environmental crises inherent in late market capitalism. They thus present a comforting alternative to the more disruptive social transformations predicted by O’Connor (1988) and other green Marxists. This historic bloc, according to Sklair, is produced and supported by a “transnational capitalist class” of corporate executives, bureaucrats and politicians, professionals, merchants and the mass media. Through their efforts, consumption and spending become indispensable to the solution of environmental problems (Sklair 2001:216).

Mainstream conservation’s connections to this larger historic bloc have their roots in networks and collaborations that were forged in the creation of national parks in the American West at the end of the nineteenth century. This was also America’s “Guilded Age”, which was a period of rapid industrialization, extractive capitalist expansion, and the rise of iconic business tycoons, many of whom also became noted philanthropists. Ironically, these transformations simultaneously threatened the natural beauty of the American West, while producing the elites who championed the cause of protecting that natural beauty. Tsing (2005) aptly notes that, early conservationists pursued strategies that involved the enrolment of these elites in nature conservation and corporate sponsorships for the creation of protected areas (also see Spence 1999). While the contexts of these relationships has changed over time, the creation of American parks has historically entailed the intertwining and blurring of states, private enterprise and philanthropy (eg Fortwangler 2007; Mutchler 2007; Muchnick 2007).

Brockington, Duffy and Igoe (2008:9) refer to the networks and affinities that emerged from these types of processes and relationships as mainstream conservation’s “collaborative legacy”. These networks and affinities, which have become increasingly transnational over time, are evident in the highly visible and central position that philanthropic entities, such as the Rockefeller, Gordon and Betty Moore and the Turner Foundations, have come to occupy in mainstream conservation. Foundations like these and the conservation organizations that they fund, are frequently intertwined by tight networks of interests, values and agendas (Chapin 2004; Grandia forthcoming; Igoe and Fortwangler 2007; MacDonald 2008). They share staff, personnel and board members.9 Moreover, the collaborative legacy forged in the American West continues to extend itself to other parts of the world and incorporate new elites.10

Recent expansions in the collaborative legacy of mainstream...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Introduction: Capitalism and Conservation: The Production and Reproduction of Biodiversity Conservation

- Chapter 1: Spectacular Eco-Tour around the Historic Bloc: Theorising the Convergence of Biodiversity Conservation and Capitalist Expansion

- Chapter 2: The Devil is in the (Bio)diversity: Private Sector “Engagement” and the Restructuring of Biodiversity Conservation

- Chapter 3: The Conservationist Mode of Production and Conservation NGOs in sub-Saharan Africa

- Chapter 4: Shifting Environmental Governance in a Neoliberal World: US AID for Conservation

- Chapter 5: Disconnected Nature: The Scaling Up of AfricanWildlife Foundation and its Impacts on Biodiversity Conservation and Local Livelihoods

- Chapter 6: The Rich, the Powerful and the Endangered: Conservation Elites, Networks and the Dominican Republic

- Chapter 7: Conservative Philanthropists, Royalty and Business Elites in Nature Conservation in Southern Africa

- Chapter 8: Protecting the Environment the NaturalWay: Ethical Consumption and Commodity Fetishism

- Chapter 9: Making the Market: Specialty Coffee, Generational Pitches, and Papua New Guinea

- Chapter 10: Cashing in on Cetourism: A Critical Ecological Engagement with Dominant E-NGO Discourses on Whaling, Cetacean Conservation, and Whale Watching

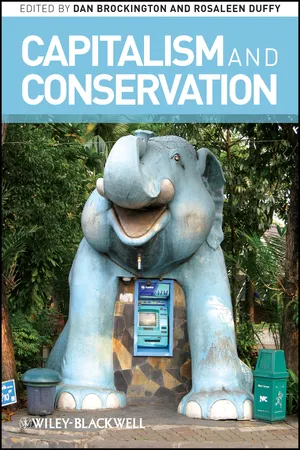

- Chapter 11: Neoliberalising Nature? Elephant-Back Tourism in Thailand and Botswana

- Chapter 12: The Receiving End of Reform: Everyday Responses to Neoliberalisation in Southeastern Mexico

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Capitalism and Conservation by Dan Brockington, Rosaleen Duffy, Dan Brockington,Rosaleen Duffy in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Biological Sciences & Environmental Science. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.