Pediatric Cardiovascular Medicine

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

Pediatric Cardiovascular Medicine

About this book

The first edition of this text, edited by two of the world's most respected pediatric cardiologists, set the standard for a single-volume, clinically focused textbook on this subject. This new edition, revisedand updated by contributors representing today's global thought leaders, offers increasedcoverage of the most important current topics, such as pediatric electrophysiology, congenital heart disease, cardiovascular genetics/genomics, and theidentification and management of risk factors in children, while maintaining the clinical focus. Published with a companion website that features additional images for download, self-assessment questions designed to aid readers who are preparing for examinations, and other features, Pediatric Cardiovascular Medicine, Second Edition, is the perfect reference for residents, fellows, pediatricians, as well as specialists in pediatric cardiology.

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- List of Contributors

- Preface

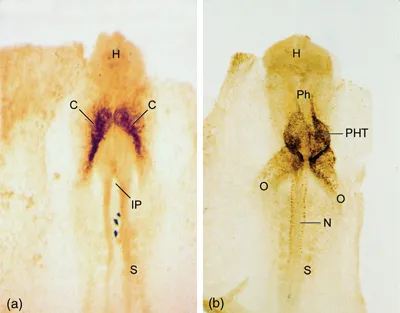

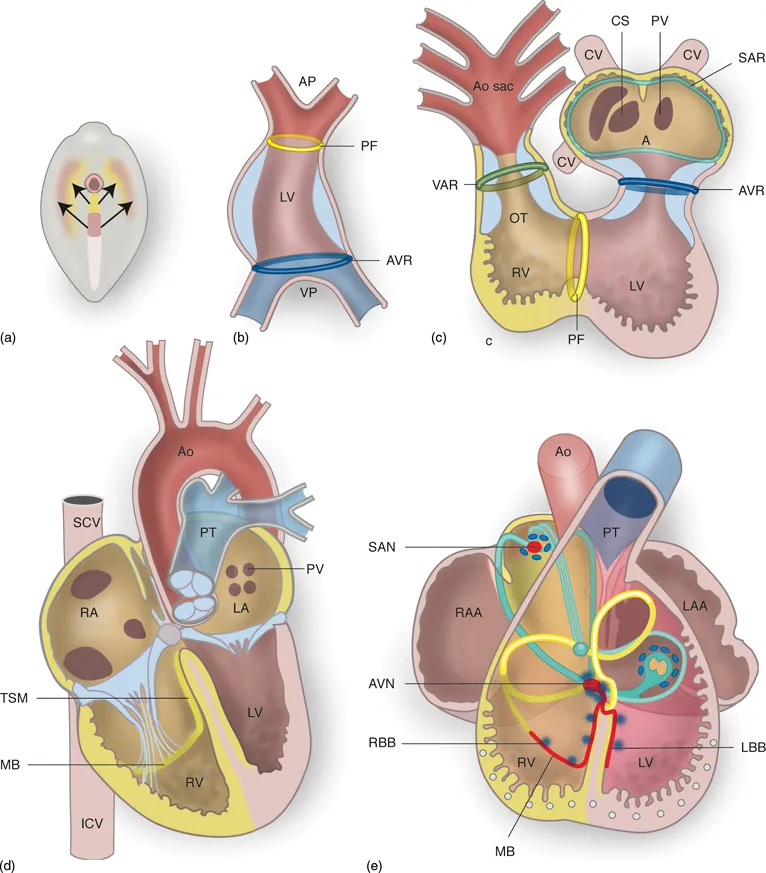

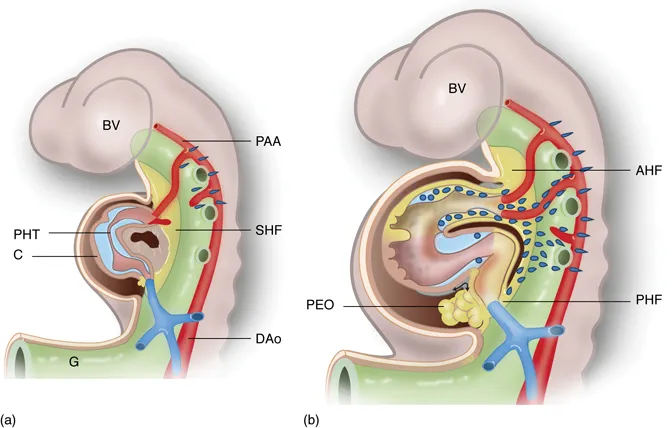

- 1 Normal and Abnormal Cardiac Development

- 2 Genetics of Cardiovascular Disease in the Young

- 3 Developmental Physiology of the Circulation

- 4 Basic Anatomy and Physiology of the Heart, and Coronary and Peripheral Circulations

- 5 Pulmonary Vascular Pathophysiology

- 6 Clinical History and Physical Examination

- 7 Electrocardiography

- 8 Echocardiography

- 9 Radiographic Techniques

- 10 Cardiac Catheterization and Angiography

- 11 Exercise Testing

- 12 Thrombosis in Congenital and Acquired Disease

- 13 Genetic Testing

- 14 Practices in Congenital Cardiac Surgery: Pulmonary Artery Banding, Systemic to Pulmonary Artery Shunting, Cardiopulmonary Bypass, and Mechanical Ventricular Assist Devices

- 15 Postoperative Problems

- 16 Fetal Treatment

- 17 Newborn Diagnosis and Management

- 18 Noncardiac Problems of the Neonatal Period

- 19 The Epidemiology of Cardiovascular Malformations

- 20 Anatomy and Description of the Congenitally Malformed Heart

- 21 Atrial Level Shunts Including Partial Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection and Scimitar Syndrome

- 22 Atrioventricular Septal Defects

- 23 Ventricular Septal Defect

- 24 Aortopulmonary Shunts: Patent Ductus Arteriosus, Aortopulmonary Window, Aortic Origin of a Pulmonary Artery

- 25 Sinus of Valsalva Fistula

- 26 Systemic Arteriovenous Fistula

- 27 Left Ventricular Inflow Obstruction: Pulmonary Vein Stenosis, Cor Triatriatum, Supravalvar Mitral Ring, Mitral Valve Stenosis

- 28 Left Ventricular Inflow Regurgitation

- 29 Right Ventricular Inflow Obstruction

- 30 Left Ventricular Outflow Obstruction: Aortic Valve Stenosis, Subaortic Stenosis, Supravalvar Aortic Stenosis, and Bicuspid Aortic Valve

- 31 Left Ventricular Outflow Regurgitation and Aortoventricular Tunnel

- 32 Coarctation of the Aorta and Interrupted Aortic Arch

- 33 Right Ventricular Outflow Tract Obstruction

- 34 Total Anomalous Pulmonary Venous Connection

- 35 Tricuspid Atresia

- 36 Ebstein Anomaly of the Tricuspid Valve

- 37 Anomalies of the Coronary Sinus

- 38 Hypoplastic Left Heart Syndrome

- 39 Univentricular Heart

- 40 Pulmonary Atresia with Intact Ventricular Septum

- 41 Tetralogy of Fallot and Pulmonary Atresia with Ventricular Septal Defect

- 42 Complete Transposition of the Great Arteries

- 43 Congenitally Corrected Transposition of the Great Arteries

- 44 Transposition and Malposition of the Great Arteries with Ventricular Septal Defects

- 45 Common Arterial Trunk (Truncus Arteriosus)

- 46 Pulmonary Arteriovenous Malformations

- 47 Vascular Rings

- 48 Coronary Arterial Abnormalities and Diseases

- 49 Pulmonary Artery Sling

- 50 Abnormalities of Situs

- 51 Pediatric Pulmonary Hypertension

- 52 Central Nervous System Complications

- 53 Adults with Congenital Heart Disease

- 54 Quality of Life and Psychosocial Functioning in Adults with Congenital Heart Disease

- 55 Cardiac Arrhythmias: Diagnosis and Management

- 56 Syncope

- 57 Cardiovascular Disease, Sudden Cardiac Death, and Preparticipation Screening in Young Competitive Athletes

- 58 Cardiomyopathies

- 59 Pericardial Diseases

- 60 Infective Endocarditis

- 61 Rheumatic Fever

- 62 Rheumatic Heart Disease

- 63 Kawasaki Disease

- 64 Hypertension in Children and Adolescents

- 65 Cardiovascular Risk Factors: Obesity, Diabetes, and Lipids

- 66 Cardiac Tumors

- 67 Connective Tissue Disorders

- 68 Cardiac Involvement in the Mucopolysaccharide Disorders

- 69 Cardiovascular Manifestations of Pediatric Rheumatic Diseases

- 70 Pediatric Heart Transplantation

- 71 Cardiac Failure

- 72 Pediatric Cardiology in the Tropics and Underdeveloped Countries

- Index