eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 2

Applied and Policy Issues

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 2

Applied and Policy Issues

About this book

Now part of a two-volume set, the fully revised and updated second edition of The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 2: Applied and Policy Issues provides comprehensive coverage of the applied and policy issues relating to infant development.

- Updated, fully-revised and expanded, this two-volume set presents in-depth and cutting edge coverage of both basic and applied developmental issues during infancy

- Features contributions by leading international researchers and practitioners in the field that reflect the most current theories and research findings

- Includes editor commentary and analysis to synthesize the material and provide further insight

- The most comprehensive work available in this dynamic and rapidly growing field

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 2 by J. Gavin Bremner, Theodore D. Wachs, J. Gavin Bremner,Theodore D. Wachs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Developmental Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART I

Bioecological Risks

Introduction

The four chapters in this part of the book detail the nature and consequences of infant exposure to pre- or postnatal bioecological risk factors, which have the potential to compromise both early and later developmental outcomes. Chapter 1 by deRegnier and Desai on fetal development begins with a description of normal brain development during the prenatal period. The chapter then describes the various influences that can impair normal brain development during this period, including genetic defects, maternal nutritional deficiencies during pregnancy, the impact of fetal exposure to both legal (e.g., antidepressants) and illegal drugs (e.g., cocaine) or environmental toxins, and maternal stress during pregnancy. The chapter concludes with a presentation of recent evidence on the developing functional capacities of the fetus, including auditory processing, learning and memory.

Chapter 2 is by Black and Hurley, and covers the many aspects of infant nutrition, as viewed within the framework of developmental- ecological theory (e.g., Bronfenbrenner). This framework is evident in a number of topics discussed in the chapter such as the problem of infant failure to thrive and the development of child eating patterns. The chapter begins with a discussion of the role of macro- (e.g., protein, calories) and micronutritional deficiencies (e.g., trace minerals, vitamins) and breastfeeding in infant physical growth and cognitive and social- emotional development. Cutting across the nutritional spectrum, Black and Hurley then deal with the relation of parental feeding styles to the development of obesity in infancy, and conclude the chapter with a discussion of public policy contributions to programs designed to promote infant nutrition.

Chapter 3 by Karp focuses on relations between health and illness in infancy and various dimensions of infant development. Topics covered include the postnatal consequences of maternal diabetes during pregnancy, bacterial and viral infections during infancy (including issues centered around vaccination of infants), infant exposure to environmental toxins (e.g., lead), physical injuries, metabolic disease and infant colic. The chapter concludes with a discussion of how issues in infant health must be viewed within a larger social and cultural framework, including the availability of health care.

Chapter 4 by Preisler deals with the developmental consequences for infants who have significant auditory or visual impairments, with specific emphasis on infant –caregiver communication and infant language development. Preisler points out a shift in focus away from a deficit model (what children with sensory impairments cannot do) to a competence model (how children with auditory or visual impairments are able to communicate with their caregivers). Based on this distinction, a large portion of the chapter is dedicated to presenting evidence on the functional communicative capacities of children with sensory impairments. In addition, consideration is given to the impact on parents of having a child with auditory or visual impairment, the fundamental role parents play in helping their sensory impaired child establish communication, and means through which parental caregiving can be facilitated.

1

Fetal Development

Introduction

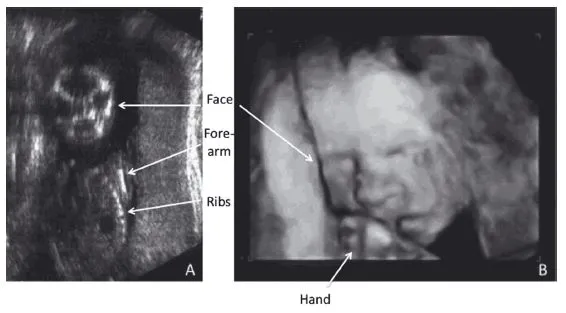

In years past, the study of human development began at birth, as the weeks of gestation were a “black box” and the development of a live fetus in utero was largely invisible to psychologists interested in early development. Fetal anatomic brain development was described by pathologists many years ago and some aspects of hearing and motor development could be inferred by the reports of pregnant women. However, many aspects of the sensory, cognitive, and emotional development of the fetus were unknown. This situation changed dramatically with the advent of fetal ultrasound and heart rate monitoring. First used by obstetricians to evaluate fetal anatomic development (Figure 1.1) and well-being, these techniques have been significantly refined and are now used by psychologists to evaluate fetal responses to external events and to show evidence of fetal learning.

This chapter will review what is currently known about the normal development of the fetal brain, including both the anatomy and function. It will also be important to understand how brain development is affected by genetic problems, nutritional deficiencies, maternal medical problems, and toxins such as alcohol. This chapter also will deliberate the thorny question of whether fetal experiences are important in setting up the basic framework of the brain or whether genetics rules the fetal period, bringing the nature vs. nurture question into a new realm for the twenty-first century.

Anatomic Development

The timetable of a normal, healthy pregnancy begins two weeks after the mother’s last menstrual period. At this time, ovulation occurs as the egg is released from the ovary. The egg can be fertilized within several days of release from the ovary and the process of fetal development begins, culminating with the birth of the baby approximately 38–41 weeks after the mother’s last menstrual period. This time in utero is known as gestation and the age of specific occurrences is known as gestational age.

Figure 1.1 Two-dimensional (A) and three-dimensional (B) ultrasound pictures of the fetus, showing the fetal face (A and B) as well as fetal chest and abdomen (A).

The sperm and the egg contain half the genetic material (chromosomes) of each parent that combines to create a full complement of chromosomes for the new baby. Each set of chromosomes is composed of the sex chromosomes (XX for a girl, XY for a boy) plus 22 pairs of autosomes (nonsex chromosomes). Chromosomal arrangement in the newly fertilized egg is a process that frequently goes astray; approximately 20% of pregnancies end in first trimester miscarriages, and 50% of these are due to abnormal chromosomes (Goddijn & Leschot, 2000). Later miscarriages may also result from fetal chromosomal abnormalities, but some fetuses with less severe chromosomal abnormalities may survive till birth. This is particularly true for infants with trisomy of chromosomes 21, 13, and 18 or monosomy of the X chromosome in a female. In a baby with a trisomy, rather than the pair of chromosomes, there are three chromosomes, whereas in a monosomy, there is only one copy. Chromosomal abnormalities are important as they may result in alterations in the normal trajectory of brain development, resulting in significant differences in central nervous system function (Volpe, 2001).

The anatomy of brain development

Brain development has been traditionally divided into four processes: formation and differentiation of the neural tube; formation and migration of neurons; formation and elaboration of synapses; and myelination. In general, these processes occur sequentially, but there is temporal overlap, particularly between synaptogenesis and myelination (Nelson, 2002).

Formation and differentiation of the neural tube. Formation of the neural tube begins very early in development, at 13–17 days after fertilization, with the development of a neural plate that folds in upon itself, and “zips” closed beginning near the base of the brain at about 22 days, and then proceeding simultaneously up toward the head (cranially) and down toward the base of spine (caudally). Failure of normal neural tube formation in the fetus leads to severe abnormalities; some of these result in stillbirth or early neonatal death (e.g., anencephaly), whereas others lead to the birth of an infant with an abnormal nervous system, such as spina bifida (meningomyelocele).

Differentiation of the brain continues through the second to third month as the neural tube folds on itself and cleaves to form the optic vesicles which will form the eye, olfactory bulbs (for smell) and major parts of the brain, including the cerebral hemispheres, basal ganglia, ventricles, and hypothalamus. In general, abnormal differentiation of the neural tube results in severe neurologic disorders in the fetus, often leading to stillbirth or death during infancy. Surviving infants may suffer from seizure disorders, severe developmental delay, hormonal abnormalities, blindness and difficulties with temperature regulation.

Neuronal migration. Neurons begin to form in an area of the brain called the ventricular zone, peaking during the second to fourth months of gestation and finishing by 24–25 weeks’ gestation, which is close to the age of viability for preterm infants. After formation, the neurons migrate out to initiate formation of a cortical plate that differentiates and organizes to form the layers of the cerebral cortex. Programmed cell death or apoptosis of some of the newly formed neurons occurs in human fetuses; generally this occurs to the greatest extent in the earliest developing areas of the cortex (Rakic & Zecevic, 2000). Surviving cells will form six overlapping and interconnected layers of cells that characterize the cerebral cortex. Each layer has distinct patterns of afferent (incoming) and efferent (outgoing) connections to other parts of the brain. Occasionally, the process of neuronal formation and migration does not proceed normally and this results in brains (and skulls) that are smaller or larger than usual. Affected infants often have severe seizure disorders and mental retardation. The formation and migration of neurons are processes that are sensitive to environmental conditions, which will be discussed in later sections.

Synaptic elaboration. Initially, the differentiation of neurons and production of synapses are under genetic control and proceed similarly in all fetuses and infants in order to set up the basic neural networks that are important for neurobehavioral function. During development, each neuron elaborates dendrites and an axon. The axon is used as a superhighway by the transmitting neuron to rapidly send a signal that causes the release of neurotransmitters across a synapse to the dendrites of receiving neurons. These relays across specific neurons in different parts of the brain make up neuronal networks for specific brain functions such as auditory perception, memory, and voluntary motor function. The building of these neuronal networks begins in the fetus as neurons differentiate axons and dendrites and subsequently begin to form synapses with other neurons.

In nonhuman primates such as rhesus monkeys, all regions of the cerebral cortex appear to undergo synaptogenesis in a burst that occurs during a relatively short time interval. Two investigators in the 1990s suspected that this would not be true in human beings because specific brain functions come “on line” at different points of development. For example, even very young infants can hear and respond to sounds (auditory cortex) whereas some types of memory, such as working memory (prefrontal cortex), develop much later. Huttenlocher and Dabholkar (1997) proposed that synaptogenesis would proceed at different rates in different parts of the brain. Their research showed that synaptogenesis proceeded more rapidly in the auditory cortex than in the prefrontal cortex during the fetal period, with prefrontal synaptogenesis continuing on until about 3.5 years when the density of synapses was similar in these two areas. As these young synapses are used, they are strengthened. Those that are not used will die back (Haydon & Drapeau, 1995). The pruning of synapses occurs postnatally after the early infantile burst of synaptogenesis and is thought to be highly influenced by environmental inputs. How the fetal environment may affect the formation of synapses will be discussed later in this chapter.

Myelination. The last process of brain development involves the production and laying down of myelin. Myelin is a fatty substance that is produced from glial cells. In the cerebral cortex, glial cells develop in the germinal matrix during the latter half of gestation and migrate out, align themselves along axons, and begin to form myelin. Myelination of axons results in an increased speed of transmission that allows for faster transmission of neural impulses. Relatively little myelination occurs in the fetus, and this occurs predominantly in the peripheral nervous system, spinal cord and brainstem (Paus et al., 2001). In the spinal cord and brainstem, myelination of the sensory areas precedes that of the motor systems. Myelination continues on for decades after birth.

Influences on Brain Development

Chromosomal abnormalities

The chromosomes can be thought of as the blueprint for brain development, and therefore chromosomal abnormalities can interfere with brain development at all stages. The most commonly recognized chromosomal abnormality, trisomy of chromosome 21, results in Down syndrome. Fetal studies of Down syndrome have shown normal brain development through 22 weeks’ gestation, but by the time of birth, 20–50% fewer neurons are noted, and those have abnormal distributions, particularly in cortical layers V and VI (Wisniewski, 1990). Additionally, the prenatal development of synapses within the cortical layers proceeds abnormally, with decreases in protein markers of synaptogenesis noted during fetal life (Weitzdoerfer, Dierssen, Fountoulakis, & Lubec, 2001). However, most of the neuropathologic abnormalities seen in the brains of people with Down syndrome arise after birth as synaptogenesis and myelination proceed. There have been few studies of neurobehavioral function of newborn infants with Down syndrome, but low muscle tone is consistently noted after birth. Other neurobehavioral impairments in infants with Down syndrome may be relatively subtle in the first year of life, progressing over time and correlating with the more subtle abnormalities of fetal brain development in these infants. For detailed discussion of the postnatal development of infants with Down syndrome see chapter 12 in this volume.

Nutrition and brain development

The fetal brain grows more rapidly than other body organs; in a newborn infant, 12% of the body mass is due to the weight of the brain, compared to 2.8% of an adult’s body mass (Bogin, 1999). Furthermore, the newborn brain accounts for 87% of the total resting metabolic rate (Leonard, Snodgrass, & Robertson, 2007) which is higher than requirements seen in older children and adults and higher than seen in other species. This means that the process of normal fetal brain development and the synthesis and release of fetal neurotransmitters requires the ongoing provision of relatively high amounts of all nutrients. However, protein, energy, specific types of fats, iron, zinc, copper, iodine, selenium, vitamin A, choline, and folate are particularly important for fetal brain development and subsequent neurobehavioral function. The importance of nutrition during gestation was illustrated by experience with a severe famine in Holland in 1944–5. Women who did not receive sufficient rations of food during midgestation and the third trimester had infants with smaller head circumferences (reflecting poor brain growth) than infants born to Dutch women before or after the famine (Roseboom et al., 2 001). It should be noted that although malnutrition of pregnant women is not particularly common in developed countries, deficiencies of specific nutrients do occur as a result of maternal medical conditions such as diabetes, or medications such as oral contraceptives.

Early in fetal life, nutrient deficiencies may result in severe impairments. For example, folate is a vitamin that may become depleted with the use of birth control pills. Folate deficiency during the first few months of pregnancy can result in neural tube defects such as spina bifida (Rayburn, Stanley, & Garrett, 1996). Later in gestation, deficiencies of nutrients that are utilized globally, such as protein and energy, will result in a general lack of neuronal proliferation, differentiation and synapse formation (Georgieff, 2007). Poor transplacental transfer of both oxygen and nutrients occurs in infants with intrauterine growth restriction. Severely affected infants are at risk for low intelligence, behavioral problems, and poor memory abilities (Geva, Eshel, Leitner, Fattal-Valevski, & Harel, 2006; Walker & Marlow, 2008). These problems may lead to school difficulties and lowered economic potential in adulthood (Low et al., 1992; Strauss, 2000).

In contrast, some nutrients are utilized predominantly in specific neural pathways to synthesize neurotransmitters or in pathways that are particularly metabolically active at certain times in development. These deficiencies may have more specific effects. For example, iron is important in the function in parts of the neural pathways for recognition memory. Fetal iron deficiency may occur in the fetus, particularly in infants of diabetic mothers who are in poor control of their diabetes (Petry et al., 1992). These infants have been shown to have memory deficits starting at birth and persisting over the first year of life (DeBoer, Wewerka, Bauer, Georgieff, & Nelson, 2005; Sidappa et al., 2004). Although there are few specific studies of iron deficient fetuses, in animal models, iron deficiency disturbs a number of developmental processes, including the synthesis of monamine neurotransmitters and myelination. Information on the consequences of postnatal nutritional deficiencies is found in chapter 2 in this volume.

Effect of drugs, medications, and toxins on brain development

A wide variety of drugs, medications, and toxins have been shown to affect the fetus (Trask & Kosofsky, 2000). Fetal effects can occur via several mechanisms. First, drugs, medications, and toxins that can cross the placenta may result in acute intoxication of the fetus at the time of the ingestion. If the ingestion is near the time of birth, the newborn may show transient signs of drug intoxication. Second, regular use of physically addictive drugs during pregnancy can result in drug withdrawal in the newborn infant. Finally, specific exposures early in pregnancy or chronically throughout gestation may result in disturbances in brain developmental processes and subsequent cognitive and behavioral sequelae. The effects of such exposures may be variable, depending on the timing, dose, duration, and genetic vulnerability. In addition to the biologic effects of drug and alcohol exposure on the fetus, women who drink or use drugs during pregnancy may suffer from poverty, chronic stress, poor nutrition, and mental health problems. Women who use drugs and alcohol also have high rates of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder that may be...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series

- Title

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Introduction

- PART I: Bioecological Risks

- PART II: Psychosocial Risks

- PART III: Developmental Disorders

- PART IV: Intervention and Policy Issues