- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

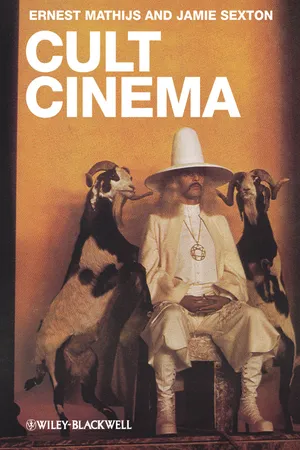

Cult Cinema: an Introduction presents the first in-depth academic examination of all aspects of the field of cult cinema, including audiences, genres, and theoretical perspectives.

- Represents the first exhaustive introduction to cult cinema

- Offers a scholarly treatment of a hotly contested topic at the center of current academic debate

- Covers audience reactions, aesthetics, genres, theories of cult cinema, as well as historical insights into the topic

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Cult Cinema by Ernest Mathijs,Jamie Sexton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medios de comunicación y artes escénicas & Historia y crítica cinematográficas. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I

Receptions and Debates

Chapter 1

Cult Reception Contexts

We have proposed in our introduction that cult cinema is primordially known through its reception. In this chapter we provide a conceptual view of various elements that inform cult reception contexts. In order to illustrate how cult receptions differ from mainstream or normalized trajectories our attention first goes to the paradigmatic historical exemplar of cult cinema, namely the midnight movie. Next, we will outline the significance of a phenomenological approach to cult film reception. Subsequently, we will theorize the kind of experience cult receptions offer, and the value it generates.

Midnight Movies

Traditionally, the midnight movie is associated with New York. J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum (1991: 310) observed that, on a worldwide scale, “New York is Palookaville when it comes to midnight movies,” and there were vibrant late night scenes across North America and Europe.1 Yet the New York scene is the only one thoroughly investigated and therefore we will use it as our key example.

Most scholars agree New York's midnight movie scene started when, in the late 1960s, underground and avant-garde theaters, with established clienteles and institutional affiliations, started programming risqué and exploitative materials. Mark Betz (2003) argues this shift was encouraged when “kinky” foreign art films and American underground films came together, near the end of the 1960s, in an exploitation/art circuit that emphasized the countercultural potential of cinema. Parker Tyler (1969) suggests a cross-fertilization between filmmakers who started to include more sex and violence in their films, and the demands of theaters catering to more permissive taste patterns, created a momentum in which practitioners and patrons encouraged each other to go ever further (Tyler 1969). The film usually credited with initiating the transition is the infamous Flaming Creatures, with its Dionysian theme and brutal rape-orgy. It was seized at several screenings and stunned audiences at others (for more on this film, see Chapters 3 and 14). Soon, other films with provocative aesthetic attitudes, and shocking or politically radical imagery drew similar receptions: Queen of Sheba Meets the Atom Man, Blow Job, Sins of the Fleshapoids, and Chafed Elbows, which Tyler describes as “the offbeat of the offbeat.” It had a “marathon run at a small East Village theatre” (Tyler 1969: 53). Probably the most cultist trajectory was that of Kenneth Anger's Scorpio Rising and Invocation of My Demon Brother, both of which ran for long periods of time at late night slots in theaters East of Greenwich Village (Betz 2003; Tyler 1969). A constant reference in the receptions of these films was that of physical and mental liberation from repression – a function similar to that of ancient rituals.

At the beginning of the 1970s a string of New York theaters started midnight programming. The underground repertory was complemented with exploitation films with kaleidoscopic and apocalyptic motives, revivals of previously banned films, new and explicit horror, films pushing the boundaries of sexual permissiveness, and exotic and surreal foreign films (Figure 1.1). The acceleration was a sign of the vibrancy of the counterculture, and of its widening into radical “outsider” films – the weirder the better. Topping them all was the visceral and symbolically heavy Mexican western-on-acid El Topo. Virtually unadvertised, El Topo sold out the Elgin theater for half a year. After a while, its screenings were described as a “midnight mass” (Hoberman and Rosenbaum 1991: 94). With the success of El Topo, the midnight movie really took off. Films as diverse as George Romero's zombie film and civil rights-metaphor Night of the Living Dead, Alejandro Jodorowsky's The Holy Mountain (a mystical adaptation of René Daumal's Mount Analogue to which Jodorowsky improvised a clever ending), and the mind-boggling surrealism of Viva la muerte attracted repeat audiences looking for “underground” thrills, and gusts of revelations – often aided by illegal substances. With these films, the midnight movie added an anti-establishment stance to its radical aesthetics; increasingly graphic depictions of sex and violence and explorations of immorality correlated with the audience's anxieties about the “violence engulfing the United States” (Hoberman and Rosenbaum 1991: 99, 112). Even if this feeling that the midnight movie exemplified a revolutionary attitude was more an impression than a fact, for midnight movie viewers the era's general unrest seemed to synchronize with what they experienced on screen – as if it predicted “the end of the world as we know it.”

Figure 1.1 Midnight movie classics from 1970 to 2002: from left to right, El Topo, The Rocky Horror Picture Show, and Donnie Darko.

As the 1970s progressed, the countercultural movement lost momentum. Midnight movies became ever more outrageous, but as their popularity widened across campuses, generic and aesthetic radicalism replaced ideological commentary. Art house and B-movie distributors such as Janus films and New Line Cinema became engaged in the midnight movie. Lesbian vampire movies, porn chic, blaxploitation movies, and foreign philosophical allegories such as Antonio das Mortes, The Saragosa Manuscript, or WR: Mysteries of an Organism, replaced the original batch of films. The most notorious among these films was Pink Flamingos, which tested viewers' threshold for revulsion – exactly the reason for its successful reception.

By the late 1970s, the midnight movie had become a staple of alternative cinema exhibition, the urban and college town equivalent of the drive-in. It was characterized by a hedonistic and wildly extravert context of rambunctious yet joyous celebrations. Many of the films championed in the circuit were as flamboyant as their audiences, with as figureheads campy rock musicals such as Tommy, or The Rocky Horror Picture Show. Proudly self-referential, these films were as much performances of cults, as cults themselves. Because of its endless runs Rocky Horror became a repertory in its own right (Weinstock 2007; Austin 1981a). Occasionally, “original” cults would still develop, around enigmatic films such as Eraserhead.

In the 1980s, much of the midnight movie attitude moved to VCR viewing, where “pause” and “rewind” functions on the remote control replaced the theatrical repeat viewing experience. What survived were nihilistic or flamboyant post punk movies such as Heavy Metal, the hardcore Café Flesh, or Liquid Sky. By the end of the decade many of the original midnight theaters had closed their doors, and filmmakers joined the burgeoning “independent” scene, or went underground again, with Abel Ferrara (King of New York) and Larry Fessenden (Habit) as crossover exceptions (Hawkins 2003). Only with large intervals would new midnight movie cults appear. The most prominent ones – Priscilla, Queen of the Desert and Donnie Darko – became the phenomenon's de facto eulogies. In 2001 “everything changed”, writes Joan Hawkins:

The World Trade Center in New York City was destroyed . . . The geography of downtown Manhattan has changed. So has the mood in the USA. And it's not at all clear what new avant-gardes and cult films might rise up to address what seems at this point to be a new era (one in which irony, for example, may not be considered an appropriate response to anything) (2003: 232).

For Hawkins, the cult of the midnight movie, a “moment when we believed that direct intervention in the country's spectacle would do some good,” was over (2003: 232).

As befits cult receptions, the midnight movie did not really die. Since the 1990s the demise of the original phenomenon was balanced by three other trends. First, new films found their ways into festivals, which increasingly included midnight showings as part of their programs. Second, midnight premieres also became a feature of blockbuster releases vying for cult status. Third, the midnight movie phenomenon went into meta-mode. Donnie Darko, for instance, arguably the most famous midnight movie after 9/11, is also a meta-midnight movie. Its audiences at the New York Pioneer Theater, aware of the legacy of the midnight movie phenomenon, were not only continuing a tradition that had existed for more than thirty years, they also consciously knew they were contributing to the heritage of the phenomenon by keeping it alive, or honoring the tradition by paying lip service to it. A decade after its first midnight run, college campuses, art houses, and festivals still screen Donnie Darko at midnight for this reason. Other instances of the meta-mode of the midnight movie include nostalgic revivals and queer celebrations of often overtly mainstream “classics” such as John Hughes's teen comedies (Ferris Bueller's Day Off), or sword and sorcery fantasy films (Conan the Barbarian). Their midnight success relies on the kitsch and camp attitude Rocky Horror had cemented as a core characteristic of the cult reception trajectory, and it reclaims some of the irony Hawkins claims it lost by exposing topical political attitudes through cheesy old movies. In its most recent form, this reflexive nostalgia has also included the original midnight movies, with relaunches of El Topo joining the never-ending runs of Rocky Horror and occasional newcomers, such as The Room (Bissell 2010).

In sum, the midnight movie highlights the key characteristics of a cult reception trajectory: films lumped together in a lively and “countercultural” exhibition context by their capacity to commit, through outrageously weird and explicit imagery, subcultural audience collectives, and to elicit performances of fandom and obsessions with the interconnectedness of elusive details intrinsic as well as alien to the films that enables allegorical and political interpretations that position themselves outside the realm of normalcy.

The Difficulty of Researching Cult Cinema

As the exemplar of the midnight movie illustrates, cult reception contexts are extremely heterogeneous. According to Mathijs and Mendik (2008a: 4–10), part of why they are called cult is because these receptions contain multitudes of competing and opposite discourses that stand in contrast of what a “normal” consumption process ought to be like. How does one begin to research such diverse contexts? At the basis of the cult reception context lies a fundamental philosophical question: does the value of a cultural product lie in its features and intentions or in the eye of the beholder? This question has important implications for the methodology of researching cult cinema.

Mathijs and Mendik (2008b: 15–16) distinguish between two schools of thought on this problem, with different implications:

ontological approaches to cult cinema are usually essentialist: they try to determine what makes “cult cinema” a certain type of movie . . . Phenomenological approaches shift the attention from the text to its appearance in the cultural contexts in which it is produced and received. Such attempts usually see cult cinema as a mode of reception, a way of seeing films (2008b: 15).

In the ontological approach, the reception process is one that affirms the properties of the product. In the phenomenological approach the reception process negotiates these properties in the light of how they make themselves known – as a kind of phenomenon. Mathijs and Mendik refer to the work of Jerome Stolnitz as an effort that tries to solve the deadlock between these two positions. For Stolnitz (1960a, 1960b) any value is less a matter of the properties of the work or the viewer than of the experience generated by the flow of meaning during the process of perception. Stolnitz distinguishes between objectivist, subjectivist, and objective relativist views of experience. Objectivism, like the ontological approach, places the essence of value in the work itself – as if the work carries meaning within itself. This makes perception a process of detection. Subjectivism, on the contrary, identifies value as a faculty of the perceiver – as if the audience places its own meanings upon the work. This makes the work “empty.”

Most reception studies of cinema embrace this approach. Janet Staiger (1992), for instance, explains that in order to understand how films work, and how the strategies through which they are given value operate, one has to distinguish between meanings generated through texts, through readers, and through contexts. Throughout, however, one has to accept

that cultural artifacts are not containers with immanent meanings, that variations among interpretations have historical bases for their differences, and that differences and change are not idiosyncratic but due to social, political, and economic conditions, as well as to constructed identities such as gender, sexual preference, race, ethnicity, class, and nationality. (Staiger 1992: xi)

Staiger argues that the best methodology for stressing contextual factors is to shift the focus of subjectivism from the mind of the spectator to the material conditions (the labor) involved in assigning meaning to a work – she calls this methodology a neo-Marxist approach. According to such an approach, studies of receptions should place emphasis on the use-value, exchange-value, and symbolic value of films (the latter being the value that is not expressed in material terms but in terms of the knowledge, expertise, kudos, and status, but also the dangers for exclusion and isolation any affiliation brings).

There have been several attempts to carve out procedures for this methodology. One attempt, by Barbara Klinger (1997), distinguishes between diachronic and synchronic approaches to film reception. The first stresses the materials that feature in a chain of events over time during a film's reception; the second emphasizes the materials from events that co-occur within the reception. The first method gives breadth, the second depth. Because cult reception trajectories are known to be volatile it is necessary to use both approaches simultaneously. Moreover, cult reception contexts are highly influenced by what Martin Barker (2004) has called unpredictable “ancillary materials”: already existing artifacts and discourses that relate to the upcoming release that lead to polemics and legends and that prevent a nice match between expectations and the actual experience. The best example is probably the myth surrounding the troubled production history of Casablanca. Another good example is the abrupt way in which Night of the Living Dead was introduced to audiences, as part of a matinee double bill, before it became a midnight movie. This means that an essential part of the cult reception context is that it is “fractured.” Its smooth running is interrupted or otherwise compromised, and audiences struggle to find an appropriate frame of reference for the newly released film.

Another attempt concentrates on the units of meaning that circulate in receptions. Each reception contains “intrinsic” and “extrinsic” references. Following David Bordwell (1989: 13), intrinsic references can be labeled “cues,” elements of the film and its immediate production context used by viewers as tools in their construction of arguments about the film. Extrinsic references are “quotes,” influences from outside the regular context that interfere with the reception. The degree to which a film's public course takes on the characteristics of a cult reception often depends on the abundance and the weight of extrinsic references. The longer a film's public visibility lasts (even in small communities), and the bigger the influences, the more likely it is to fracture a smooth reception. Controversies and moral panics are frequently a major part of the fractures in a cult reception trajectory.

There are some complications with the attempts we sketched. Topical events can penetrate so far into a film's reception they take over its direction. This is what initially happened to Donnie Darko. Even though it had been set for the Halloween weekend, traditionally a time for darker, more adult fare, Donnie Darko was too meta-generic to pose as a horror film, and the destruction of New York's World Trade Center on September 11th had temporarily eliminated audiences' appetites for dark materials and provocations. As one critic put it in hindsight: “why seek out talking rabbits warning of the end of the world when it already seemed to be happening?” Cult receptions also demonstrate psychological tendencies towards “insulation.” Russ Hunter (2009, 2010) observes how subsequent to Suspiria (usually considered his best film) the reception of Dario Argento's films petrified into a series of mantras, which led to a refusal to include new achievements (or rather the lack of them) into reappraisals. The more Argento's reception became mantra-like, the more frequently it was called “cult.” Such inoculation from new debates demonstrates how difficult it is to distinguish between instances of cultism that are convictions, and instances that are performed as attitudes, and if indeed there is a measurable difference.

Finally, there is the complication of a cult reception context's endurance. Films such as The Wizard of Oz or Casablanca have been enjoyed as cult by generations of audiences. The label cult is also instrumental to the long-term reputation of The Rocky Horror Picture Show, or Pink Flamingos, films...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Dedication

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Receptions and Debates

- Part II: Themes and Genres

- Filmography

- References

- Credits and Sources

- index