![]()

CHAPTER 1

The Housing Bubble

Owners of U.S. commercial real estate, comprising principally office buildings, multifamily rental properties, retail properties, and the hotel and hospitality sector, draw upon both consumers and businesses as their customers. The businesses that occupy our office buildings and book our hotels, and our retailers, in turn, depend largely upon consumers, whose spending accounts for over 70 percent1 of our gross domestic product. One way or the other, U.S. commercial real estate is dependent upon the U.S. consumer.

Consumer spending was decimated by the bursting of the housing bubble, which began unfolding in 2006, while American businesses, particularly small businesses, were ravaged by the abrupt and unprecedented curtailment of credit following on its heels. The credit freeze itself was triggered by the subprime mortgage crisis.

The sudden seizure of our credit markets in August 2008 was preceded by the sale of Merrill Lynch to Bank of America,2 was followed by the Lehman bankruptcy and then–Treasury Secretary Paulson seizing government-sponsored enterprises Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac and placing them under federal conservatorship.3

To understand where our commercial real estate markets are headed, we must gauge the health and future prospects of the U.S. consumer. This, in turn, requires an understanding of the subprime mortgage crisis, the building and bursting of the U.S. housing bubble, and where the housing sector is headed. Consumer purchasing power and sentiment are driven in large measure by the relative health of the housing and equities markets.

The systemic risk to our banking sector created by trillions of dollars worth of defaulted securitized subprime (and later prime) residential mortgages spread like a wind-fueled brushfire throughout our worldwide banking system, and as well to the myriad other investors attracted to diverse pools of U.S. home mortgages. Real estate private equity firms, life insurance companies, public and corporate pension funds, and hedge funds, to name a few—really, a cadre of investors, which had become, by virtue of the securitization process, a shadow mortgage banking system unto itself—were drawn to home mortgages, then thought to be a bullet-proof asset class.

THE U.S. AFFORDABLE HOME OWNERSHIP MANDATE

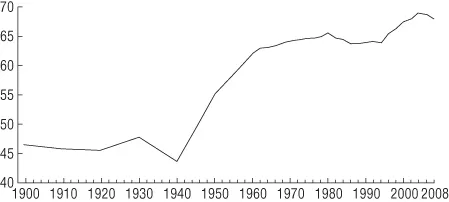

To understand the subprime mortgage crisis, we must roll back the clock. For the first four decades of the twentieth century—prior to the onset of World War II—the percentage of home ownership in the United States hovered in a tight range—43.6 percent to 47.8 percent, a spread of only 4.2 percent.4 Discounting the 1940 figure as an aberrational low brought about by the Great Depression, the range tightens further—45.6 percent to 47.8 percent—a spread of a mere 2.2 percent over a span of four decades. (See Figure 1.1.)

After the end of World War II, however, a dramatic change took place. The percentage of home ownership jumped to 55 percent in 1950 and then began a steady climb from there up to 66.2 percent at the turn of the millennium. By 2004–2005, the U.S. home ownership rate had skyrocketed to over 69 percent.

The stunning post–World War II increase in U.S. home ownership rates—going from about 47 percent to 69 percent (representing a 47 percent increase in the home ownership rate)—was not brought about by laissez-faire market forces, but rather by aggressive government intervention designed and driven by a liberal vanguard so blinded by the political correctness of marching toward the American Dream for America’s minorities that they could not foresee the devastating consequences to both the supposed beneficiaries of their intervention, as well as to all other Americans (and really, people the world over). Regrettably, however, good intentions are not enough; as Oscar Wilde said, “all bad poetry springs from genuine feeling.” And as the late neoconservative publisher Irving Kristol added, “the same can be said for bad politics.”

Empowered by the influence of Congress over the government-sponsored enterprises and that of the banking sector over Congress and Fannie and Freddie; assisted by mortgage originators who, courtesy of Wall Street’s securitization prowess, retained no stake in the loans they originated and therefore had no reason to underwrite them soundly, and by the appraisers they controlled; aided and abetted by an oligopoly of credit raters who, protected by our government from the pressures of free-market competition, had fallen asleep at the switch; and enabled by the swollen supply of cheap and easy money put into place in the years preceding the bursting of the housing bubble by the Greenspan Fed, there was no stopping the mainstream-media–praised racial lending quotas established under our affordable home ownership mandate. The results, given the scale of the U.S. housing market, were nothing less than cataclysmic.

THE BIRTH OF THE GOVERNMENT-SPONSORED ENTERPRISES

Initially the government intervention was relatively tame and not racially driven. Starting with the G.I. Bill,5 which provided home loans to returning soldiers, and the Federal National Mortgage Association or “Fannie Mae” as it is now commonly called, the federal government undertook a consistent policy of promoting home ownership, primarily through subsidizing home mortgage loans and making them easily and readily available, and secondarily via tax policy by making home mortgage interest deductible.6

Fannie Mae was chartered in 1938 by Franklin Delano Roosevelt as a governmental agency in the wake of the Great Depression. In 1968, it was converted by Lyndon Johnson to a private stockholder-owned (but government-sponsored) enterprise or GSE,7 in order to remove its activity from the balance sheet of the federal budget.

Fannie Mae was formed as part of the New Deal to promote liquidity in the mortgage market by providing a robust and efficient secondary mortgage market—a market where home mortgage loan originators could come to sell their mortgage paper and replenish their capital in order to redeploy it and originate more loans.

Even though conceived during the severe financial stresses of the Great Depression, Fannie Mae purchased conforming mortgage loans with sensible down payment requirements. Initially, Fannie’s down payment requirement was 20 percent.8 Fast forwarding to the present, the down payment requirement imposed by the Federal Housing Administration, an arm of the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, which issues explicit government-backed mortgage insurance,9 was reduced to an astonishing 3.5 percent,10 nearly one-seventh of the original mandate.

Although there have been very low (including 0 percent) down payment programs, beginning with the Veteran’s Administration as early as 1944, these programs were used far more broadly after 2000. The big change came with the greater use of second-lien home purchase loans (sometimes called piggyback loans) beginning in 2002, which let more borrowers put no money down to buy a house.11

THE U.S. AFFORDABLE HOME OWNERSHIP MANDATE IS RADICALIZED AND RACIALIZED

A radicalization of the federal policy of promoting home ownership took place during the 15-year period preceding the bursting of the housing bubble—1992 to 2007—initially led by the efforts of the Clinton Administration, most notably then–Attorney General Janet Reno, and thereafter by leading liberal congressmen and senators, whose campaign coffers were stuffed with contributions from Fannie Mae and its sister agency, Freddie Mac They included Senate Banking Committee Chairman Christopher Dodd and House Financial Services Committee Chairman Barney Frank. Some Republicans as well fell prey to the irresistible lure of housing subsidies, including President George W. Bush, who signed into law the American Dream Downpayment Act in 2003.

Besides the Clinton Administration, Senator Dodd, Congressman Frank, and their liberal minions, another key player in the liberal left vanguard pushing for ever higher home ownership rates among American minorities was the since disgraced liberal advocacy group, ACORN (Association of Community Organizations for Reform Now).12

In 1992, under intense lobbying pressure from ACORN, Congress passed the Federal Housing Enterprises Financial Safety and Soundness Act, also known as the GSE Act.13 Forced to comply with the GSE Act’s “affordable housing” mandate—a mandate pushed through by ACORN—Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac now own or are responsible for (via securitization) a jaw-dropping $5.5 trillion of residential mortgages, roughly half of all U.S. residential mortgages (by dollar value, but more than half in number of mortgages).

THE COMMUNITY REINVESTMENT ACT

Congress had bought into ACORN’s goal of pressuring the GSEs—Fannie and Freddie—into purchasing home mortgage loans with a heavy emphasis on mortgages made to low-income minority borrowers looking to purchase homes with razor-thin down payments. These “affordable housing” loans were in turn made by the banks under an earlier law—the Community Reinvestment Act of 1977, an act of Congress signed into law by President Carter, designed to stop the alleged bank practice known as “redlining” (the supposed discriminatory credit practices against minority, low-income, inner city neighborhoods).

The CRA’s mandate merely admonished “each appropriate Federal financial supervisory agency to use its authority when examining financial institutions to encourage such institutions to help meet the credit needs of the local communities in which they are chartered consistent with the safe and sound operation of such institutions.” It was easy for aggressive liberal lawmakers to twist loan disapproval rate statistics to the end of converting the CRA’s seemingly benign mandate into a radicalized and racialized monster.

As Mark Twain quipped over a century and a half ago, “facts are stubborn, but statistics are more pliable.” Distorting loan denial rate statistics was easy, and the liberal mainstream media did whatever it could to help move the process along.

As Hoover Institution (Stanford University) economist and author Thomas Sowell compellingly explains in his book, The Housing Boom and Bust, instead of reporting that the vast majority of mortgage applications submitted by both blacks and whites were approved, as was the case, the mainstream media only reported the differences in rejection rates. Whenever possible, rationale differences in loan applicants’ qualifications were ignored.

The trivial differences in approval rates among the races were explained by sound underwriting standards. If a certain percentage of African Americans or Hispanics of a given income level were denied mortgages while a higher percentage of whites in that same income bracket were granted their applications, other relevant factors like the amount of cash being put down or the overall cash assets of the applicant were ignored.

And, as Mr. Sowell aptly hypothesized, if 99 percent of loan applications by whites were granted while 98 percent of blacks’ applications were granted, though it would be technically true in such a case to say that blacks suffered twice the rejection rate as whites, such an observation hardly presents a clear picture of what was really happening—that the great majority of all loan applications by both whites and blacks were approved.

Although actual approval rates were not quite that high, Mr. Sowell’s point—that rejection rate statistics were being used to distort the true picture—is irrefutable. In any event, as Mr. Sowell noted, Asians had a higher mortgage approval rate than did whites, a statistic conveniently ignored by both the mainstream media and our lawmakers.

The whole notion that banks intentionally refused to make loans to African Americans or Hispanics simply because of the color of their skin and not because of some reasonably grounded fear that applicants of any race with inadequate assets, income, or credit histories would not be able to pay back the loans they sought, in and of itself should have raised the hair on the backs of our necks.

Why would the very same executives whom President Obama now describes as “fat cat bankers” refuse to turn a profit from the interest paid by putative borrowers simply because of the color of their skin? When exactly did the “fat cat bankers” lose their capitalist urges? Was their racism so strong that mortgage bankers were prepared to pay for it in millions of dollars of lost profits (which would then go to their nonracist competitors), even after spending millions of advertising dollars in order to attract borrowers?

Astute commercial trial lawyers look for simple economic motivations to explain human behavior. Isn’t a far more plausible and simpler theory that these bankers had sound, objective reasons for denying the few loans they did in fact deny, or for granting such applications and charging higher interest rates to make up for the higher default rates to applicants (of any race) with poor credit characteristics?

This irrational insistence on seeing racism in what was nothing more than sound underwriting criteria consistently applied is explained by what another Hoover Institute scholar, Shelby Steele, referred to in a December 30, 2009 Wall Street Journal article as an American sophistication—“the sophistication of seeing what isn’t there rather than what is”—likening the process to the parable of the emperor’s new clothes.

As related by Mr. Steele, “[t]he emperor was told by his swindling tailors that people who could not see his new clothes were stupid and incompetent. So when his new clothes arrived and he could not see them, he put them on anyway so that no one would think him stupid and incompetent. And when he appeared before his people in these new clothes, they too—not wanting to appear stupid and incompetent—exclaimed [at] the beauty of his wardrobe. It was finally a mere child who said: ‘The emperor has no clot...