- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

By revealing the contextual conditions which promote or hinder democratic development, Comparative Politics shows how democracy may not be the best institutional arrangement given a country's unique set of historical, economic, social, cultural and international circumstances.

- Addresses the contextual conditions which promote or hinder democratic development

- Reveals that democracy may not be the best institutional arrangement given a country's unique set of historical, economic, social, cultural and international circumstances

- Applies theories and principles relating to the promotion of the development of democracy to the contemporary case studies

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Comparative Politics by John T. Ishiyama in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Politics & International Relations & Comparative Politics. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Edition

1Subtopic

Comparative Politics1

Introduction: Comparative Politics and Democracy

This book is not an introduction to political science in general, but an introduction to one of the major subfields of the discipline – comparative politics. It is designed as a book that builds upon a student’s knowledge of politics, and assumes that the student has some basic familiarity with some central questions in political science – questions such as: What is politics? What is the state? What is government? What is a political system? Although designed primarily as a book for students with some familiarity with politics and political science, this book can be used by both “beginners” in the field and by more advanced students. It can be used by more advanced students because rather than being about “countries,” it is about theories and principles in comparative politics. By adopting a problem-based learning approach, this can help even those students with little innate interest in comparative politics to understand how these concepts and principles can be used to make sense of hotspots like Iraq or Afghanistan.

This book is organized around a basic pedagogical principle: that students learn best when theories and concepts are understood in application to solving a problem (or problem-based learning). Hence this book is organized around a problem. How does one promote the development of political democracy? What are the factors that help explain the emergence of political democracy? Although some may object to the seemingly prescriptive nature of the question (the implication that democracy should exist everywhere), I adopt this focus for two reasons. First, it is a very practical question. Knowing the factors that affect the development of democracy can help students understand why “building” democracy in post-war Iraq or Afghanistan is so difficult, if not impossible. Thus, the question is not prescriptive – rather it presumes that students need to ask this question first to realize that democracy may not be the best institutional arrangement, given a set of historical, economic, social, cultural and international circumstances. Second, it provides an issue on which “to hang our theoretical hats” – it demonstrates that some very practical questions can be addressed using theories that students read about in texts – it makes the field relevant and real.

Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method

However, before we begin to address the question about how to build a democracy, we do need to address some preliminaries – when we talk about a text book on “comparative politics,” what do we mean? How does comparative politics fit as a subfield of political science? What has characterized the evolution of comparative politics as a subfield over time and how has that evolution reflected the development of political science generally? Finally, to sum up this chapter, I offer a brief outline of how this book is organized, and why is it organized the way it is.

Turning to a definition of comparative politics, it is first important to note that comparative politics is a subfield of political science, which includes other subfields, such as International Relations, Political Thought/Theory, Public Administration, Judicial Politics, etc. In American political science, American Politics is also considered a subfield, but this view is not shared by European scholars, for instance, who simply include American politics as a case within comparative politics. In this book I share that European perspective, and consider the United States as one of the cases among many we investigate for comparative purposes.

There have been many different definitions of comparative politics offered by a variety of political science scholars. These can be divided into at least three general types: First, there are those who think of comparative politics large as the study of “other” or “foreign” countries – in most cases, this means countries other than the United States (Zahariadis, 1997, p. 2). A second approach emphasizes comparative politics as a subject of study. For instance, David Robertson (2003) defines comparative politics as simply the study of “comparative government” whose essence is to compare the ways in which different societies cope with various problems, the role of the political structures involved being of particular interest. Most definitions of comparative politics, however, think of the field as both a method of study and a subject of study (Lim, 2006). Thus, for example, Howard Wiarda notes that the defining feature of comparative politics is that it “involves the systematic study of the world’s political systems. It seeks to explain differences between as well as similarities among countries. In contrast to journalistic reporting on a single country, comparative politics is particularly interested in exploring patterns, processes, and regularities among political systems” (Wiarda, 2000, p. 7). These topics can include:

[The] search for similarities and differences between and among political phenomena, including political institutions (such as legislatures, political parties, or political interest groups), political behavior (such as voting, demonstrating, or reading political pamphlets), or political ideas (such as liberalism, conservatism, or Marxism).

(Mahler, 2000, p. 3)

Comparative politics is thus both a subject and method of study. As a method of study, comparative politics essentially is based on learning through comparison (which is, after all, the heart of all learning). There are different ways to compare, but for now it is sufficient to say that comparative politics as a method is a way of explaining difference. As Mahler (2000, p. 3) notes, “Everything that politics studies, comparative politics studies; the latter just undertakes the study with an explicit comparative methodology in mind.” As a subject of study, comparative politics focuses on understanding and explaining political phenomena that take place within a state, society, country, or political system. Defining comparative politics in this way as both a subject and method of study allows us to distinguish comparative politics, from, say, international relations which is concerned primarily (although not exclusively) with political phenomena between countries, as opposed to within countries. If we define comparative politics, at least in part, as a method of analysis, as opposed to simply the study of “foreign” or “other countries,” then it does not exclude the possibility of including the United States as a country to be studied, just as one might include Germany, or Russia, or Japan or Iraq.

So what is the comparative method? As we noted above, comparison is at the heart of all analysis. When one uses terms like bigger or smaller, greater or less, stronger or weaker to analyze anything, then by definition one is comparing. Indeed, for many scholars, being comparative is at the heart of political science. For instance, for Harold Lasswell (1968, p. 3), comparative politics was identical to political science because “for anyone with a scientific approach to political phenomena the idea of an independent comparative method seems redundant,” because the scientific approach is “unavoidably comparative.” Similarly Gabriel Almond (1966, pp. 877–878) equated the comparative and scientific method when he argued that “it makes no sense to speak of a comparative politics in political science since if it is a science, it goes without saying that it is comparative in its approach.”

Nonetheless, as others have argued, in political science the comparative method is much more than just comparison. For the notable comparative politics scholar Arend Lijphart (1971), the comparative method is a unique approach especially designed to address a methodological problem in political science. It is a set of strategies that one uses to deal with situation of having too few cases, and too many potential explanatory factors. For instance, suppose one were to try to explain why political revolutions occur? Certainly one could examine a single case, such as the Russian Revolution of 1917. What are the potential causes that precipitated that revolutionary upheaval – perhaps it was due to the strain of World War I on Russia’s relatively underdeveloped economy? Perhaps it was due to the social and economic developments prior to World War I that had created working-class chaffing under the yolk of autocracy? Or perhaps it was because of the organizational capabilities of the leaders of the Bolshevik Party (particularly Vladimir Lenin)? Or maybe it had more to do with the undue influence of the monk Grigorii Rasputin over the Empress Alexandra, which paralyzed the Emperor Nicholas’ ability to act decisively? How would one be able to ascertain which of the potential theoretical causes (military defeat, social and economic transformation, organizational capacity of the opposition, and the political psychology of the incumbent leadership) had the most explanatory power when one has only a single case – the answer is, of course, one cannot. This is the essence of the problem of having too many explanatory variables and too few cases.

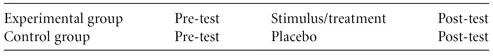

There are ways, of course, established in the natural and social sciences, to deal with this problem. In the life sciences, a common technique is the experimental method. This method, involves the use of an experimental group and a control group. The experimental group receives the treatment, or exposure to a stimulus. In many ways the stimulus can be seen as the “causal factor” we wish to test. On the other hand, the control group is exposed to the stimulus or treatment. The composition of the experimental and control groups should be identical, or as close to identical as possible. So if one were using human subjects, then one would want an identical number of men and women in each group, an identical number of representatives of different racial and ethnic group, or socioeconomic groups, etc. In addition the members of the control group receive a “placebo” (usually an inert substance which makes it less likely that the participants in the experiment realize that they are not receiving the active treatment). Thus the use of identical experimental and control groups (and a placebo) is meant to control for alternative factors that might explain difference on the post-test scores (such as gender differences or differences due to the subjects realizing they are not receiving the active treatment). By controlling for these alternative explanatory factors, one can presumably assess the true effects of the stimulus, treatment, or primary causal factor (see Table 1.1).

Table 1.1 Classical experimental design.

However, especially in the social sciences, the subjects of study are not easily amenable to experimental control, especially in the study of countries (as is the case in comparative politics). What many scholars advocate is a quasi-experimental approach (see Mannheim, Rich, and Wilnat, 2002) in which the logical structure of the classical experiment is pursued, but via non-experimental means. In other words, we still seek to control for the effects of alternative factors, thus isolating the effects of the variable in which one is most interested. One quasi-experimental technique is the statistical method (Lijphart, 1971). In the statistical method, we control for the effects of other variables via techniques such as linear regression (and its variants) which simultaneously estimate the effects of a number of independent variables (causes) while controlling for the effects of others. The statistical method, however, in order to work requires a generally large number of cases relative to the number of independent variables (causes) that are included in the analysis. This is a challenge for scholars studying comparative politics, when our universe of cases is limited by the number of countries, and the existence of an almost infinite number of explanatory variables. For example, if one were to try to identify all of the possible causes of political democracy, one can imagine an extremely large number of causes, probably more than the number of countries in the world. To avoid this potential problem, one technique is to “truncate” the model, or purposely reduce the number of explanatory variables to be tested to only those “theoretically” relevant (that is, those that are mentioned in the literature). This of course is what is most often done in quantitative comparative political analysis, but the downside of this is that there are always potentially important variables that are left out of the analysis.

Another technique that is employed is the “comparative method” which Arend Lijphart (1971, p. 685) identified as a unique quasi experimental strategy used to deal with the situation of having too many potentially causal variables and too few cases. The comparative method is related to the statistical method in that it seeks to establish controls without having experimental control over the subjects of study. Thus, like the statistical method, the comparative method is “an imperfect substitute” for the experimental method (ibid., p. 685). However, unlike the statistical method, the comparative method does not exert statistical control over variables. Rather control is attained through other means. The comparative method is specifically designed for a very small number of cases (ibid., p. 684).

There are of course a number of different types of comparative designs, but the most common is the Similar Systems Design (sometimes knows as Mill’s Method of Difference, named after John Stuart Mill), which consists of comparing very similar cases which only differ in the dependent variable. This allows one to “control” for a number of factors in order to assess which differences account for variation in the dependent variable. For example, in my own work (Ishiyama, 1993), I have examined the impact of the electoral system on party systems development during the political transition period just prior to the collapse of the Soviet Union, comparing the then republican elections in Estonia and Latvia. These two countries were selected because they were very similar in a number of key respects. First, both had been annexed by the Soviet Union in the same year (1940) and both were characterized by ethnic bipolarity (where there were two main groups in each republic, the indigenous Latvian and Estonian populations, and the Russophones); both had similar levels of economic development, and both were regarded as “advanced” republics in the USSR. In the initial competitive elections introduced in 1989, the political systems were roughly parliamentary, and both systems were unitary. The one key dimension in which they varied was the electoral system they adopted to govern the first competitive elections. In Latvia, a single-member district plurality system was employed (as was the case in the rest of the “elections” in the USSR, at least technically). In Estonia, however, the authorities there experimented with a variation of a proportional representation system called the Single Transferable Vote (STV) used in countries like Ireland and Malta. Thus, by controlling for other theoretically important variables that might explain party systems development (by selecting similar countries) one can ascertain the effect of the one variable in which they differ – in this case, the electoral system.

On the other hand, there is the Most Different Systems Design/Mill’s Method of Similarity: it consists in comparing very different cases, all of which, however, have in common the same dependent variable. The goal is to find the common circumstance (or common denominator) which is present in all the cases that can be regarded as the cause (or independent variable) that explains the similarity in outcome.

The Evolution of Comparative Politics

The Ancients and Comparative Politics

Where did comparative politics come from? How has the field evolved over time? To some extent the study of comparative politics is as old as the study of politics itself. The earliest systematic comparisons of political systems were carried out by the Ancient Greeks. For instance, Plutarch tells a story, in his Lives of the Noble Grecians and Romans, of the scholar Lycurgus of Sparta who traveled widely around Greece and the Eastern Mediterranean recording the strength and weaknesses of the political regimes among the various city-states he encountered. However, the two most noteworthy scholars in Ancient Greece, at least in terms of their impact on comparative politics, were Plato and Aristotle. The Republic by Plato and Politics by Aristotle are widely viewed as the first great works of political science, covering such key issues as the nature of power, characteristics of leadership, different forms of government, and the relationship between state and society and economics and politics.

Although both Aristotle and Plato had much in common (particularly in terms of their desire to understand the design of the ideal political system), the approaches to understanding and knowledge (or epistemologies) were quite different. On the one hand, Plato was much more concerned with what should be and with normative issues such as justice and right than Aristotle (although Aristotle was motivated by these concerns as well). However, where the two really differed was in their understanding of how humans come to know things. For Plato, to understand involved insight. Indeed, Plato thought of understanding as much more than just observation or reality. Thus, for instance, his “Parable of the Cave” is a metaphor for ignorance and knowledge.

The parable goes something like this: Imagine a cave in which prisoners are chained to a wall so all they see are the shadows thrown on a wall in front of them by the light shining behind them from the mouth of the cave. All they have known and see are these shadows which they mistakenly perceive as reality. Yet if one were freed, and saw the daylight behind, that person would see things as they really are, and realize how limited one’s vision was in the cave (Plato, 1945, p. 516). Merely observing perceived reality is thus not real. Discovering what should be is what is real for Plato. From Plato is derived the normative tradition in political science.

On the other hand, Aristotle (1958) really represents a more “empi...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Principles of Political Science Series

- Title page

- Copyright page

- 1 Introduction: Comparative Politics and Democracy

- 2 Democracy and Democratization in Historical Perspective

- 3 Economics and Political Development

- 4 Political Culture and Ethnopolitics

- 5 Social Structure and Politics

- 6 Democratization and the Global Environment

- 7 Electoral Systems

- 8 Legislatures and Executives

- 9 Comparative Judicial Politics and the Territorial Arrangement of the Political System

- 10 Conclusion: Principles in Application

- Index