![]()

1

Introduction

John Valasek

Texas A&M University, USA

A flying machine is impossible, in spite of the testimony of the birds

—John Le Conte, well-known naturalist, ”The Problem of the Flying Machine,” Popular Science Monthly, November 1888, p. 69.

1.1 Introduction

Current interest in morphing vehicles has been fueled by advances in smart technologies such as materials, sensors, actuators, their associated support hardware and microelectronics. These advances have led to a series of breakthroughs in a wide variety of disciplines that, when fully realized for aircraft applications, have the potential to produce large improvements in aircraft safety, affordability, and environmental compatibility. The road to these advances and applications is paved with the efforts of pioneers going back several centuries. This chapter seeks to succinctly map out this road by highlighting the contributions of these pioneers and showing the historical connections between bio-inspiration and aeronautical engineering. A second objective is to demonstrate that the field of morphing has now come nearly full circle over the past 100 plus years. Birds inspired the pioneer aviators, who sought solutions to aerodynamic and control problems of flight. But a smooth and continuous shape-changing capability like that of birds was beyond the technologies of the day, so the concept of variable geometry using conventional hinges and pivots evolved and was used for many years. With new results in bio-inspiration and recent advances in aerodynamics, controls, structures, and materials, researchers are finally converging upon the set of tools and technologies needed to realize the original dream of aircraft which are capable of smooth and continuous shape-changing. The focus and scope of this chapter are intentionally limited to concepts and aircraft that are accessible through the unclassified, open literature.

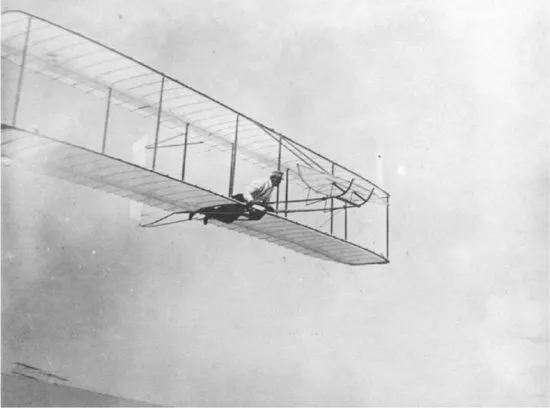

1.2 The Early Years: Bio-Inspiration

Otto Lilienthal was a nineteenth-century Prussian aviator who had a lifelong fascination with bird flight which led him into a professional career as a designer. He appeared on the aviation scene in 1891 by designing, building, and flying a series of gliders. Between 1891 and 1896 he completed nearly 2,000 flights in 16 different types of gliders, an example of which is shown in Figure 1.1. The wings of these gliders were described as resembling “the outstretched pinions of a soaring bird.” The bird species which captivated him most were storks, and the extent to which birds influenced Lilienthal is evidenced by two of the many books which he wrote on aviation: Our Teachers in Soaring Flight in 1897, and Birdflight as the Basis for Aviation: A Contribution toward a System of Aviation in 1889 (Lilienthal 1889). His observations on bird twist and camber distributions were influential in the development of his air-pressure tables and airfoil data. Interestingly, Lilienthal also made attempts at powered flight but chose to only study wings with orntithopteric wingtips. His insistence on the use of flapping wing tips in preference to a conventional propeller is an indication of the extent to which he was captivated by bird flight (Crouch 1989). Several early pioneers recognized the value in morphing as a control effect. Edson Fessenden Gallaudet, Professor of Physics at Yale, applied the concept of wing warping to a kite in 1898. While not entirely successful, this kite nonetheless embodied the basic structural concepts which would appear in aircraft designs much later (Crouch 1989). Independently, Orville and Wilbur Wright, correctly deduced that wing warping could provide lateral control. Wilbur remarked to Octave Chanute in 1900 that “My observation of the flight of buzzards leads me to believe that they regain their lateral balance, when partly overturned by a gust of wind, by a torsion of the tips of the wings. If the rear edge of the right wing tip is twisted upward and the left downward, the bird becomes an animated windmill and instantly begins to turn, a line from its head to its tail being the axis” (Wright 1900). This observation led to the design of the 1902 Wright Glider, which incorporated wing warping for lateral (roll) control (Figure 1.2). The warping was accomplished by wires attached to the pilot's belt, which were controlled by his shifting body position. Although this craft was flown by the Wrights as both a kite and a glider, it was during flights of the latter type that the need for a directional (yaw) control was first realized, and then solved with the creation of the rudder. Correctly recognizing that achieving harmony of control would greatly improve the control and usefulness of an aircraft, in October 1902 the Wrights developed an interconnection between warping of the wing and warping of the vertical tail. Thus the concept of what would later become the aileron-to-rudder interconnect or ARI was born. With the problems of longitudinal control, lateral control, directional control, and control harmony solved, the 1902 Wright Glider became essentially the world's first successful airplane (Crouch 1989). These developments paved the way for the success of the powered 1903 Wright Flyer a year later.

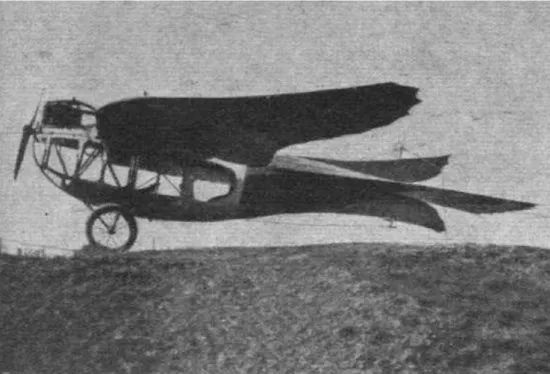

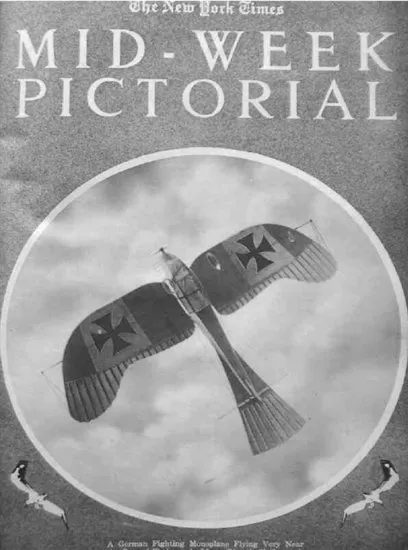

The Etrich Taube (“dove” in German) series of designs have probably been the ultimate expression of bio-inspiration to aircraft design. In fact, except for the omission of flapping wings, the Taube designs are essentially bio-mimetic, i.e. directly mimicking a biological system (Figure 1.3). The Etrich Luft-Limousine / VII was somewhat unique for an airplane of its time since it employed multi-material construction. This consisted of an aluminum sheet covering from the nose to just behind the wings, with wood used everywhere else. The fuselage structure used wooden rings and channel-section longitudinal members and the windows were celluloid and wire gauze. The initial Taube designs were created by Igo Etrich in Austria in 1909. The original inspiration for the unique wing planform on Taube designs was not a bird wing, but the Zanonia macrocarpa seed, which falls from trees in a slow spin induced by a single wing. This was not successful, yet the influence of birds on later adaptations of this wing design can clearly be seen (Figure 1.4). Like the Wright designs, the Taube designs employed wing and horizontal tail warping via wires and external posts, although the vertical tail surfaces were hinged. Despite contemporary aircraft designs which featured vertical tails of a size and proportion that would be recognizable in modern designs, the Taube designs mimicked birds so much that the dorsal and ventral fins comprising the vertical tail surfaces were very small. Ultimately, the very small vertical tail surfaces became a distinguishing characteristic of the Taube designs.

The Wright and Taube designs demonstrated that warping controls can be effective on aircraft with thin and flexible wings. But the invention of the now conventional hinged controls, such as ailerons and rudders, was essential for later aircraft with more rigid structures and metallic materials. Thus the problem of materials and structures has been a central consideration to morphing aircraft from the outset. By the onset of the First World War in 1914 and in the years afterward, virtually all high performance aircraft used conventional hinged control surfaces instead of warping. With the advent of aircraft with relatively rigid metallic structures in the 1930s, the path to morphing clearly lay in changing the geometry of the aircraft via complex arrangements of conventional hinges, pivots, and rails rather than warping.

1.3 The Middle Years: Variable Geometry

During the inter-war years in France, Ivan Makhonine conceived the idea of a telescoping wing aircraft. The aim was to improve cruise performance by reducing the induced drag, or the drag due to the creation of lift. This was to be accomplished by reducing span loading which is the ratio of aircraft weight to wing span. As shown in Figure 1.5, the mechanism works like a stiletto knife, except that the wing can also be retracted automatically since it was pneumatically powered with a standby manual system. The fixed landing gear MAK-10 was first flown in 1931, followed by the retractable landing gear MAK-101 in 1933. The MAK-101 was flown many times over the next several years until it was destroyed in its hangar during a USAAF bombing raid late in the Second World War. Makhonine continued his research into the telescoping wing concept post-war, culminating in the last aircraft in the series, the MAK-123 which first flew in 1947. The MAK-123 was a four-seat passenger aircraft that flew well and was reported to have adequate handling qualities, but was damaged in a forced landing and never flew again.

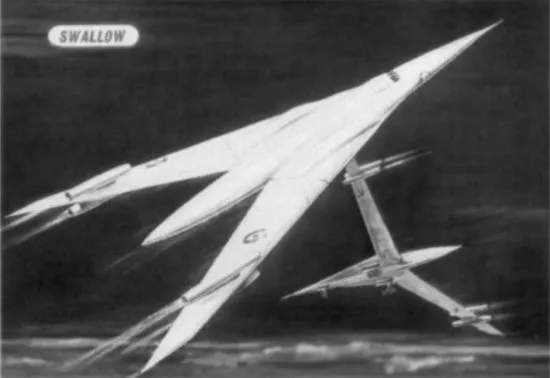

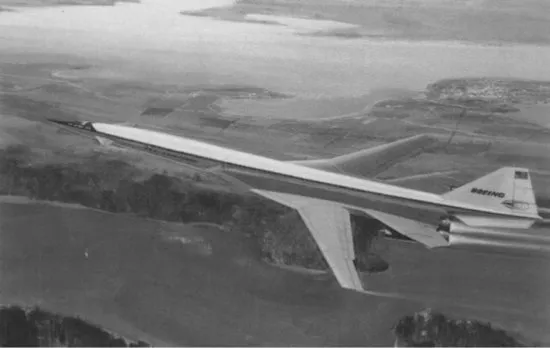

British aircraft designer Sir Barnes Neville Wallis, well known as the inventor of the geodesic structural design concept used in the Vickers Wellington medium bomber, also investigated novel variable geometry configurations. Although he did not invent the swing-wing concept, Wallis devoted much effort to making what he called the “wing-controlled aerodyne” practical as a means of achieving supersonic flight. His two main goals were to use variable geometry as a solution to handling the center of gravity changes duri...