![]()

Part D

Case Studies

![]()

Chapter 16

Discovery of Sunitinib as a Multitarget Treatment of Cancer

Catherine Delbaldo, Camelia Colichi, Marie-Paule Sablin, Chantal Dreyer, Bertrand Billemont, Sandrine Faivre and Eric Raymond

16.1 A Brief Introduction to Tumor Angiogenesis

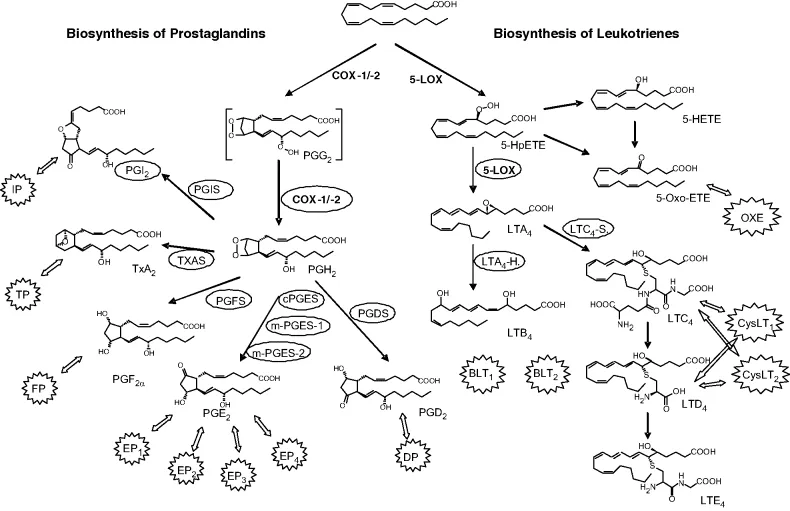

Since Folkman's works in the 1970s, we have learned that angiogenesis plays a crucial role in tumor growth and metastatic spread [1]. It is acknowledged that the growth of primary tumors and metastasis beyond a few millimeters is frequently associated with hypoxia and/or necrosis occurring primarily in central tumor areas. In this scenario, hypoxic conditions are known to trigger the angiogenic switch associated with the overexpression of several survival genes, including hypoxic inducible factor 1α (HIF1α) in cancer cells. HIF1α, as a potent transcription factor, facilitates the expression of several genes involved in tumor angiogenesis such as vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) (Figure 16.1). In other tumors such as renal cell carcinoma, Von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) mutations were shown to stabilize HIF1α and prevent its degradation, resulting in a VEGF expression that closely mimics that induced by hypoxia. The gradient of VEGF expression in the extracellular matrix surrounding cancer cells may eventually attract circulating endothelial cells, facilitate their proliferation, and differentiate to form tubules that can progressively self-organize in novel microvessels. VEGF-dependent microvessels are unstable, continuously reorganizing, self-renewing, and leaky, and require the presence of platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF)-dependent pericytes to stabilize. In the absence of pericytes, microvessels may spontaneously collapse to form additional area of necrosis and hypoxia that, in turn, stimulate further angiogenesis. Furthermore, while tumor vessels are developing, cancer cells may also acquire mesenchymal properties such as migration, invasion, and motility, using newly generated microvessels as channels for metastatic spreading. Tyrosine kinase receptors, including platelet-derived growth factor receptors (PDGFRs), fibroblast growth factor receptors (FGFR), and vascular endothelial growth factor receptors (VEGFRs) and their ligands, have also been shown to play important roles in tumor growth and angiogenesis. Inhibition of VEGF signaling through the use of antibodies or VEGFR antagonist has demonstrated potent antitumor effects either as single agents or in combination with other drugs, suggesting that inhibition of angiogenic pathways might be used to circumvent resistance to classical anticancer agents [2–7]. More recently, the humanized anti-VEGF monoclonal bevacizumab antibody, in combination with chemotherapy, was associated with an increased survival in patients with advanced colon cancer [8]. Interesting activity of bevacizumab has also been showed in metastatic breast carcinoma and metastatic non small-cell lung carcinoma (NSCLC), associated with chemotherapy [9, 10].

16.2 Discovery of Sunitinib from Drug Design to First Evidence of Clinical Activity

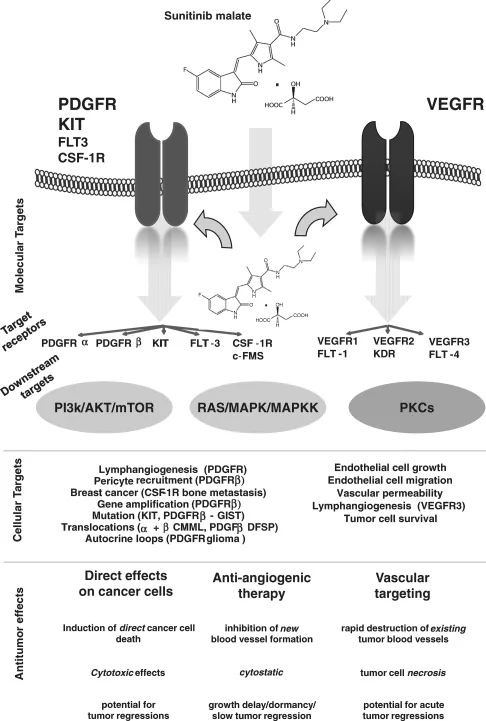

Sunitinib is a small-molecule drug designed by Schlessinger and Ullrich. Sunitinib works by blocking multiple molecular targets (Figure 16.2) implicated in growth, proliferation, neoangiogenesis, and metastatic spreading [11]. Sunitinib was one of the last small-molecule drugs developed by Sugen, a small biotech company named after its founders and located in California. Sunitinib was the only drug that continued clinical development despite its consecutive acquisitions by Pharmacia and Pfizer. Two important targets of sunitinib, VEGFR and PDGFR, were shown expressed by several solid tumors and are thought to play a crucial role in the genesis and maintenance of tumor neovascularization [12]. Single-agent sunitinib was early recognized as a potent anticancer treatment in tumors depending on to VEGF and VEGFR for angiogenesis. Sunitinib lacking selectivity was first considered as a “dirty drug” before evidence became available suggesting that the lack of selectivity may be considered as an advantage and stands as a novel paradigm for multitargeted agents. In preclinical models, sunitinib showed activity against tumor cells as well as many noncancer cells such as endothelial cells, pericytes, and fibroblasts, commonly recognized as stroma cells supporting the growth and maintenance of tumors. First evidence of activity of sunitinib in human was identified in phase I first-in-man trials. The aim of phase I trials is usually to focus primarily on drug safety; however, it offers an opportunity to identify specific activity, leading to the development of novel anticancer agents. This may also make it possible to treat patients with advanced tumors. As a result, while tumor response in phase I trials remains a secondary endpoint, case reports of objective responses are now regarded as crucial signals of activity, stimulating and guiding further phase II/III studies, finding novel niche indications. Sunitinib was one such anticancer agent. During the course of the phase I trial with sunitinib, a strong antitumor activity was witnessed as reflected by the unusually high number of objective responses in several tumor types (neuroendocrine tumors, gastrointestinal stromal tumors, and renal clear-cell carcinomas) [13]. In this chapter we will review the mechanisms of action of sunitinib and its placement into the current armamentarium used for the treatment of malignancies based on current and ongoing clinical trials.

16.3 Pharmacology of Sunitinib

Sunitinib (sunitinib malate; SU11248; SUTENT; Pfizer Inc, New York, NY), is an indol derivative (C22H27FN4O2) that displays stability and solubility. Sunitinib stands as a novel oral multitargeted tyrosine kinase inhibitor with antitumor and antiangiogenic activities. Sunitinib has been identified as a potent inhibitor of VEGFR1, VEGFR2, VEGFR3, KIT [stem cell factor (SCF) receptor], PDGFRα, and PDGFRβ in both biochemical and cellular assays [14, 15] (Figure 16.2). In vitro, sunitinib inhibited growth of cell lines driven by VEGF, SCF, and PDGF and induced apoptosis of human umbilical vein endothelial cells [15]. Sunitinib exhibited dose- and time-dependent antitumor activity in mice, potently repressing the growth of a broad variety of human tumor xenografts [15–19]. In vivo, sunitinib caused bone marrow depletion and effects in the pancreas in rats and monkeys, as well as adrenal toxicity in rat (microhemorrhages). In monkeys, a slight increase in arterial blood pressure and QT interval were reported at higher doses. In vitro metabolism studies demonstrated that sunitinib was metabolized primarily by cytochrome CYP3A4, resulting in formation of a major, pharmacologically active N-desethyl metabolite, SU012662. This metabolite was shown to be equipotent to the parent compound in biochemical tyrosine kinase and cellular proliferation assays, acting toward VEGFR, PDGFR, and KIT [20]. SU012662 was the major plasma metabolite in mice, rats, and monkeys in vivo. SU012487 (an N-oxide metabolite) was the major metabolite in dog but was infrequently observed in humans. Radiolabeled orally administrated sunitinib in preclinical species was excreted primarily in the feces (rat > 71%; monkey > 84%). Pharmacokinetic/pharmacodynamic data from animal studies showed that target plasma concentrations of sunitinib plus SU012662 capable of inhibiting PDGFRβ and VEGFR2 phosphorylation were established in the range of 50–100 ng/mL [14–17]. Interestingly, those data were consistent with those observed in patients with acute myeloid leukemia in whom exposure to sunitinib led to a sustained inhibition of FLT3 phosphorylation in blast cells [21]. Although initial studies were planned to provide continuous administration, the 4-weeks-on/2-weeks-off schedule was selected at the request of the health authorities to allow patients to recover from potential bone marrow and adrenal toxicity observed in animal models.

16.4 Safety of Sunitinib

A phase I study showed that the maximum tolerated dose (MTD) of sunitinib was 75 mg and the recommended dose was a 50-mg/day, 4-weeks-on/2-weeks-off schedule [13]. Hypertension and asthenia appear to be the most common adverse effects with sunitinib and have been observed with several other inhibitors of VEGF and VEGFRs [3, 4, 7, 13]. Hypertension usually requires standard antihypertensive therapy, and treatment discontinuation is rarely necessary. A decrease in left ventricular ejection fraction is a rare but potentially life-threatening complication. A phase I study with sunitinib on a 2-weeks-on/1-week-off regimen in 12 patients with solid tumors, showed that 5 patients presented asymptomatic grade 2 decreases in the left ventricular ejection fraction [22]. Other adverse events are skin toxicity, consisting of dry skin, edema, and hand–foot syndromes with/without bullous lesions, observed only at doses ≥ 75 mg/day that may require treatment discontinuation for a few days and/or dose reduction [13]. The most consistent pathological changes are dermal vascular modifications with slight endothelial changes in grade 1/2 hand–foot syndromes and more pronounced vascular alterations with scattered keratinocyte necrosis and intraepidermal cleavage in grade 3 hand–foot syndromes and peribullous lesions (Figure 16.3) [13]. Sunitinib induces endothelial cell apoptosis in vitro and in animal tumor models, and pathologic changes observed in the skin toxicity suggest that dermal vessel alteration and apoptosis might be due to direct anti-VEGFR and/or anti-PDGFR effects of sunitinib on dermal endothelial cells. Consistent with the effects of sunitinib on dermal endothelial cells, asymptomatic sublingual splinter hemorrhages were observed in several patients associated in one case with thrombocytopenia, suggesting microangiopathy [23, 24]. Thrombosis has been reported in several other trials of drugs that target VEGF and VEGFRs and was also observed with sunitinib [25, 26]...