![]()

Chapter 1

cAMP-Specific Phosphodiesterases: Modulation, Inhibition, and Activation

R. T. Cameron and George S. Baillie

Molecular Pharmacology Group, Institute of Neuroscience and Psychology, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Wolfson Building, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK

1.1 Introduction

Cell surface, 7-span, transmembrane receptors recognize various environmental stimuli and transform them into intracellular signals via associated G proteins. This allows cells, tissues, and organs to alter specific aspects of their homeostasis in response to physical or chemical challenges. As such, cellular signals propagated in this way must be highly regulated so that their amplitude and timing produce a measured, appropriate response. The signal must be strong enough to produce the desired effect but also be transient so that the cell can easily prepare for other potential challenges. Additionally, the signal must also be targeted to the correct functional machinery, which often resides in discrete intracellular locations; hence signaling must be compartmentalized. To achieve all of these goals, cells have developed signaling molecules known as second messengers to convey complex information from receptors, temporally and in three dimensions, into the cell to signaling nodes where functional decisions are made. Although it is known that second messengers can take the form of lipids, gasses, ions, or nucleotides, discoveries around one such messenger, cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP), provided the conceptual framework on which the second messenger concept was based [1]. Soon after its discovery in 1958 [2], it was realised that cAMP was synthesized at the membrane by adenylate cyclase in response to hormones and degraded to 5′-AMP by the action of cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterases in the cytoplasm (reviewed in Ref. 1). One decade later, the discovery of the first cAMP effector molecule, Protein kinase A (PKA), was made and the cAMP signaling pathway was taking shape [3]. In the early 1980s, compartmentation of cyclic nucleotides was proposed by Brunton and colleagues when they noticed that stimulation of two different cardiac receptors (PGE receptor and the β-adrenergic receptor) both resulted in increases in cAMP and PKA activity, but only the β-agonist activated glycogen phosphorylase [4]. These different functional outcomes were underpinned by the activation of distinct PKA isoforms that were restricted to specific intracellular compartments [5].

Today, the notion of compartmentation within cell signaling pathways is widely accepted and there are many examples of signaling nodes where several key protein intermediates are anchored at discrete locations within cells. This is particularly true for the cAMP signaling pathway, where scaffolds, such as AKAPs, sequester PKA, phosphatases, phosphodiesterases, and PKA substrates to compartmentalize and orchestrate signals emitting from membrane-bound adenylate cyclase isoforms [6]. As cAMP positively transduces signals into the cell via PKA and the cAMP GEF EPAC [7], phosphatases and phosphodiesterases play the opposite role by dephosphorylating PKA substrates and hydrolizing cyclic nucleotides, respectively [8]. As hydrolysis by cAMP phosphodiesterases is the only route by which cAMP can be eliminated, these enzymes are poised to play a crucial role in intracellular signaling and as such represent excellent therapeutic targets [9].

Here we aim to review current knowledge on cAMP-specific phosphodiesterases and will describe their properties, distribution, and regulation and what is currently known about their inhibition by conventional-active-site directed compounds, novel allosteric inhibitor classes, and novel peptide disruptors. We will not discuss either cGMP-specific phosphodiesterases or dual cAMP-cGMP phosphodiesterses, as many more recent reviews have appraised current developments in those areas [10–16].

1.2 General Characteristics of Phosphodiesterases Specific For Cyclic Adenosine Monophosphate

1.2.1 Modular Structure of cAMP-Specific PDEs

Phosphodiesterases are divided into 11 families (reviewed in Ref. 17); PDE4, PDE7, and 8PDE are cAMP-specific, whereas PDE3, PDE6, and PDE9 are cGMP-specific, and the other 5 (PDEs PDE1, PDE2, PDE3, PDE10, and PDE11) have dual specificity with differing affinities for both types of cyclic nucleotide. The differing cyclic nucleotide specificity of specific PDE families is caused by a structural switch whereby a conserved glutamine residue within the catalytic unit is either free to rotate at will (dual specificity) or is locked into one of two positions by neighboring residues (one position = cAMP specificity; the other = cGMP specificity). As multiple genes with alternate splicing sites encode the various PDE families, the number of transcripts is large, and this results in the expression of a highly diverse collection of enzymes with divergent functional roles [18].

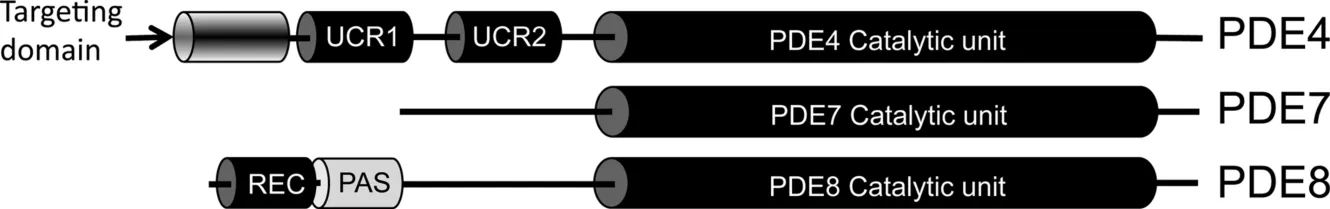

The modular structure of cAMP-specific PDEs (PDE4, PDE7, and PDE8) is represented in Figure 1.1.

PDE4 has the most complex framework consisting of a subfamily specific C-terminal domain and dual regulatory domains, upstream conserved region 1 (UCR1) and upstream conserved region 2 (UCR2), together with an isoform-specific N-terminal region [19]. PDE8 is characterized by its period, arnt, sim domain (PAS), and all three families have a conserved catalytic domain that acts to hydrolyze cAMP. Alignment of the amino acid sequence of PDE4, PDE7, and PDE8 shows that 11 of the 17 conserved residues seen in all PDEs are located within the catalytic pocket of these enzymes. The cAMP hydrolyzing machinery of all three PDE families have a similar structure containing 16 compact alpha helices neatly orientated into three subdomains [17]. Current knowledge of the potential of each cAMP-specific PDE family as therapeutic targets will be presented in separate sections.

1.2.2 PDE4s: Characterization and Regulation

Diversity of Isoforms

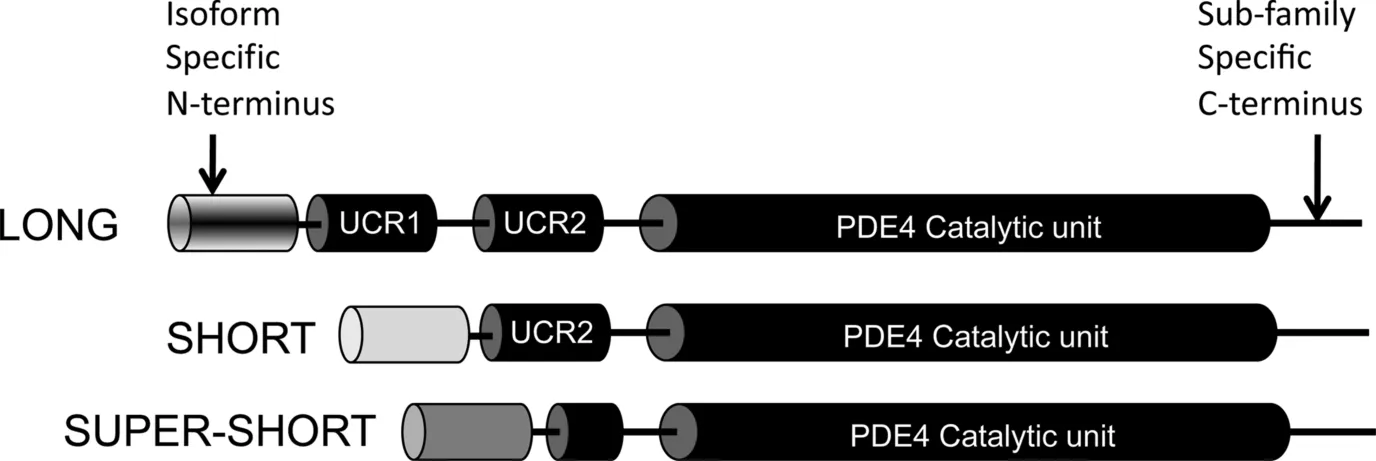

Pioneering studies on PDE4 family characterisation were done on the Drosophila dunce PDE locus that corresponds to the human PDE4D gene [20]. The fly PDE gene produced many transcripts, which corresponded to multiple distinct protein types, and this property is conserved in the mammalian PDE4D ortholog that results in the expression of 11 variants (PDE4D 1–11) [21, 22]. PDE4s are encoded by four genes (A,B,C,D), and these give rise to at least 25 different proteins (6 PDE4A forms, 5 PDE4B forms, 3 PDE4C forms, and 11 PDE4D forms) via mRNA splicing and promoter diversity [19]. The fact that all PDE4 enzymes have been highly conserved over evolution suggests that they play an important role in cAMP homeostasis, and it is now thought that each isoform has nonredundant functional roles in underpinning the compartmentalization of cAMP signaling [23]. As all PDE4 isoforms have similar Km and Vmax values for cAMP hydrolysis, their functional role is determined largely by their cellular location, interaction with other signaling proteins, and posttranslational modification. Discrete intracellular targeting of individual PDE4 isoforms is most often directed by a postcode sequence within their unique N-terminal domain (see Fig. 1.2) [24]. This region is responsible for promoting many of the protein--protein interactions and one protein--lipid interaction that act to anchor PDE4s to signaling nodes in subcellular compartments.

PDE4 enzymes can be broadly subdivided into four categories according to their sequence length and differential expression of regulatory modules (Fig. 1.2) [25]. Long isoforms contain UCR1 and UCR2, shortforms lack UCR1, supershortforms lack UCR1 and express a truncated UCR2, and dead shortforms lack UCR1 and UCR2 [26]. As stated previously, each isoform has a conserved catalytic unit and a unique N-terminal region. Additionally, all PDE4s have a C-terminal region that extends past the catalytic unit, and this is sub-family-specific [17]. The intricacy and complexity of each of the components described above is now becoming clear and will be discussed in the following review; however, it is obvious that the domain structure of PDE4s allow the cell to “dial up” bespoke PDE4s to fit immediate requirements for cAMP hydrolysis in a diverse range of cell types and tissues [27]. Such tailored expression allows precise targeting and regulation of PDE4s to control and shape local cAMP pools.

N-Terminal “Anchor”

The unique N-terminals of PDE4s are encoded by 5′ exons that are preceded by isoform-specific promoters. Many studies on the compartmentation of PDE4 enzymes have concluded that the N-terminal region directs their distribution by promoting the formation of complexes with scaffolds, regulators, or lipids. These include the scaffold proteins RACK1, AKAP18 [28], and β-arrestin [29–31], SRC family tyrosine kinases [32–34], immunophillin XAP2 [31], mAKAP [6], dynein complex member Nudel [35], and the β1-adrenergic receptor [36]. PDE4A1 is unique in that it is the only PDE4 discovered so far that is anchored to membranes by its N-terminal [37] and, as such, has provided the paradigm for elucidation of the N-terminal of PDE4s as tethers [38]. PDE4A1 is entirely membrane-bound locating to the Golgi apparatus and Golgi vesicles; however, if the unique 25mer N-terminal is removed, the PDE becomes cytosolic and more active [39]. Moreover, cytosolic proteins such as GFP or chloramphenicol acetyltransferase can be rendered membrane-associated by simply engineering the addition of the PDE4A1 25mer [40] and a 25mer peptide corresponding to the 4A1 N-terminal sequence inserts into lipid bilayers in <10 ms, as evidenced by stop-flow analysis [41]. Subsequent work showed that the membrane association of PDE4A1 was triggered by calcium [41]. These studies demonstrate that all the information required for intracellular targeting is encompassed within the N-terminal of PDE4A1 and this observation paved the way for the general consensus that the N-terminal region of PDE4s is essential for intracellular localization of PDE4s [38].

Further proof that confirmed the role of the unique regions of PDE4A subfamily members in conferring their cellular localisation was the observation that the N-terminal region of PDE4A4 and its rat homolog PDE4A5 contain a number of SH3 binding domains that direct binding to a number of members of the SRC-tyrosyl kinase family [33]. This association alters the conformation of PDE4s such that they exhibit an increase in sensitivity to rolipram in addition to directing the intracellular targeting of the enzyme. Additional experimentation also showed that one of the PDE4D enzymes, PDE4D4, also had the ability to associate with src, lyn, and fyn via its N terminal [34].

Another first for the PDE4 field was the realization that N-terminal targeting could result in the dynamic redis...