eBook - ePub

Testing Adhesive Joints

Best Practices

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Testing Adhesive Joints

Best Practices

About this book

Joining techniques such as welding, brazing, riveting and screwing are used by industry all over the world on a daily basis. A further

method of joining has also proven to be highly successful: adhesive bonding. Adhesive bonding technology has an extremely broad range

of applications. And it is difficult to imagine a product - in the home, in industry, in transportation, or anywhere else for that matter - that

does not use adhesives or sealants in some manner. The book focuses on the methodology used for fabricating and testing adhesive and bonded joint specimens. The text covers a wide range of test methods that are used in the field of adhesives, providing vital information for dealing with the range of adhesive properties that are of interest to the adhesive community. With contributions from many experts in the field, the entire breadth of industrial laboratory examples, utilizing different best practice techniques are discussed. The core concept of the book is to provide essential information vital for producing and characterizing adhesives and adhesively bonded joints.

method of joining has also proven to be highly successful: adhesive bonding. Adhesive bonding technology has an extremely broad range

of applications. And it is difficult to imagine a product - in the home, in industry, in transportation, or anywhere else for that matter - that

does not use adhesives or sealants in some manner. The book focuses on the methodology used for fabricating and testing adhesive and bonded joint specimens. The text covers a wide range of test methods that are used in the field of adhesives, providing vital information for dealing with the range of adhesive properties that are of interest to the adhesive community. With contributions from many experts in the field, the entire breadth of industrial laboratory examples, utilizing different best practice techniques are discussed. The core concept of the book is to provide essential information vital for producing and characterizing adhesives and adhesively bonded joints.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Edition

1Chapter 1

Manufacture of Quality Specimens

1.1 Preparing Bulk Specimens by Hydrostatic Pressure

1.1.1 Introduction

There are many test methods for the determination of failure strength data. Basically, they can be divided into two main categories: tests on neat resin or bulk specimens and tests in a joint or in situ. Tests in the bulk form are easy to perform and follow the standards for plastic materials. However, the thickness used should be as low as possible to represent the thin adhesive layer present in adhesive joints. Tests conducted on in situ joints more closely represent reality, but there are some difficulties associated with accurately measuring the very small adhesive displacements of thin adhesive layers. There has been intense debate about the most appropriate method and whether the two methods (bulk and in situ) can be related. Some argue that the properties in the bulk form may not be the same as those in a joint because the cure in the bulk form and the cure in a joint (thin film) may not be identical. In effect, the adherends remove the heat produced by the exothermic reaction associated with cure and prevent overheating. To minimize this problem, cure schedules should be selected to ensure that the thermal histories of the materials are similar in each case. Dynamic mechanical thermal analysis (DMTA) or differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) measurements can be made to compare the final state of cure of the materials (Section 6.1).

Bulk specimens are usually manufactured by pouring or injecting the adhesive in a mold with the final shape (Section 1.2), or by pressure between plates. The first method is suited to one-part adhesives that are relatively liquid. The mold can be open but can also be a closed cavity, in which case the adhesive needs to be injected. When the adhesive is viscous, in the form of a film or of two components, the second method generally gives better results. If the adhesive is viscous or in film form, the pouring (or injection) phase is difficult or impossible. On the other hand, the mixing of two-part adhesives can introduce voids. If the adhesive is liquid, the air bubbles can be removed by vacuum. da Silva and Adams [1] have used an “open” vacuum release technique to produce void-free specimens with limited success. If the adhesive is viscous, recent sophisticated machines in which the mixing is done at high speed under vacuum can ensure that the adhesive is void free. If the voids have been removed properly, the adhesive can be manufactured by pouring or injection, taking care not to introduce voids during this operation. A number of simple techniques have been used to reduce void incorporation during mixing and dispensing, such as mixing in a sealed bag by kneading and then snipping off a corner to dispense or preparing the adhesive in a syringe to minimize air entrainment. If not, the voids can be removed by high pressures and an excess of adhesive to compensate for the voids.

Although voids and other defects in bulk specimens may have minimal effects on averaged properties, such as modulus and other constitutive properties, they can have a significant effect on failure properties such as various strength metrics and strain at break. In reducing voids, it is important to understand where their source is. Voids can result from outgassing of the adhesive during cure, from air entrained in the adhesive during mixing or dispensing, and from absorbed water that evaporated at the elevated cure temperatures. Although some adhesives intentionally outgas to create foams, most adhesives do not outgas significantly. Especially when the cure temperature exceeds 100 °C, absorbed water in the adhesive can be vaporized, leaving the adhesive riddled with voids. Adhesive components that are known to absorb water may need to be dried before mixing to reduce voiding due to this latter mechanism.

1.1.2 Principle

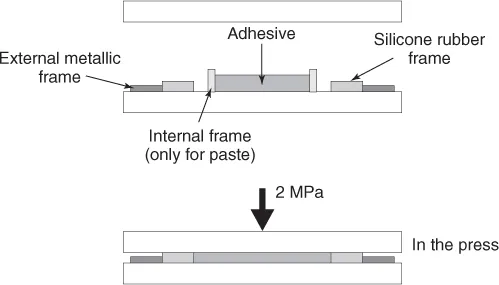

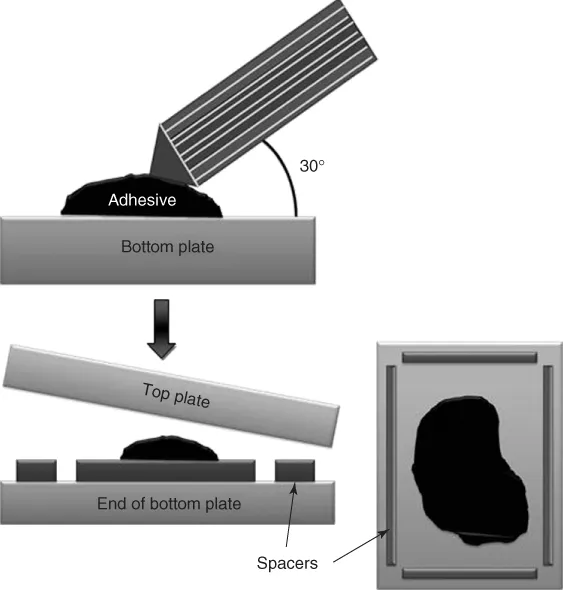

The technique described in the French standard NF T 76-142 works particularly well for producing plate specimens without porosity [1, 2]. It provides a technique for curing plates of adhesive in a mold with a silicon rubber frame under high pressure (2 MPa or 20 atm). The pressure is calculated using the external dimensions of the silicone rubber frame. The technique, shown schematically in Figure 1.1, consists of placing in the center part of the mold a quantity of adhesive slightly greater (5% in volume) than the volume corresponding to the internal part of the silicone rubber frame. There is a gap, at the beginning of the cure, between the adhesive and the silicone rubber frame. This gap enables, at the moment of application of the pressure, the adhesive to flow (until the mold is completely filled) and to avoid gas entrapment. Note that there is an external metallic frame to keep the silicone rubber frame in place. If the adhesive is a film, the lid is placed on top of the layers, but the load is applied only when the adhesive has the lowest viscosity to ease the adhesive flow. If the adhesive is a paste, the pressure is applied right from the beginning of the cure. However, an internal metallic frame is necessary to keep the adhesive at the center of the mold when being poured to guarantee that there is a gap between the adhesive and the silicone rubber frame. This frame is, of course, removed before the application of pressure. This technique is suitable for any type of adhesive, that is, liquid, paste, or film. Standard ISO 15166 describes a similar method (Figure 1.2) of producing bulk plate specimens. However, this standard does not include a silicone rubber frame and just uses spacers to control the adhesive thickness. The bulk specimens obtained have a poor surface finish and contain voids, especially for two-part adhesives.

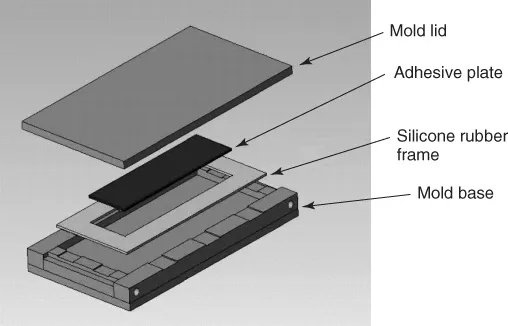

Figure 1.1 Adhesive plate manufacture according to NF T 76-142.

Figure 1.2 Adhesive plate manufacture according to ISO 15166.

1.1.3 Metallic Mold

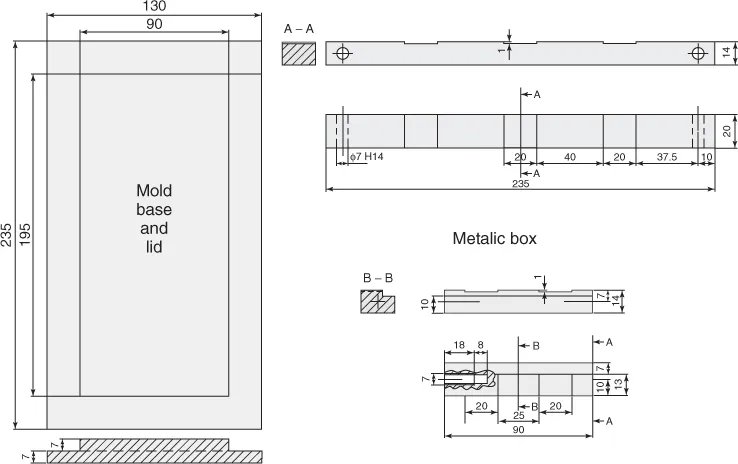

Standard NF T 76-142 recommends using a metallic frame with an area of 150 × 150 mm2 and a silicone frame with a width of 50 mm and a thickness of 2 mm to produce an adhesive plate of 100 × 100 × 2 mm3. A pressure of 2 MPa is applied on the external dimensions of the silicone frame, that is, in this case, 20 kN. The thickness of the silicone rubber frame gives the final thickness to the adhesive plate. However, a thin metallic frame may deform easily under pressure or due to an incorrect use, which must not occur if perfectly plane plates are to be obtained. Therefore, a more robust metallic support to keep the silicone frame in place is advised. For example, the mold represented in Figure 1.3 can be used. It consists of a base and a lid with a working area of 195 × 90 mm2 (external dimension of the silicone frame) for the application of the 2 MPa pressure (35.1 kN). That area is sufficient to machine two dogbone specimens for tensile testing. However, smaller or larger areas can be used. Four metallic pieces are put around the base and bolted to form a metallic box that fits the base and the lid. The metallic box keeps the silicone frame in place and also enables excess of adhesive to escape. Figure 1.4 shows an exploded view of the mold with the metallic frame, the silicone rubber frame, and the adhesive plate. All the pieces of the mold have a good finish (ground), especially the base and the lid, because they will dictate the surface finish of the adhesive plate. The metal used to build the metallic mold can be carbon steel (e.g., 0.45% C) in the annealed condition. It is cheap, easy to machine, and guarantees good heat dissipation.

Figure 1.3 Dimensions in mm of the metallic mold.

Figure 1.4 Exploded view of the mold to produce plate specimens under hydrostatic pressure.

1.1.4 Silicone Frame

The silicone rubber frame seals the adhesive very tightly enabling the application of hydrostatic pressure to the adhesive. The silicone rubber frame also serves as a thickness control since the thickness of the adhesive plate is equal to that of the silicone frame because of the incompressibility of the silicone. Generally, a thickness of 2 mm is used. Larger thicknesses can be used, but the exothermic reaction during cure can cause adhesive burning for some adhesives. Thicknesses of up to 16 mm have been produced with the mold presented in Figure 1.4. Thick plates can be used to produce round specimens. The silicone used is a room temperature vulcanizing (RTV) silicone. The hardness of the silicone is not critical, and soft (20 shore A) to hard silicones (70 shore A) can be used. In general, a silicone with 50 shore hardness is used. Sheets of silicone rubber can be purchased easily in drugstores. Alternatively, a sheet of silicone can be manufactured with uncured silicone using the metallic mold described above. The silicone can be cut to the final dimensions with a cutter. The width of the silicone rubber used for the mold presented above is 22.5 mm, which means that the internal space of the silicone rubber frame (also the dimensions of the adhesive plate) is 140 × 45 × 2 mm3. The width of the silicone rubber frame should not be less than 15 mm.

1.1.5 Adhesive Application

Before the adhesive application, the release agent must be applied to the metallic mold. It is not necessary to apply the release agent to the silicone rubber frame because most adhesives do not usually...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title Page

- Copyright

- About the Editors

- List of Contributors

- Chapter 1: Manufacture of Quality Specimens

- Chapter 2: Quasi-Static Constitutive and Strength Tests

- Chapter 3: Quasi-Static Fracture Tests

- Chapter 4: Higher Rate and Impact Tests

- Chapter 5: Durability

- Chapter 6: Other Test Methods

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Testing Adhesive Joints by Lucas F.M. da Silva, David A. Dillard, Bamber Blackman, Robert D. Adams, Lucas F.M. da Silva,David A. Dillard,Bamber Blackman,Robert D. Adams in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Chemical & Biochemical Engineering. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.