![]()

1

Steroids: a Brief History

The early history of steroids devolves almost exclusively about two compounds that had, at the time, been known for decades. These substances, cholesterol (1-1) and cholic acid (1-2) (Scheme 1.1) are available in large quantities from natural sources. This is arguably explains why these compounds were the first steroids to be obtained in pure crystalline form. Some gallstones, in fact, consist of as much as 90% of the neutral steroid cholesterol. This compound was isolated from those stones as pure crystals well before the birth of organic chemistry. The empirical formula for cholesterol, C27H46O, was established as early as 1888 (or alternatively C54H92O2, as the concept of a molecule was at the time still somewhat nebulous and not accepted by all chemists). This compound and many of its derivatives, referred as sterols [from the Greeks steros (solid)] are also available from plants. Ox bile from slaughterhouses proved to be a relatively abundant source of bile salts. The acids from acidification of the salts consist largely of cholic acid (1-2) and chenodeoxycholic acid (1-3). Each of these compounds was obtained as pure crystals at about the same time as cholesterol. The bile acids, it was subsequently found, are formed in the liver by oxidation of cholesterol. They serve as surfactants for absorption of fats from the intestine and also for excretion of cholesterol and other hydrophobic compounds. The relative abundance of pure cholesterol and bile acids focused early research aimed at unraveling the chemical structure of steroids on those two compounds. This research actually preceded the discovery of the hormonal steroids by a good many decades. In view of their lack of biological activity, the investigations aimed at elucidating the structure of cholesterol and of cholic acid was probably undertaken largely as an exercise in structural organic chemistry. Results from these studies markedly facilitated subsequent efforts to assign structures to the so-called sex steroids.

1.1 Structure Determination

1.1.1 Cholesterol and Cholic Acid

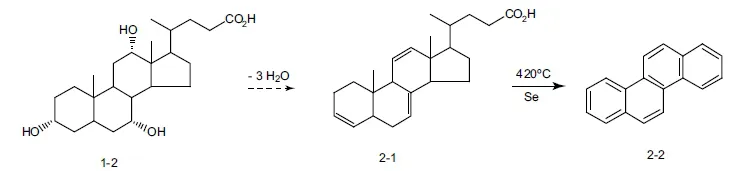

The research aimed at determining the chemical structure of steroids long predated the availability of the instruments that form the backbone of today’s work on the determination of the structures of natural products. Although the concept of infrared absorption had already been proposed in the mid-1920s, instruments for determining spectra would not be available until several decades in the future. The phenomenon of nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) was unknown even to theoretical physicists. Had the concept been proposed, the use of that tool in structural studies awaited the invention of magnetron vacuum tubes as sources of microwave radiation (development of that electronic device was as a direct product of wartime (World War II) research on radar). In the first half of the 20th century, work on structure determination instead relied largely on degradation reactions that would reduce the target to ever smaller molecules until they matched compounds of known structure. The work also relied extensively on combustion analysis for determining elemental composition and Rast molecular weight determinations. Isolation of discrete products from degradation reaction mixtures required great technical skill in those days before the advent of any sort of chromatography. Elegant chemical reasoning played a very large role in interpreting the results of degradation experiments. As an example, the major product from heating the triene 2-1 (Scheme 1.2), likely obtained from dehydration of cholic acid (1-2), consists of the hydrocarbon chrysene (2-2), the structure of which had by then been independently established. This result provided early evidence for the presence in steroids of a staggered array of four fused rings.

More direct evidence for the gross structure of carbon skeleton of steroids came from the isolation of the hydrocarbon 3-1 (Scheme 1.3) from a mixture of hydrocarbons obtained from heating cholesterol itself with selenium. This product 3-1, known as the Diels hydrocarbon, proved to be identical with a sample of the compound synthesized from starting materials of known structure by an unambiguous reaction scheme.

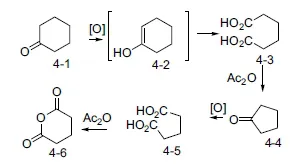

The size of each of the rings present in steroids was established by serial oxidation reactions starting with what would later be dubbed ring A. The empirical, so-called Blanc, rule holds that oxidation of a cyclohexanone (4-1) (Scheme 1.4) proceeds to afford a dicarboxylic acid (4-3), likely through the enol form, 4-2. Heating the diacid 4-3 with acetic anhydride proceeds to cyclopentanone 4-4 with loss of one carboxyl carbon. Repeated oxidation of that intermediate again results in a dicarboxylic acid, in this case adipic acid (4-5). Exposure to hot acetic anhydride leads to anhydride 4-6. The strained nature of the cyclobutanone that would result from cyclization as in 4-3 is disfavored over the formation of the anhydride. Reaction thus proceeds to succinic anhydride (4-6). In the absence of instruments, anhydrides can be distinguished from ketones by the fact that the former will lead to a dicarboxylic acid on basic hydrolysis. The neutral ketone can be recovered unchanged under the same conditions.

In the case of the reduced derivative of cholesterol, 5-1 (Scheme 1.5), the initial oxidation goes to the highly substituted adipic acid 5-2. The observation that this leads to a cyclopentanone (5-3) can be inferred to indicate that the ring at the start of the scheme was six-membered, Further oxidation of the cyclopentanone again leads to a dicarboxylic acid. On treatment with acetic anhydride, that intermediate leads to a cyclic anhydride. This leads to the inference that the precursor 5-3 was a cyclopentanone.

Serendipity played a role in establishing the structure of the side chain in cholesterol. Some investigators had noted that a sweet, perfume-like odor accompanied the vigorous oxidation of cholesterol acetate (6-1) (Scheme 1.6). The odorous substance was finally isolated from averylarge-scale (500 g) oxidation run and converted to its semicarbazone. This proved to be identical with the same derivative from 6,6-dimethylhexan-2-one (6-2).

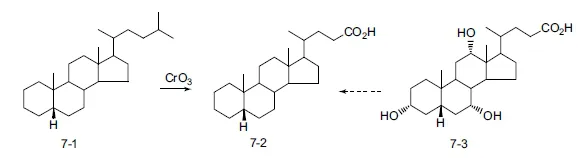

Many chemists, principally those in Adolf Windaus’s group at the University of Gottingen, worked on unraveling the intricacies of the structures in the cholesterol series. Another group, led by Heinrich Wieland at the University of Munich, studied the structures of the bile acids. Suspecting that these two natural products shared a common carbon nucleus, they each sought to relate the two by preparing a common derivative. In brief, they established that the cholanic acid 7-2 from exhaustive reduction of cholic acid (7-3) was identical to the product from oxidation of coprostane (7-1) (Scheme 1.7). The latter was obtained by exhaustive reduction of cholesterol. The common derivative, it should be noted, incorporates the less common cis A−B ring fusion. The reactions that lead to the common intermediate are unlikely to alter the configuration of chiral centers present in the natural products. The identity of the derivatives obtained from each starting material thus established that the product related to cholesterol and those derived from bile acids shared the same nucleus and overall stereochemistry.

The two groups and also other investigators who worked on the problem felt that enough data had been accumulated to propose a structure in 1928. Most of the carbonatoms had been accounted for and the results, they deemed, supported 8-1 (Scheme 1.8) as the structure of cholesterol. Some ambiguity existed as to the attachment of one of the two methyl groups in cholesterol. Some, it is said, referred to this fragment as the ‘floating methyl’. Depiction of the proposed structure in three dimensions (8-2), instead of the common two-dimensional notation (8-1), makes it clear that the proposed structure would have consisted of a relatively thick, congested molecule.

The use of X-ray crystallography for solving the structures of organic compounds was still in its infancy in the late 1920s. The use of that tool was hindered by the need to perform an enormous amount of data reduction; the mechanical calculating machines employed for that were then just coming into wider use. Atom-by-atom mapping of a complex structure such as a steroid was, atthattime, still beyond the then state-of-the-art. Resolution of an X-ray crystallographic study of ergosterol (8-3) was however sufficient to indicate that this steroid consisted of along, flat molecule (8-4) rather than a thick, congested entity such as 8-2. Re-examination of all the data from degradation studies revealed that an exception to the Blanc rule caused assignment of the wrong structure(8-2)to ergosterol. This second look also ledto the correct formulation of the steroid nucleus as depicted by 8-3.

One set of degradation studies on cholanic acid (9-1) (Scheme 1.9) led to scission of what are now known as ring A and ring C. One pair of the four new carboxylic acids led to a cyclopentanone and the other to an anhydride. On the basis of this, it was then inferred that ring A was six-membered whereas ring C comprised acyclopentane (see also 8-1). Itwas later recognized that carboxylic acids attached directly to rings as in 9-2 cannot form a cyclopentanone. This exception was later attributed to steric strain in the hypothetical product.

1.1.2 The Sex Steroids

By the early 1930s, it was clear that the reproductive function in mammals was directed by a group of potent discrete chemical substances. These compounds, dubbed sex hormones, consist of three distinct classes, the estrogens, the progestins and the androgens; these substances differ from each other in both biological activity and structure. The very small amounts of these compounds found in tissues posed a major challenge to investigations aimed at defining their chemical structure.

1.1.2.1 Estrogens

The first of the three classes of hormones that regulate reproductive function in both females and males of the species, the estrogens, progestins and androgens, were isolated in 1929. This marked contrast to the dates for the first isolation of bile acids and of cholesterol is due in no small part to the minute amounts of those hormones that were available for structural studies. Isolation of those substances from mammalian sources, such as mare’s urine, was guided by bioassays, increasing potency of a sample signaling higher purity. This work culminated in the isolation in 1929 of a weakly acidic compound, estrone (10-1) (Scheme 1.10). The acidity indicated the presence in the molecule of a phenol and hence an aromatic ring. Various chemical tests pointed to the steroid nature of estrone and also several closely related compounds. The principal accompanying compound, estradiol (10-2), and estrone comprise the primary estrogens and are freely intraconvertible both in vivo and in vitro. The former occurs as two isomers that differ at position 17; one iso...