- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

About this book

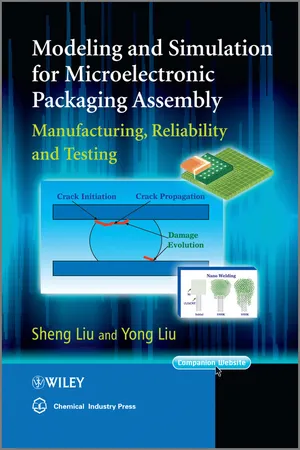

Although there is increasing need for modeling and simulation in the IC package design phase, most assembly processes and various reliability tests are still based on the time consuming "test and try out" method to obtain the best solution. Modeling and simulation can easily ensure virtual Design of Experiments (DoE) to achieve the optimal solution. This has greatly reduced the cost and production time, especially for new product development. Using modeling and simulation will become increasingly necessary for future advances in 3D package development. In this book, Liu and Liu allow people in the area to learn the basic and advanced modeling and simulation skills to help solve problems they encounter.

- Models and simulates numerous processes in manufacturing, reliability and testing for the first time

- Provides the skills necessary for virtual prototyping and virtual reliability qualification and testing

- Demonstrates concurrent engineering and co-design approaches for advanced engineering design of microelectronic products

- Covers packaging and assembly for typical ICs, optoelectronics, MEMS, 2D/3D SiP, and nano interconnects

- Appendix and color images available for download from the book's companion website

Liu and Liu have optimized the book for practicing engineers, researchers, and post-graduates in microelectronic packaging and interconnection design, assembly manufacturing, electronic reliability/quality, and semiconductor materials. Product managers, application engineers, sales and marketing staff, who need to explain to customers how the assembly manufacturing, reliability and testing will impact their products, will also find this book a critical resource.

Appendix and color version of selected figures can be found at www.wiley.com/go/liu/packaging

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Foreword by C. P. Wong

- Foreword by Zhigang Suo

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- About the Authors

- Part I: Mechanics and Modeling

- Part II: Modeling in Microelectronic Packaging and Assembly

- Part III: Modeling in Microelectronic Package Reliability and Test

- Part IV: Modern Modeling and Simulation Methodologies: Application to Nano Packaging

- Index

Frequently asked questions

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app