eBook - ePub

Problem-based Approach to Gastroenterology and Hepatology

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Problem-based Approach to Gastroenterology and Hepatology

About this book

Taking the problem-based approach, this text helps clinicians improve their diagnostic and therapeutic skills in a focused and practical manner. The cases included demonstrate the diversity of clinical practice in the specialty worldwide, and are divided into five major sections: Upper GI, Pancreato-Biliary, Liver, Small and Large Bowel, and Miscellaneous.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Problem-based Approach to Gastroenterology and Hepatology by John N. Plevris, Colin Howden, John N. Plevris,Colin Howden in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Gastroenterology & Hepatology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

PART ONE: Gastroenterology

1

Dysphagia

Dysphagia refers to difficulty or inability in swallowing food or liquids. Most dysphagia patients are candidates for urgent upper digestive endoscopy, to exclude the presence of esophageal cancer. The annual incidence of upper gastrointestinal malignancy, particularly esophageal adenocarcinoma, is steadily increasing in the western world, being the 5th most common primary site in Scotland [1].

Traditionally, dysphagia has been classified as oropharyngeal or esophageal. Oropharyngeal dysphagia is due to impaired food bolus formation or propagation into hypopharynx. Causes include neuromuscular disorders, cerebrovascular events, mechanical obstruction in the oral cavity or hypophanynx, decreased salivation, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s disease or depression. Esophageal dysphagia can be due to mechanical obstruction, (benign or malignant stricture), dysmotility disorders or secondary to gastro-esophageal reflux. Significant dysphagia is often associated with aspiration pneumonia.

A detailed history is important to elicit a possible etiology. In younger patients dysmotility is more common. The presence of chest pain during swallowing strongly suggests esophageal spasm; dysphagia for both liquids and solids is common is achalasia. In young patients with food impaction eosinophilic esophagitis should always be considered. In the elderly, neurological causes should be considered if the dysphagia is high, while esophageal cancer usually presents with short duration progressive dysphagia for solids with regurgitation and weight loss. New onset hoarse voice and dysphagia, point towards malignant infiltration of the recurrent laryngeal nerve. High dysphagia associated with regurgitation of undigested food from previous days, is strongly suggestive of a pharyngeal pouch.

Despite the different presenting features associated with different causes of dysphagia, there is no reliable way to predict at presentation those patients likely to have a malignant cause. Recently, a scoring system based on 6 parameters (advanced age, male gender, weight loss of >3 kg, new onset dysphagia, localisation to the chest and absence of acid reflux at presentation) could strongly predict malignancy [2]. In this chapter, three selected cases will illustrate the different etiologies of this important alarm symptom.

Case 1: Dysphagia for Liquids and Solids

Case Presentation

A 52-year-old man reports a 9-month history of difficulty swallowing both liquids and solids with meals and localizes the problem to upper sternum. He gets frequent episodes of coughing and choking when lying flat at night after meals. More recently, he has noticed spontaneous regurgitation of clear, foamy liquid and undigested food into his mouth, especially when bending over after dinner. He has lost over 15 lb (6.8 kg) since his symptoms began. Heartburn, which had been a problem in the past, has notably improved since his dysphagia began. Additional complaints include episodes of squeezing pain lasting for several minutes to 1 hour without radiation that can occur at any time and are unrelated to physical activity or meals. Drinking cold water sometimes alleviates the pain.

Past medical history: hypertension

Medications: lisinopril

Social history: employed as a businessman. Moved to the USA from Bolivia 20 years ago. Smokes 20 cigarettes per day. Drinks 3–4 glasses of wine per week

Family history: no family history of cancer or swallowing disorders

Physical examination: unremarkable

In particular, oral cavity without mucosal abnormalities, intact dentition, with no neck masses, lymphadenopathy or goiter. No evidence of sclerodactyly or telangiectasia.

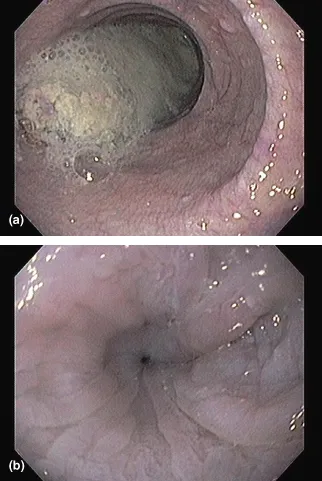

Upper endoscopy revealed a dilated esophagus with approximately 200 mL of retained, semisolid debris despite a 36-hour liquid diet (Figure 1.1a). The underlying mucosa appeared with scattered superficial erosions and mild, diffuse nodularity. Constriction of the esophagogastric junction was noted with minimal resistance to passage of the endoscope into the stomach (Figure 1.1b). Pylorus was patent and the duodenum was normal.

Figure 1.1 Endoscopic images of the esophagus: (a) a moderately dilated esophageal body with retained food and secretions in spite of a 12-hour fast; (b) a constriction at the level of the esophagogastric junction in the same patient.

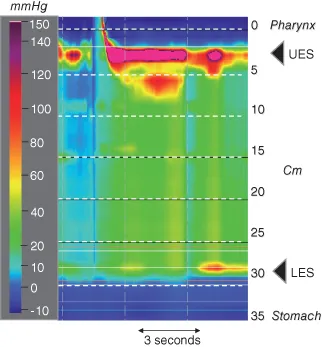

Esophageal manometry was performed using a high-resolution, solid-state catheter assembly with contour pressure topography (Figure 1.2) showed panesophageal pressurization or common cavity phenomenon in response to a water swallow. Failed deglutitive relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter was evident. The presence of an esophagogastric pressure gradient is seen in the esophagus before the swallow suggestive of achalasia.

Figure 1.2 High-resolution esophageal manometry pressure contour plot depicting a water swallow. Panesophageal pressurization above intragastric pressure is seen and failed lower esophageal sphincter relaxation is evident.

Questions

- What are the diagnostic considerations in this patient?

- What are the clinical symptoms of achalasia?

- What diagnostic tests are useful in achalasia?

- What is the pathophysiology of achalasia?

- What are the benefits and risks of different treatment options that should be discussed with this patient?

- What are the complications of achalasia?

Differential Diagnosis

Esophageal dysmotility should be considered in any patient presenting with dysphagia for both liquids and solids. A few caveats to this rule exist:

- First, patients with oropharyngeal dysphagia may present with liquid and solid dysphagia and, in fact, may have greater difficulty with liquids than solids. However, the fact that this patient localizes his dysphagia to the sternal area excludes an oropharyngeal etiology.

- Second, patients with esophageal food impaction typically have difficulty swallowing liquids and even their own saliva. However, the history was not consistent with repeated food impactions in this case.

- Third, the dysphagia that accompanies an advanced esophageal malignancy produces progressive obstruction. Although a consideration here, such patients present with a more rapid transition from solid to semisolid to liquid dysphagia over time.

The three major esophageal motor disorders are achalasia, scleroderma, and diffuse esophageal spasm (DES). Patients with scleroderma have typically mild dysphagia and in most cases is accompanied with cutaneous manifestations. Although both DES and achalasia are possible diagnoses in this patient, dysphagia in DES is generally less severe and more intermittent than in achalasia.

Clinical Presentation of Achalasia

Achalasia is an uncommon but important disease. The clinical manifestations as well as treatment center on the integrity of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES). Dysphagia and regurgitation are the most commonly reported symptoms. Nocturnal regurgitation can lead to night cough and aspiration. With progressive disease weight loss can occur. Chest pain is well recognized in achalasia and has been reported in 17–63% of patients but its mechanism is unclear although proposed etiologies include secondary or tertiary esophageal contractions, esophageal distension by retained food, gastro-esophageal reflux, esophageal irritation by retained medications, food, and bacterial or fungal overgrowth. Paroxysmal pain may be neuropathic in origin. Inflammation within the esophageal myenteric plexus could also be a contributory factor. More than one mechanism is likely operative in an individual patient.

A prospective study found no association between the occurrence of chest pain and either manometric or radiographic abnormalities [3]. Patients with chest pain were younger and had a shorter duration of symptoms compared with patients with no pain, but treatment of achalasia had little impact on the chest pain, in spite of adequate relief of dysphagia. Counter to this, a recent surgical series reported adequate relief of chest pain after a Heller myotomy [4]. Importantly, chest pain is not a universal feature in achalasia. In fact, many patients appear unaware of either esophageal distension or the prolonged the prolonged esophageal retention of food. Recent studies using esophageal barostat stimulation have demonstrated that some patients with achalasia have diminished mechanical and chemosensitivity of the esophagus [5]. Such differences may explain the heterogeneity of visceral sensitivity in the achalasia population.

Diagnostic Evaluation

Upper endoscopy is the first line investigation in suspected achalasia. Findings include esophageal dilation with retained saliva or food and annular constriction of the gastroesophageal junction. Intubation of the stomach is achieved with minor resistance due to raised LES pressure. Significant difficulty passing an endoscope through the gastroesophageal junction should raise the index of suspicion for pseudoachalasia due to neoplastic infiltration of the distal esophagus or gastric cardia. In spite of these recognized endoscopic features, upper endoscopy was reported as normal in 44% of a series of newly diagnosed achalasia patients [6]. A barium esophagogram (swallow) can be highly suggestive of achalasia, particularly when there is the combination of esophageal dilation with retained food and barium, and a smooth, tapered constriction of the gastroes...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- Contributors

- PART ONE: Gastroenterology

- PART TWO: Hepatology and Pancreatobiliary

- Index