![]()

PART ONE

THE BASICS

![]()

CHAPTER ONE

APPROACHING OUTCOMES

A horizon is nothing but the limit of our sight

—Rossiter Raymond

CHAPTER HIGHLIGHTS

- Outcomes: The Third Stage of Management

- Contrasting the Outcomes Approach with:

- The Problem Approach

- The Activity Approach

- The Process Approach

- The Vision Approach

For all the attention on outcomes in the social sector today, the casual observer might be tempted to think that the idea of outcomes and management toward them is self-evident and something that practitioners easily understand, adopt, and use in many or most of the facets of their programs or organizations. Experience, however, tells us a different story, because the fact is that the outcomes idea is not only a relatively recent arrival on the management scene, but that it also runs counter to the ways in which many people and organizations traditionally think about and approach problems, challenges, and even opportunities. To introduce people to the concept of outcomes, therefore, it is often helpful to begin by putting the ideas of outcomes and outcome management into a context that shows not only their evolutionary origin, but also their contrast to some traditional ways of thinking.

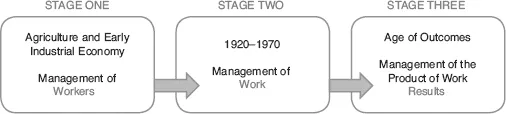

To understand the concept of outcomes as a tool, it sometimes helps to think of it as the Third Stage of Management and to compare it to what went before.

The First Stage, the oldest, and one that stretches literally back to the dawn of civilization, was the management of workers. In agricultural and early industrial societies, the only management possible was of the workers, who performed the manual and human-powered labor upon which society relied. There were strong workers and weak ones, reliable ones and unreliable ones, smart ones and dull-witted ones. Management meant managing these people, seeking the strongest, smartest, and most reliable workers. Beyond this, the only thing a manager could do to increase production was to get his people to work longer, faster, or harder . . . either that or add more workers. The idea of productivity as we understand it today had not yet been developed, and, in fact, was not even used in the English language to refer to work until 1898!1

While workers still needed to be managed—obviously necessary, as significant manual and physical labor still remained in the U.S. production system—much of this traditional focus on workers changed during the end of the 1800s and the early 1900s, as the Second Stage of Management dawned. There were two main influences on this development. The first was the appearance of the first truly national commercial systems . . . primarily the railroads. When long distance rail systems first began to emerge in the mid-nineteenth century, they faced problems of organization, administration, and discipline that had never been encountered before by any private enterprise.2 Crucial to the running of such a complex organization was attention to procedure expressly designed to minimize any potential for mishap or miscommunication: Hierarchies of authority were rigid, and procedures and the chain of command strict and unambiguous.3 It was the beginning of what we would come to call a focus on process.

In the early 1900s, when Frederick Taylor defined and began implementing his theories of Scientific Management, this accent on how things were done continued and gained new stature and acceptance. Taylor’s insight was that there might be something about the work itself that could be improved upon. His management method sounded deceptively simple: First, look at a task and analyze its constituent motions. Next, record each motion, the physical effort it takes, and the time it takes. Motions not absolutely needed would be eliminated, and what remained would represent the simplest, fastest, and easiest way to obtain the finished product. Within a decade of Taylor’s initial work, the productivity of manual labor began its first real rise in history, and continues to rise to this day.4 Henry Ford’s legendary assembly line was merely an extension of Taylor’s principles, Ford’s contribution being the limitation of one constituent motion (continually repeated) per worker along the line.

It was not long, however, before Ford and other manufacturing barons realized that, despite appearances, they were not actually in the business of making cars, thimbles, shoes, or widgets. Rather, they were in the business of selling those cars, thimbles, shoes, and widgets . . . and unless those products met consumer needs, tastes, and expectations, the barons realized, they would not be in business for long. This was the beginning of a radical shift in thinking away from the traditional concepts of success, previously defined mostly in terms of “more” (more flour milled, more yards of textile produced, more widgets made) and toward the elusive notion of “better.”

Outcomes: The Third Stage of Management

Gaining strength with the modern post-industrial economy, as more and more work involved less and less physical labor, the accent of management shifted from work to performance.5 For this shift to be complete, however, the starting point had to be a new definition of “results,” for it was the results and not the work itself that now had to be managed.6 In other words, if we want better, we must first define what better is.

Of course, manufacturing steps and processes that continued to require manual labor still received the attention of management thinkers. But the new accents on the finished product and “better,” and their influence on customer buying decisions was the key to a new perspective that allowed for the eventual development of Outcome Thinking, because it was the beginning of an examination of outcomes and of the Third Stage of Management—the management of results.

Exercise

In the spaces below, think of your program or organization. First, think in terms of how you manage any staff who work under you. What are the things you consider and do? Write them down in the space below. Next, think of the work this staff does. In the adjacent space, write down the things you consider and do to manage their work and workflow. Finally, in the third space, think of the outcomes, targets, or goals your program or organization has, the quality question concerning your program or organization’s outputs. In the adjacent space, write down the things you think you might consider or do to manage toward those ends.

MANAGING WORKERS

MANAGING WORK

MANAGING RESULTS

But appreciating where Outcome Thinking came from, how it evolved, and how it differs from what went before does not really tell us what it is as a discipline. We are still forced to ask, What is an outcomes approach? How does an outcomes mind set differ from the ways most people naturally and instinctively approach challenges, situations, programs, and projects? Maybe the best way to answer this question is to start by offering examples of other approaches as a contrast, to better illustrate what makes up a truly outcomes mind set.

As you read these examples, keep in mind that few people or organizations use any one of them exclusively or all the time. Instead, most individuals and organizations, particularly those who have never practiced applying an Outcomes Approach to situations, seem to naturally fall back on two or three accustomed, comfortable, and almost instinctive methods for facing situations, analyzing them, and responding to them. More to the point, most people and organizations will keep reacting in these ways, even if these responses do not bring about desired results, unless they are shown and come to believe in a better way to meet and respond to challenges and new situations.

We’ll call these examples the Problem Approach, the Activity Approach, the Process Approach, and the Vision Approach.

The Problem Approach

The Problem Approach to challenges is a natural and difficult-to-avoid perspective that focuses most of its attention on what is wrong with a given situation, how big or bad the situation is, who or what is responsible for the negative condition, how much work needs to be done to fix things, and what stands in the way of applying that fix. Because of this, the questions the Problem Approach triggers tend to be Why do we have this problem? What or who caused it? and What obstacles exist to solving it?

Martin Luther King Jr.’s greatest speech was not called “I Have a Complaint”

—Van Jones

While the Problem Approach does often lead to answering the Why? questions—an important consideration where there is a person or entity that can be held liable for remediation of the problem—and while it can serve as a short-term motivator by operating upon people’s sense of outrage and injustice, it can also be a trap. A focus on the enormity of the problem, the insurmountable nature of obstacles standing in the way of correcting it, and the Problem Approach’s tendency of keeping us focused on blame can all be depressing and demotivating. Most importantly, however, the Problem Approach often limits our ability to envision success, and the outcomes that describe it, in any terms other than that the problem no longer exists. As an example, faced with a population of children who cannot read, the Problem Approach (after fixing responsibility on the host of...