![]()

Part One

Theoretical Basis

![]()

Chapter 1

Introduction

This book assumes that the reader has basic knowledge of wireless communications, including different types of wireless links, an understanding of the physical layer concepts, familiarity with medium access control (MAC) layer role, and so on. The reader is also expected to have a grasp of computer networks protocol stack layers, the Open System Interface (OSI) model, and some detailed knowledge of the network layer and its evolution to Internet Protocol (IP) with protocols such as Open Shortest Path First (OSPF) in addition to Transmission Control Protocol (TCP) and User Datagram Protocol (UDP) over IP. Also, some knowledge of topics such as queuing theory is assumed. In the first part of this book, we will review some of these topics in the context of the tactical wireless communications and networking field before we cover the specifics of the field.

One can divide engineers and scientist in the field of tactical wireless communications and networking into two main groups. One group emphasizes the physical layer and dives into topics such as modulation techniques, error control coding at the data link layer (DLL), and the air interface resource management, and so on. The second group emphasizes networking protocols diving into the network layer, the transport layer, and applications. The first group, primarily composed of electrical engineers, likes to build radios assuming that everything above the DLL that has to interface with the radio is commercial-off-the-shelf (COTS). The second group, mostly composed of computer scientists, assumes that everything below the network layer is just a medium for communications. This book will explain tactical wireless communications and networking in a balanced manner, covering all protocol stack layers. This will provide the reader with a complete overarching view of both the challenges and the design concepts pertaining to tactical wireless communications and networking.

The evolution of tactical wireless communications and networks followed a significantly different path from that of commercial wireless communications and networks. A major milestone of tactical wireless communications development occurred in the 1970s, with the move from the old push-to-talk radios to the first spread spectrum and frequency hopping radios (with anti-jamming capabilities). Since World War II, commanders and soldiers on the ground have effectively communicated with radios forming voice broadcast subnets. These subnets, with their small area of coverage, functioned independent of a core network. Over time, the core networks were created to link tactical command nodes to the command-and-control (C2) nodes and then to headquarters. Commanders on the ground carried push-to-talk radios to communicate with their soldiers and relied on communications vehicles to link them to their superiors through a circuit switched network with microwave or satellite links. Although enhanced versions of these technologies are still deployed today, this book will consider them as legacy architecture and “a thing of the past.” This text focuses on the Global Information Grid (GIG) vision where the tactical theater is full of IP-based subnets that communicate seamlessly to each other with network management policies that enforce the military hierarchy.

1.1 The OSI Model

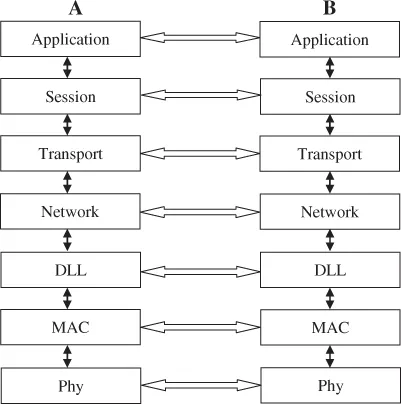

Every computer networking book, in one way or another, emphasizes the OSI model. The OSI model has its roots in the IBM definitions of networking computers from the early days. Defining such interfaces, while the science of computer networking was a new field, was an effective approach to accelerate the development of networking protocols. With the OSI model, there are different protocol stack layers, with each stack layer performing some predefined functions. These protocol stack layers are separated and utilize standard upward and downward interfaces. These layers work as separate entities and are peered with their corresponding layers in a remote node. Figure 1.1 demonstrates a conventional OSI with seven layers: the application layer, the session layer, the transport layer, the network layer, the DLL, the MAC layer, and the physical layer. These layers communicate to their peer layers (A and B are peer nodes) as shown by the horizontal arrows. Traffic flows up and down the stack, based on well-defined interfaces as indicated by the vertical arrows. Note that some text books may have different variations of these layers. For example, some textbooks may present a presentation layer under the application layer and before the session layer to perform data compression or encryption. Other models (especially for point-to-point links) omit the MAC layer, but we are especially interested in the MAC layer in this book since it is an important part of multiple-access tactical radios. Some models also refer to the IP layer as a network sub-layer. Here, we consider the IP layer as the network layer using IP. Regardless of these variations of the OSI model, the wide use of IP today has created a standard network layer with standard interfaces below it (IP ports to radios, point-to-point links, multiple access wired subnets such as Ethernet, optical links, etc.) and IP ports above clients, servers, voice over IP (VoIP), video over IP, and so on.

Let us summarize the OSI model before we jump into the tactical wireless communications and networking open architecture model. You can refer to other computer networking books to read more about the OSI model details.

The application layer is simply a software (SW) process that performs its intended application. Your e-mail is a simple example of an application process that runs on your PC or phone (which is essentially a network node).

The session layer has roots in the plain old telephony (POT) networks where call connection information is given to the transport layer. Today, the session layer could be used for authentication, access rights, and so on.

The transport layer can be understood as two peer processors (in nodes A and B in Figure 1.1) that perform the following necessary functions:

- Break messages down into packets when transmitting, and reassemble when receiving.

- If the layer...