- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Articulatory Phonetics

About this book

Articulatory Phonetics presents a concise and non-technical introduction to the physiological processes involved in producing sounds in human speech.

- Traces the path of the speech production system through to the point where simple vocal sounds are produced, covering the nervous system, and muscles, respiration, and phonation

- Introduces more complex anatomical concepts of articulatory phonetics and particular sounds of human speech, including brain anatomy and coarticulation

- Explores the most current methodologies, measurement tools, and theories in the field

- Features chapter-by-chapter exercises and a series of original illustrations which take the mystery out of the anatomy, physiology, and measurement techniques relevant to speech research

- Includes a companion website at www.wiley.com/go/articulatoryphonetics with additional exercises for each chapter and new, easy-to-understand images of the vocal tract and of measurement tools/data for articulatory phonetics teaching and research

- Password protected instructor's material includes an answer key for the additional exercises

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Part I

Getting to Sounds

Chapter 1

The Speech System and Basic Anatomy

Sound is movement. You can see or feel an object even if it – and everything around it – is perfectly still, but you can only hear an object when it moves. When things move, they sometimes create disturbances in the surrounding air that can, in turn, move the eardrum, giving us the sensation of hearing (Keith Johnson’s Acoustic and Auditory Phonetics discusses this topic in detail). In order to understand the sounds of speech (the central goal of phonetics as a whole), we must first understand how the different parts of the human body move to produce those sounds (the central goal of articulatory phonetics).

This chapter describes the roadmap we follow in this book, as well as some of the background basics you’ll need to know.

1.1 The Speech Chain

Traditionally, scientists have described the process of producing and perceiving speech in terms of a mostly feed-forward system, represented by a linear speech chain (Denes and Pinson, 1993). A feed-forward system is one in which a plan (in this case a speech plan) is constructed and carried out, without paying attention to the results. If you were to draw a map of a feed-forward system, all the arrows would go in one direction (see Figure 1.1).

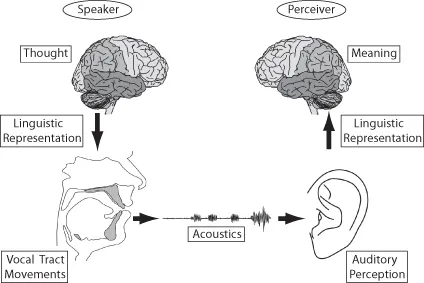

Figure 1.1 Feed-forward, auditory-only speech chain

(image by W. Murphey and A. Yeung).

Thus, in a feed-forward speech chain model, a speaker’s thoughts are converted into linguistic representations, which are organized into vocal tract movements – articulations – that produce acoustic output. A listener can then pick up this acoustic signal through hearing, or audition, after which it is perceived by the brain, converted into abstract linguistic representations and, finally, meaning.

Although the simplicity of a feed-forward model is appealing, we know that producing speech is not strictly linear and unidirectional. Rather, when we speak, we are also constantly monitoring and adjusting what we’re doing as we move along the chain. We do this by using our senses to perceive what we are doing. This is called feedback. In a feedback system, control is based on observed results, rather than on a predetermined plan. The relationship between feedforward and feedback control in speech is complex. Also, speech perception feedback is multimodal. That is, we use not just our sense of hearing when we perceive and produce speech, but all of our sense modalities – even some you may not have heard of before. Thus, while the speech chain as a whole is generally linear, each link in the chain – and each step in the process of speech communication – is a loop (see Figure 1.2). We can think of each link of the chain as a feedback loop.

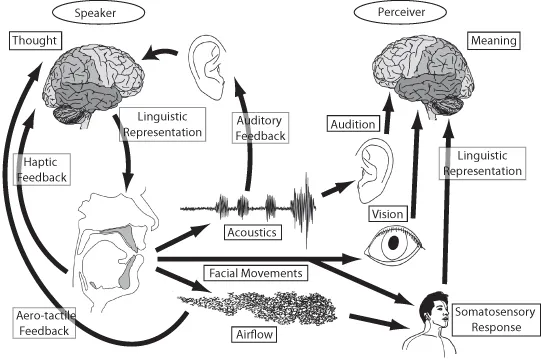

Figure 1.2 Multimodal speech chain with feedback loops

(image by W. Murphey and A. Yeung).

Multimodality and Feedback

Speech production uses many different sensory mechanisms for feedback. The most commonly known feedback in speech is auditory feedback, though many senses are important in providing feedback in speech.

Speech is often thought of largely in terms of sound. Sound is indeed an efficient medium for sharing information: it can be disconnected from its source, can travel a long distance through and around objects, and so on. As such, sound is a powerful modality for communication. Likewise, auditory feedback from sound provides a speaker with a constant flow of feedback about his or her speech.

Speech can also be perceived visually, by watching movements of the face and body. However, because one cannot normally see oneself speaking, vision is of little use for providing speech feedback from one’s own articulators.

The tactile, or touch, senses can also be used to perceive speech. For example, perceivers are able to pick up vibrotactile and aero-tactile information from others’ vibrations and airflow, respectively. Tactile information from one’s own body can also be used as feedback. A related sense is the sense of proprioception (also known as kinesthetic sense), or the sense of body position and movement. The senses of touch and proprioception are often combined under the single term haptic (Greek, “grasp”).

1.1.1 The Speech Production Chain

Because this textbook is about articulatory phonetics, we’ll focus mainly on the first part of the speech chain, just up to where speech sounds leave the mouth. This part of the chain has been called the speech production chain (see Figure 1.3). For simplicity’s sake, this book will use a roadmap that follows along this feed-forward model of speech production, starting with the brain and moving in turn through the processes involved in making different speech sounds.

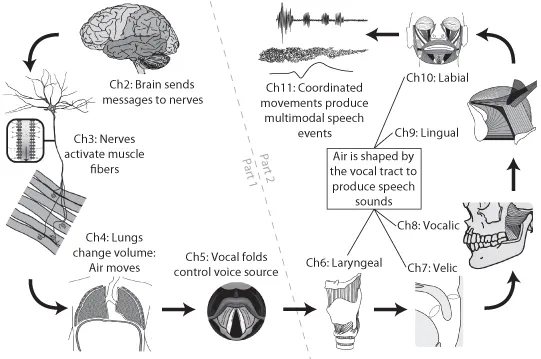

Figure 1.3 Speech production chain; the first half (left) takes you through Part I of the book, and the second half (right) covers Part II

(image by D. Derrick and W. Murphey).

This is often how we think of speech: our brains come up with a speech plan, which is then sent through our bodies as nerve impulses. These nerve impulses reach muscles, causing them to contract. Muscle movements expand and contract our lungs, allowing us to move air. This air moves through our vocal tract, which we can shape with more muscle movements. By changing the shape of our vocal tract, we can block or release airflow, create vibrations or turbulence, change frequencies or resonances, and so on, all of which produce different speech sounds. The sound, air, vibrations and movements we produce through these actions can then be perceived by ourselves (through feedback) or by other people as speech.

1.2 The Building Blocks of Articulatory Phonetics

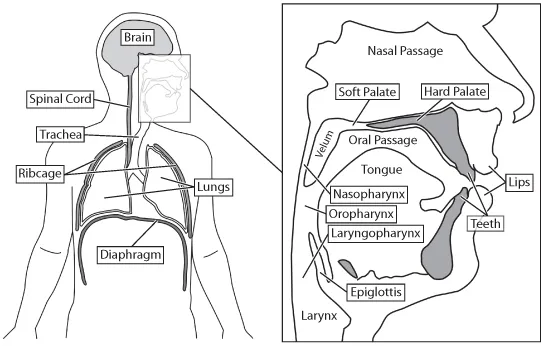

The field of articulatory phonetics is all about the movements we make when we speak. So, in order to understand articulatory phonetics, you’ll need to learn a good deal of anatomy. Figure 1.4 shows an overview of speech production anatomy. The speech production chain begins with the brain and other parts of the nervous system, and continues with the respiratory system, composed of the ribcage, lungs, trachea, and all the supporting muscles. Above the trachea is the larynx, and above that the pharynx, which is divided into the laryngeal, oral, and nasal parts. The upper vocal tract includes the nasal passages, and also the oral passage, which includes structures of the mouth such as the tongue and palate. The oral passage opens to the teeth and lips. The face is also intricately connected to the rest of the vocal tract, and is an important part of the visual and tactile communication of speech.

Figure 1.4 Anatomy overview: full body (left), vocal tract (right)

(image by D. Derrick).

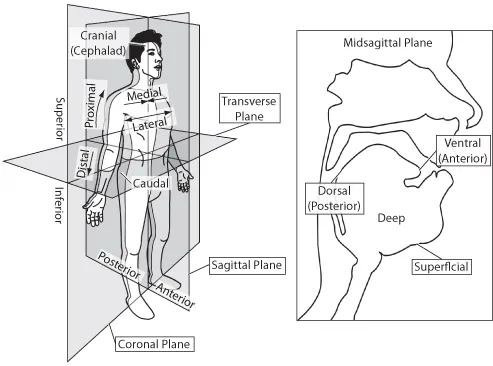

Scientists use many terms to describe anatomical structures, and anatomy diagrams often represent anatomical information along two-dimensional slices or planes (see Figure 1.5). A midsagittal plane divides a body down the middle into two halves: dextrad (Latin, “rightward”) and sinistrad (Latin, “leftward”). The two axes of the sagittal plane are (a) vertical and (b) anterior-posterior. Midsagittal slices run down the midline of the body and are the most common cross-sections seen in articulatory phonetics. Structures near this midline are called medial or mesial, and structures along the edge are called lateral.

Figure 1.5 Anatomical planes and spatial relationships: full body (left), vocal tract (right)

(image by D. Derrick).

Coronal slices cut the body into anterior (front) and posterior (back) parts. The two axes of the coronal plane are (a) vertical and (b) side-to-side.

The transverse plane is horizontal, and cuts a body into superior (top) and inferior (bottom) parts.

The direction of the head is cranial or cephalad, and the direction of the tail is caudal. Also, ventral refers to the belly, and dorsal refers to the back. So, for creatures like humans that stand in an upright position, ventral is equivalent to anterior, and dorsal is equivalent to posterior. There are also terms that refer to locations relative to a center point rather than planes. Areas closer to the trunk are called proximal, while areas away from the trunk, like hands and feet, are distal.

Finally, structures in the body can also be described in terms of depth, with superficial structures being nearer the skin surface, and deep structures being closer to the center of the body.

1.2.1 Materials in the Body

Anatomical structures are made up of several materials. Nerves make up the nervous system, and will be discussed in Chapters 2 and 3. As we are mostly interested in movement in this book, though, we’ll mainly be learning about bones and muscles.

The “hard parts” of the body are made up of bones and cartilages. Bony, or osseous material is the hardest. The skull, ribs, and vertebrae are all composed of bone. These bones form the support structure of the vocal tract. Cartilaginous or chondral (Greek, “cartilage, grain”) material is composed of semi-flexible material called cartilage. Cartilage is what makes up the stiff but flexible parts you can feel in your ears and nose. The larynx and ribcage contain several important cartilages for speech. Bones and cartilages are also the “hard parts” in the sense that you need to memorize their names, whereas most muscles are just named according to which hard parts th...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Articulatory Phonetics

- Title page

- Copyright page

- List of Figures

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction

- Part I: Getting to Sounds

- Part II: Articulating Sounds

- Abbreviations Used in this Book

- Muscles with Innervation, Origin, and Insertion

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Articulatory Phonetics by Bryan Gick,Ian Wilson,Donald Derrick in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Languages & Linguistics & Phonetics & Phonology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.