![]()

Chapter One

The Phases of Decline and Early Warning Signs

In December of 2009, six partners in the accounting firm Ernst & Young paid $8.5 million to settle long-standing charges that they failed to see problems at Bally Total Fitness. Bally had overstated its stockholders’ equity by $1.8 billion and had understated net losses in its business by approximately $100 million in each of several years. The company had recognized revenue it never actually received from initiation fees and prepaid dues. The partners were charged with failure to spot the warning signs at Bally as it slid from profitability to bankruptcy, but the firm itself paid an even higher price.

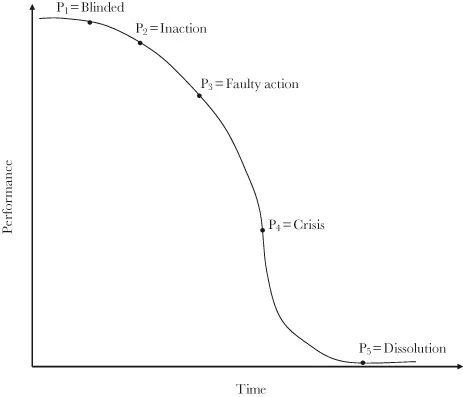

The longer such problems go unsolved, the harder it is to turn around a company. To determine the effort needed to turn around any organization, one must understand the degree of trouble and how quickly time is running out; an organizational distress curve illustrates this concept. To help determine where an organization is on the curve, there are early warning signs that signal to a board of directors, investors, and management that action is needed.

The Phases of Decline

Regardless of the cause or nature of a distressed company’s struggles, it will invariably find itself somewhere on the curve in Figure 1.1, which demonstrates how companies slide down a slippery slope through five phases: the blinded, inaction, faulty action, crisis, and dissolution phases.1 If the company cannot fix its problems in any one phase, they will eventually fall to the next one, with less time to repair the damage and greater effort required to do so.

Companies typically begin in the blinded phase. Revenues may have stagnated or even fallen off slightly, but in general, the company has not yet recognized the crisis. Management often writes off one bad quarter—or even two or more—as a blip, only too happy to assume that business will recover in the coming weeks or months. They attribute decreases in sales or profits to seasonal or cyclical variations or temporary customer fickleness, blissfully ignorant of the potentially impending catastrophe. Our examination of Electronic Data Systems in this chapter shows that EDS lay in the blinded phase for years when it overlooked the explosion in popularity of the client/server architecture that would undermine its core competency in the traditional mainframe architectures it served.

Companies in the blinded phase can languish there for months or even for years, as represented by the smooth slope of the curve there. If management fails to take corrective action, however, the company will eventually enter the inaction phase when growth continues to stagnate, competitors steal market share, or cash reserves begin to run low. The company is likely to remain fundamentally sound, and may even be profitable, but its problems have grown to the point at which they cannot be denied. Despite the clear need for action, however, companies often linger in the inaction phase, their inertial resistance to change inspiring irrational hope that things will turn around on their own. For example, Pier 1 took years to react to price competition from Wal-Mart and Target. Such managers often invoke images of past recessions weathered, crying, “This company has suffered through far worse than this,” hoping that their previous run of luck continues. The examination of the Middleby Corporation in Chapter Four will demonstrate a company in the inaction phase, as the manufacturer of diversified food equipment remained passive throughout the late 1990s despite excessive concentration of sales to a few very large customers and four years of investment in an expensive, unsuccessful product line.

Other examples of inaction include Schwinn management ignoring the growing consumer preference for lighter mountain bikes, insisting that “people want to ride bikes, not carry them.”2 IBM exhibited comparable denial, saying for years that the Internet was “a university thing.”3

Sometimes those companies do rebound, but they just as often do not, and instead slide further down the organizational distress curve into the faulty action phase. At this point, the company’s problems have grown in severity to the point that management is spurred to action, but due either to inaccurate information or incompetent leaders, these proposed remedies only make the situation worse.

It is not always easy to distinguish inaction from faulty action. A young friend and fellow turnaround professional who prided himself on fast action, once found himself on a new engagement as a chief restructuring officer (CRO) for a struggling company, and decided to take matters into his own hands. Convinced that employees at one of the plants had gotten lazy, he showed up unannounced during the night shift, determined to ferret out the malingerers. He was convinced his actions that night would solve all the company’s personnel problems.

He arrived just before the official break time and saw one young man leaning against the wall, daydreaming while everyone else worked arduously. Furious, the CRO demanded the plant manager stop all work and gather the employees together.

In his anger, he emptied his wallet, taking more than $400 in travel money and jamming it into the hands of the young man. “That,” he exclaimed, “is all you’ll get in severance pay. You wanna sue me? Go ahead! You’ll just lose all your legal bills. Get out. Now!”

The young man glanced around, hesitant and confused, and left. With great satisfaction, the CRO measured the shocked look on the other workers’ faces—precisely the desired reaction—before asking the plant manager, “What did that loafer do, anyway? The rest of these people should be able to take up the slack.”

“He was the pizza delivery guy,” the plant manager replied. “He was waiting for me to bring him a tip.”

The story quickly became legend among turnaround professionals.

By contrast, when Jamie Dimon took over as CEO of Bank One in Chicago, he sent a clearer, more effective message to the company’s executive team. The executive floor was undergoing an expensive renovation and interior decorating. Dimon ordered all work to stop, leaving several executive offices partly spackled or wallpapered for almost a year. That message rang loud and clear to all the bank’s employees: Dimon expected everyone to watch spending. His plan to avoid faulty action worked as he went on to take well-planned immediate action to reduce costs while increasing revenue through more responsive service to the bank’s customers.

Sara Lee’s failed turnaround efforts in 1997 and 2000 both represent faulty action, as the company remained decentralized in critical product and marketing efforts, causing inefficiencies in achieving scale in purchasing raw materials and winning retail space. Similarly, Blockbuster continued to open stores and even attempted to merge with Circuit City (which later liquidated in bankruptcy court), saying that customers wanted to visit stores to make movie rental decisions despite the growing success of the Netflix model. Borders (a spinoff from Kmart) thought the answer to Amazon was to expand their chain internationally, which proved a painfully regrettable decision. Both Blockbuster and Borders focused on continuing and even expanding their business model in the face of a changing competitive environment. They never reexamined their strategy or core competencies, methods described later in this book.

One most often finds faulty action when executives perform across-the-board downsizing without first reexamining the company’s strategy, reengineering, or seeking niche markets. These concepts are all discussed in later chapters.

Sustained faulty action will drive a company into the crisis phase. At this point, the company has probably tripped covenants with its lenders and is bleeding cash. Employees are jumping ship, suppliers insist on cash in advance or cash on delivery payment terms, and auditors raise genuine concerns about the company’s ability to continue as a going concern. Companies often retain an investment bank to “consider strategic alternatives,” or even direct their outside counsel to begin drafting documents for a bankruptcy filing. The examination of Winn-Dixie’s 2004 bankruptcy filing in Chapter Six will demonstrate a company “securely” in the crisis phase. American newspapers were also in the crisis phase for years, and still did nothing but cut the people that gather and create its content.

The crisis phase represents a company’s last chance to salvage itself and get back on course to profitability. Should all restructuring and turnaround efforts fail, it will descend into the fifth and final dissolution phase, which typically requires a bankruptcy filing. Unable to continue as a going concern, the company goes through painful changes or liquidates its assets and distributes them according to the absolute priority rule that is examined in Chapter Six. This is when the sheriff and locksmiths arrive.

These phases present a valuable framework, because study after study has shown that the earlier a company recognizes itself in one of these phases and launches a turnaround effort, the greater the likelihood of its success. As companies slide down the organizational distress curve, they find themselves in a rapidly tightening noose. In order to maintain breathing space for the greatest number of stakeholders, early detection through the monitoring of the warning signs detailed in this chapter in the section “Early Warning Signs” is critical. If a management team recognizes its problems and begins addressing them earlier, it can take action outside of an atmosphere of panic, before a cash crisis severely restricts its options and before employees, customers, and suppliers begin abandoning it.

Moreover, early detection allows a company to monetize assets at greater than fire sale prices. Whether they decide to pursue a sale of the entire company—perhaps to a “greater fool”—or simply sell a division or product line, management will invariably receive a better price if the market does not yet perceive them as distressed. Similarly, if management settles upon additional financing or refinancing as the solution, it will find lenders significantly more receptive to a company having only experienced mild setbacks rather than one in full-on crisis mode.

Perhaps most important, early action limits the likelihood of managers finding themselves personally liable to stakeholders for the mismanagement of the company. Many American courts hold that a board of directors’ fiduciary liabilities shift when a company enters a nebulously defined “zone of insolvency.” Some courts define the zone as when the market value of a company’s assets is less than its book value of liabilities. Others say it’s when the company cannot meet its debts when due. It exists when the organization is in the crisis phase even before hitting the dissolution phase on the distress curve.

Previously bound in their duties exclusively to equity holders, the board’s duties shift to include other stakeholders—most notably, to creditors and to the “entity”—once the company enters the zone of insolvency. Should the company subsequently enter bankruptcy, courts will examine transactions as much as five years prior to the filing, particularly those dealing with company insiders, and might possibly void such transactions as fraudulent or preferential. Even outside the context of a bankruptcy filing, the risk of director liability has grown in the past decade, with some institutional investors placing “bounties” on directors and officers by offering a much higher percentage contingency fee to lawyers for every dollar of recovery that comes out of the personal assets of corporate executives and directors who are named as individual defendants. The recent economic downturn and foolish acts by executives have even threatened to weaken that panacea of directors and officers accused of wrongdoing: the business judgment rule.

The business judgment rule used to protect almost every decision made, as it assumed each individual used his or her business knowledge, even if the result appeared stupid in hindsight. The officers and directors of Bally couldn’t use the business judgment defense, however, when they ignored the warning signs that the company’s policies of high-pressure sales tactics and changing accounting practices were leading to serious problems.

Enron’s directors also used the business judgment rule as their primary defense, saying they knew nothing of the deceit created by Ken Lay and his staff. That defense fell and the directors paid millions out of their own pockets when the institutional investors paid a bounty to contingency law firms for getting money out of the directors’ pockets rather than the company’s insurance policies. The motive was revenge for failing to do their jobs and watch for the warning signs.

At a meeting with institutional investors in late 2008, Justice Carolyn Berger of the Delaware Supreme Court suggested that she and her colleagues—the de facto standard for American business law given the concentration of companies incorporated in the state—would also consider limiting the protection afforded by the business judgment rule with respect to questions of executive compensation. This potential threat to executives of troubled companies, who after all, are the only ones typically sued for professional liability, makes it more important than ever to recognize the earliest possible warning signs of distress and take action immediately.

Early Warning Signs

In order to prevent these internal and external causes of distress from festering until it is too late, effective management teams must proactively look for potential challenges, because the sooner they are identified, the greater the likelihood that management can address them successfully. Companies should remain vigilant by using four major analyses: management analysis, trend analysis, industry ...