![]()

1

Purpose and Structure of Financial Markets

1.1 OVERVIEW OF FINANCIAL MARKETS

Financial markets play a major role in allocating excess savings to businesses in the economy. This desirable process takes various forms. Commercial banks take depositors’ money and lend it to manufacturers, service firms, or home buyers who finance new construction or improvements. Investment banks bring to market equity and debt offerings of newly formed or expanding corporations. Governments issue short- and long-term bonds to finance the construction of new roads, schools, and transportation networks. Investors (bank depositors and securities buyers) supply their funds in order to shift their consumption into the future by earning interest, dividends, and capital gains.

The process of transferring savings into investment involves various participants: individuals, pension and mutual funds, banks, governments, insurance companies, industrial corporations, stock exchanges, over-the-counter (OTC) dealer networks, and others. All these agents can, at different times, serve as demanders and suppliers of funds, or as intermediaries. Economic theorists ponder the optimal design of securities and institutions, where “optimal” implies the best outcomes – lowest cost, least disputes, fastest – for security issuers and investors, as well as for the society as a whole. Are stocks, bonds, or mortgage-backed securities, the outcomes of optimal design or happenstance? Do we need “greedy” investment bankers, securities dealers, or brokers? What role do financial exchanges play in today's economy? Why do developing nations strive to establish stock exchanges even though they often have no stocks to trade on them? Once we answer these basic questions, it will not be difficult to see why all the financial markets are organically the same. In product markets, the four-cycle radiator-cooled engine-powered car and the RAM memory-bus-hard disk personal computer have withstood the test of time. And so has the spot–futures–options, primary–secondary, risk transfer-driven design of the financial market. In the wake of the 2008 crisis we have seen very limited tweaks to the design, because it is so robust.

All markets have two separate segments: original issue and resale. These are characterized by different buyers, sellers, and different intermediaries, and they perform different timing functions. The first transfers capital from the suppliers of funds (investors) to the demanders of capital (businesses); the second transfers capital from the suppliers of capital (investors) to other suppliers of capital (investors). The two segments are:

- Primary markets (issuer-to-investor transactions with investment banks as intermediaries in the securities markets, and banks, insurance companies and others in the loan markets);

- Secondary markets (investor-to-investor transactions with broker-dealers and exchanges as intermediaries in the securities markets, and mostly banks in the loan markets).

All markets have the originators, or issuers, of the claims traded in them (the original demanders of funds) and two distinctive groups of agents operating as investors, or suppliers of funds. The two groups of funds suppliers have completely divergent motives. The first group aims to eliminate the undesirable risks of the traded assets and earn money on repackaging, the other actively seeks to take on those risks in exchange for uncertain compensation. The two groups are:

- Hedgers (dealers who aim to offset primary risks, be left with short-term or secondary risks, and earn spread from dealing);

- Speculators (investors who hold positions for longer periods without simultaneously holding positions which offset primary risks).

The claims traded in all financial markets can be delivered in three ways. The first is an immediate exchange of an asset for cash. The second is an agreement on the price to be paid with the exchange taking place at a predetermined time in the future. The last is a delivery in the future, contingent upon an outcome of a financial event, e.g. level of stock price or interest rate, with a fee paid up front for the right of delivery. The three market segments based on the delivery type are:

- Spot or cash markets (immediate delivery)

- Forward markets (mandatory future delivery or settlement)

- Options markets (contingent future delivery or settlement)

We focus on these structural distinctions to bring out the fact that all markets not only transfer funds from suppliers to users, but they also transfer risk from users to suppliers. They allow risk transfer or risk sharing between investors. The majority of the trading activity in today's market is motivated by risk transfer with the acquirer of risk receiving some form of certain or contingent compensation. The relative price of risk in the market is governed by a web of relatively simple arbitrage relationships that link all the markets. These allow market participants to assess instantaneously the relative attractiveness of various investments within each market segment or across all of them. Understanding these relationships is mandatory for anyone trying to make sense of the vast and complex web of today's markets.

1.2 RISK SHARING

All financial contracts, whether in the form of securities or not, can be viewed as bundles, or packages of unit payoff claims (mini-contracts), each for a specific date in the future and a specific set of outcomes. In financial economics, these are called state-contingent claims.

Let us start with the simplest illustration: an insurance contract. A 1-year life insurance policy promising to pay $1,000,000 in the event of the insured's death can be viewed as a package of 12 monthly claims (lottery tickets), each paying $1,000,000 if the holder dies during that month. The value of the policy up front (the premium) is equal to the sum of the values of all the individual tickets. As the holder of the policy goes through the year, he can discard tickets that did not pay off, and the value of the policy to him diminishes until it reaches zero at the end of the coverage period.

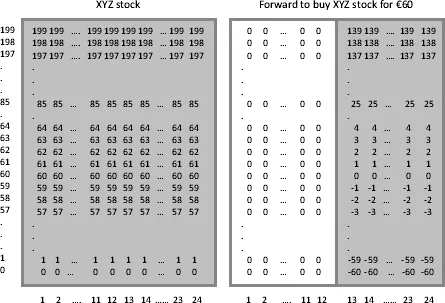

Let us apply the concept of state-contingent claims to known securities. Suppose you buy one share of XYZ SA stock currently trading at €45 per share and pays no dividends. You intend to hold the share for 2 years. To simplify things, we assume that the stock trades once a month and in increments of €1. The minimum price is €0 (a limited liability company cannot have a negative value) and the maximum price is €199. The share of XYZ SA can be viewed as a package of claims. Each claim represents a contingent cash flow from selling the share for a particular price in a particular month in the future. Only one of those claims will ever pay, say when we sell the stock for €78 in month 16. We can arrange the potential price levels from €0 to €199 in increments of €1 to have overall 200 possible price levels. We arrange the dates from today to 24 months from today (our holding horizon). The stock is equivalent to 200 times 24, or 480 claims. The easiest way to imagine this set of claims is as a rectangle with time on the horizontal axis and potential stock prices (states of nature) on the vertical axis. The price of the stock today is equal to the sum of the values of all the claims, i.e. all the state- and time-indexed squares of the rectangle.

Figure 1.1 shows the stock as a rectangle of 480 state-contingent claims. It also shows a forward contract on XYZ SA's stock viewed as a subset of this rectangle. Suppose we enter into a contract today to purchase the stock 13 months from today for €60. The forward can be viewed as a 200-by-24 rectangle with the first 12 months’ worth of claims taken out (equal to zero, as no action can be taken). If, in month 13, the stock trades above €60, we have a gain; if the stock trades below €60, we have a loss equal to the difference between the actual stock price and the precontracted forward price.

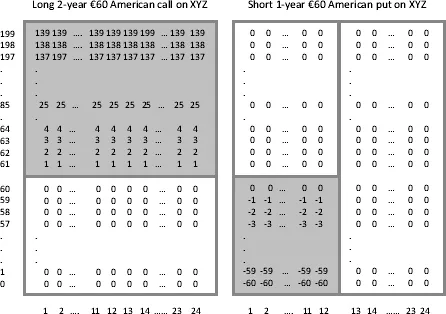

Figure 1.2 shows a long American call option contract to buy XYZ SA's shares for €60 with an expiry 2 years from today as a 139 × 24 subset of our original rectangle, the rest zeroed out. The squares corresponding to the stock prices of €60 or below are eliminated, because they have no value. The payoff of each claim is equal to the intrinsic (exercise) value of the call. Figure 1.2 also shows a short American put struck at €60 with an expiry in 12 months.

The fundamental tenet of the option valuation methodology which applies to all securities is that if we can value each claim (one square of the rectangle) or small sets of claims (sections of the rectangle) in the package, then we can value the package as a whole sum of its parts. Conversely, if we can value the package, then we are able to value subsets of claims through a subtraction of the whole minus a complement subset. Also, we may be able to combine disparate (dependent on different state variables) sets of claims (stocks on equity prices and bonds on interest rates) to form complex securities (a convertible bond). By subtracting one part (option) from the value of the combination (convertible bond), we can infer the value of a subset (straight bullet bond).

In general, the value of a contingent claim does not stay constant over time. If the holder of the life insurance becomes sick during the year and the likelihood of his death increases, then the value of all claims increases. In our stock example, the prices of the claims change as information about the company's earnings reaches the market. Not all the claims in the package have to change in value by the same amount, however. An improvement in the earnings may be only short term. The policyholder's likelihood of death may increase for the days immediately following his illness, but be less for more distant dates. As the prices of the individual claims fluctuate over time, so does the value of the entire bundle. However, at any given moment of time, the sum of the values of the claims must be equal to the value of the package, the insurance policy, or the stock. The valuation effort is restricted to here and now, and we have to repeat the exercise an instant later.

A good valuation model strives to make the claims in a package independent of each other. In our example, the payoff of the life insurance policy depends on the person dying during the month, not on whether the person is dead or alive. In that set-up, at most one claim of the whole set will pay. If we modeled the payoff to depend on being dead and not dying, all the claims after the morbid event would have positive prices and be contingent on each other. Sometimes, even with the best of efforts, it may be impossible to model the claims in a package as independent. If a payoff at a later date depends on whether the stock reached some level at an earlier date, the later claim's value depends on the prior one. A mortgage bond's payoff at a later date depends on whether the mortgage has not already prepaid. This is referred to as a survival or path-dependence problem. As our imaginary two-dimensional rectangles cannot handle path dependence; we ignore this dimension of risk throughout the book as it adds very little to our discussion and can usually be handled by models.

Let us turn to the definition of risk sharing.

Definition Risk sharing is a purchase or a sale, explicit or through a side contract, of all or some of the state-contingent claims in the package to another party.

In real life, risk sharing takes many forms. The owner of the XYZ share may decide to sell a covered call on the stock (see Chapter 5). If he sells a 2-year American call struck at €60, and gives the buyer the right to purchase the share at €60 from him even if XYZ trades higher in the market, the covered call seller is capping his stock-cum-option payoff at €60 in exchange for an up-front option premium that he receives. This corresponds to exchanging the squares corresponding to price levels above €60 for squares with a flat payoff of €60, or to subtracting, one-by-one, the payoffs in the American call package in Figure 1.2 from all the state-contingent claim payoffs in the stock package in Figure 1.1. This illustrates the important risk-sharing role of options in financial markets. Stockholders can buy or sell off parts of their holdings, and others can acquire subsets of the entire stock risk.

Another example of risk sharing is the hedge of a corporate bond with a risk-free government bond. A hedge is a sale of a package of state-contingent claims against a primary position, which eliminates all the risk of that position coming from one state variable. The sale of a security that is identical to the primary position is the only transaction that can eliminate all the risk. A hedge always leaves some risk unhedged! When a trader purchases a 10-year 5% coupon bond issued by XYZ Corp. and, in an effort to eliminate interest rate risk he simultaneously shorts a 10-year 4.5% coupon government bond – duration-matching the size of the short – he guarantees that for small parallel movements in the interest rates, the changes in the values of the two bonds are identical, but opposite in sign. If interest rates rise, the loss on the corporate bond holding will be offset by the gain on the short government bond. If interest rates decline, the gain on the corporate bond will be offset by the loss on the government bond. However, as explained in Chapters 2 and 7, the second state variable credit spread is completely unhedged. In fact, the trader speculates that the credit spread on the corporate bond declines. Irrespective of whether interest rates rise or fall, the trader gains if ever the XYZ credit spread declines since the corporate bond's price will go up more, or go down less, than that of the government bond. It is only when the credit standing of XYZ worsens and the spread rises, that the trader will suffer a loss. The corporate bond is exposed over time to two dimensions of risk: interest rates and corporate spread. In the state-contingent claim sense, the corporate bond would be represented by a large rectangular cube with time, interest rate, and credit spread as dimensions. The government bond hedge eliminates all potential payoffs along the interest rate axis, reducing the cube to a plane, with only time and credit spread as dimensions.

Almost any hedge or relative value arbitrage position discussed in this book can be thought of in the context of a multidimensional cube defined by time and risk state-variable axes. The hedge eliminates a dimension or a subspace from the cube.

1.3 TRANSACTIONAL STRUCTURE OF FINANCIAL MARKETS

Most people think of financial markets as a giant bazaar with individuals buying and selling stuff to each other for money. The “stuff” they trade is paper claims on future earnings, coupon interest, or insurance payouts. If you buy good claims and their value goes up, you can sell them for more; if you buy bad ones and their value goes down, you lose money.

Finance and economics professionals usually offer a seemingly more complete description of this process, adding detail about who buys and sells what and why in each market. They may educate us that businesses and governments need funds. They issue stock, lease- and asset-backed bonds, unsecured debentures, sell short-term commercial paper, or rely on bank loans. These issuers get their required capital and, in exchange, promise to pay interest payments or dividends in the future. The legal claims on business assets are purchased by investors, both individual and institutional, who spend cash today to get more cash tomorrow, i.e. they invest. Investors can leverage themselves by borrowing cash to buy more securities, and through that they themselves become issuers o...