![]()

Part I

The Nature of Desertification

![]()

Chapter 1

Desertification, Its Causes and Why It Matters

By definition, human induced land degradation, which is how desertification is defined, is caused by the actions of people that have a negative impact on the ‘functioning’ of the environment, as it is being eco-culturally experienced and as regards its value as a natural resource. A function is something like clean water, air and food but it can also have an aesthetic or cultural nature. Some functions can be restored and new ones created in landscapes that have become degraded with respect to their earlier state. Species and cultures differ in their capacity to survive the loss of their functions and habitat. This ‘resilience’ is reflected in how they are affected by land degradation and desertification. Resilience can be with respect to nature but also with respect to the economy and the social capital of people. Natural capital is provided by nature and it is the basis of all economic activity and human existence.

Sustainable land use and management are about establishing principles that can be brought into practice as a response to land degradation and desertification. In many cases land can have its quality and values restored and degradation can be put into reverse. Lost qualities or functions of the land can be restored through sustainable land management and with the help of natural processes. But in many cases changes are irreversible.

Parts II and III of this book include local and global level case studies. They describe key processes and attributes of landscapes relevant to desertification and give details of the actions that can be taken to ameliorate or adapt to it in different socio-environmental contexts. The cultural and economic pressures and drivers of land degradation are immense and much of the world is comprised of degraded landscapes. Because these are a consequence of our lifestyles, culture, attitudes and values they can be systematically changed by strategically planned human efforts. The situation is quite positive to the extent that the future does not have to be the consequence of actions that degrade the landscape; there can also be other actions that lead to restoration and the reversal of land degradation. The same socio-economic and financial forces that resulted in land degradation as a result of the critical values of natural processes being disregarded can be used to organize the responses that must be made.

This book introduces some of the fundamental principles and practices of land degradation and land and landscape management as they appear in 2011. It discusses the strategies, policies and actions that are being undertaken by different organizations responsible for land degradation and who are trying to deal with it. Successful strategies and approaches that can be used to reverse land degradation are well known and these are described.

The findings of European research on desertification were recently reviewed by an expert group for the European Community (Roxo 2009). Their intention was to raise awareness of the urgent state of land degradation in Europe and explain the current situation. It was also to show what Europe had achieved and what could still be done. As well as the severity and consequences of land degradation, the experts examined the main processes associated with it, such as soil and ecosystem degradation, erosion, salinization and wildfires; the causes such as climate change and land use practices, pollution, contamination and compaction; and the different landscapes in which land degradation is most concentrated.

More or less in parallel, an International Conference was organized by SCAPE (Imeson et al 2006) that brought together experts from environmental law (Hannam and de Boer 2002) and the land degradation communities. A little later, an International Forum on Soils and Society (2007) supported by the Iceland Government to celebrate 100 years' existence resulted in A Call for Action. One of the most common universal problems is that people appropriate natural resources or farm in an unsustainable way, irrespective of any law. The Brazilian Environmental Protection Agency cannot prevent the rain forest being used illegally as a source of fuel for pig iron production because it reduces the transport cost of iron ore on the way to China which generates billions of dollars each month. Or alternatively they are exempted.

The unanimous conclusion was that with the present scientific understanding, it is possible to evaluate the degree to which the actions and policies being used to address desertification are appropriate in view of scientific knowledge (Briassoulis 2010). This fortunate situation is an outcome of a large research effort in many countries and regions. There is sufficient scientific legitimacy to place land degradation at the top of the priority list of governments. This is equally true for other parts of the world, where similar knowledge and understanding has been acquired since concerns were raised at least two hundred years ago by Europeans observing the impact of land use in marginal areas in Europe but especially in South and North America.

A Holistic Systems Based Approach

When considering the nature and causes of desertification many different assumptions can be made that influence the methodology used to present what might seem to be an extremely complex environmental problem. The traditional approach is to evaluate the different factors ranging from matters such as geology, climate, economy and culture. It is difficult to be conclusive because it is hard to integrate and quantify factors that are always changing and uncertain.

A different way is to start holistically with just one system. Desertification can be conceptualized as if there is just one socio-economic system in which society finds itself with nature (for example, Huxley (1885), van der Leeuw (1998)). This way of looking at desertification was developed by several research schools in the 1990s at a time when ways of better integrating the physical and socio-economic factors affecting land degradation were being sought. In a single discipline approach it becomes clear that what is important are people's actions and what they do and the relationships between them. Addressing desertification is attainable if alternative positive cultural habits and practices are adopted since the things people do directly change the biophysical processes and alter the way in which the single system will respond.

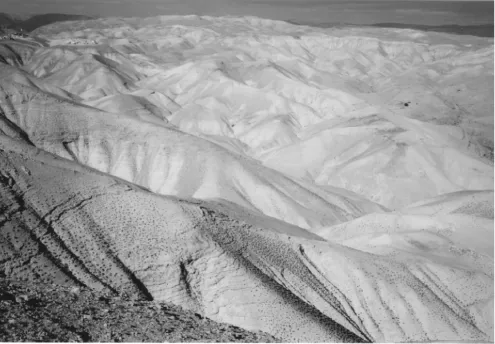

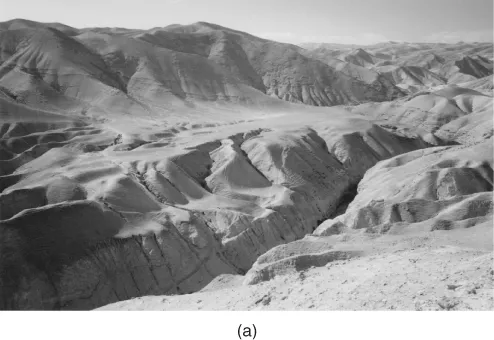

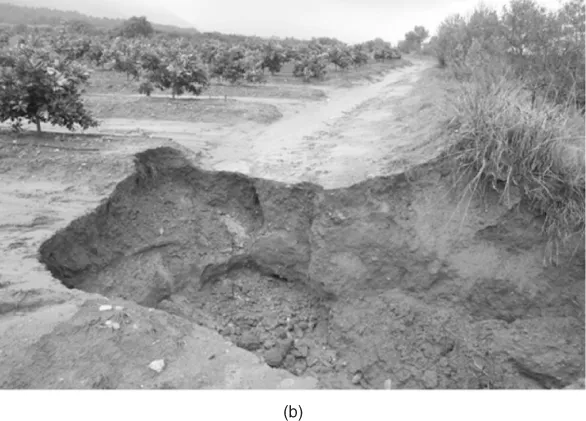

Man and nature are in fact acting at one scale symbiotically. Symbiosis describes the close and often long-term interactions between different biological species. Symbiotic relationships can be necessary for the survival of at least one of the organisms involved. Relationships, therefore, matter because all life has contributed to the present state of the earth. Earthworms, trees and fungi are no less significant than humans in influencing the properties of the single socio-environmental earth system. All human actions that affect other life are important because of symbiosis and interdependence. Although symbiosis has received less attention than other interactions such as predation or competition, it is an important selective force behind evolution. Desertification then is about deserts and drylands such as the Judean desert (Figure 1.1) which may or may not be experience current degradation. It is also about the spread of desert-like conditions or features (Figure 1.1) as a result of human actions (Figure 1.2) in Valencia, Spain.

1.1 The Nature of Desertification

1.1.1 Concern About Desertification in Developed Countries

Europe and America became concerned about desertification in the 1980s (Fantechi and Margaris 1986). It was postulated that desert-like conditions might spread to southern Europe from North Africa and to the south western United States from Mexico. There was similar evidence of such desertification in north east Brazil, China, Africa and India. According to Canadian meteorologist Hare (1976) who investigated this for the United Nations, it was not clear if this was the result of human causes or climate. In neither wealthy nor poor countries is there much evidence linking poverty to desertification. Poverty has very many causes and land degradation is linked to them in historical and political contexts that are about population growth, culture and exploitation of rural populations. Desertification and land degradation can be brought about by many different things such as conflict and migration, land use and farming, water use and soil contamination. It can also be brought about by the appropriation of people's natural resources and functions and these affect both developed and developing nations. Examples of strategies, policies and laws that address these are numerous (Arnalds 2005a and b).

Modern agriculture and forestry as well and the exploitation of natural resources involves using the land in ways that withholds and prevents it from doing what it once did in the way of regulating the hydrological cycle and energy balances, transformation processes and providing food chains and food webs.

It was confirmed by the EU working group on Desertification, set up by the European Soil Forum in 2005, that the higher the subsidies, the higher the land degradation because of the pressures and disruptions that these place on ecosystems. This is true everywhere because of the way subsidies affect human behaviour. The mathematics is explained in several monographs at the Santa Fe Institute, New Mexico. The main aims of forestry and agriculture are to provide resources and food and to sustain the economy and protect jobs. These are the strategic goals of the U.S. Forest Service, for example, whose main mission is focused on their employees' needs and the increased production of timber. In achieving these rational goals, the natural and cultural environments are ignored and often degraded of their other functions (protection from flooding) and capital (value of this protection) is lost. Actions and practices take place that should in fact be regulated because they cause harm to the life with which we share a symbiotic dependence. For most people, the land is real estate and a provider of food and raw materials. Society has not been effective in promoting values that make us conscious of being symbiotically part of nature. There is a limited or lack of any legal duty of care towards the environment, land and soil. There is the real possibility that the support functions of the earth are being compromised because of the disappearance of species...