- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Is the nano-age here to stay or will a bubble soon burst? This thought-provoking page-turner takes a critical glance at how nanotechnology has affected virtually all areas of our lives. From the pharmaceutical industry to energy production and storage, many fields have been truly revolutionized during the nano-age. The internationally renowned author explores the topic in nine entertaining chapters.

Information

1

Capturing Sun’s Energy

1.1 Solar Power: Now

Electricity is silent, clean, and easily transported and converted into work. Unsurprisingly, therefore, electric power is the most useful and desirable form of energy available to modern society. Yet, exactly like hydrogen, electricity is an energy vector and not an energy source. This means that we need to produce electric power by converting primary energy sources into electric power. At present, besides a 16% share from nuclear fission (www.world-nuclear.org), we produce electricity mainly by burning hydrocarbons and, sadly, much cheaper coal. For example, still, in 2006 nearly half (49%) of the 4.1 trillion kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity generated in the USA used coal as its energy source (www.eia.doe.gov).

Overall, presently, close to 80% of the energy supply worldwide is based on fossil fuels like coal, oil, and gas [1]. Over the next decade, China alone will need to add some 25 GW of new capacity each year to meet demand – equivalent to one large coal power station every week. Coal, unfortunately, contains mercury and, along with production of immense amounts of climate-altering CO2, its combustion is causing pollution of the oceans and of the food chain. To abate emissions and stop climate change, the biggest challenge of our epoch is to obtain electricity directly from the sun.

The conclusions of the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) analyses concerning the potential impact of various scenarios of CO2 emission trajectories (www.ipcc.ch) provide evidence that if the global average temperature increases beyond 2.5 –3.0°C serious, and likely irreversible, negative consequences to the environment will result, with a direct impact on agriculture, water resources, and human health [2]. In the absence of serious policies to reduce the magnitude of future climate changes, the globe is expected to warm by about 1–6 ° C during the twentyfirst century. The estimated carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration in 2100 will lie in the range 540–970 ppm (parts per million), which is sufficient to cause substantial increases in ocean acidity as well as irreversible modifications to climate and nature [3].

Clearly, to satisfy our growing energy needs (a predicted doubling of energy demand by mid-century and a tripling by the end of the century) [21] and resolve the world’s sustainability crisis, we urgently need to use a fraction of the immense solar energy amount that the Earth receives annually from the sun: 3.9 × 1024 joules, namely four orders of magnitudes larger than the world energy consumption in 2004 (4.7 × 1020 J), and enough to fulfill the yearly world demand of energy in less than an hour.

Realization of such a change will require a massive effort to discover and develop new technology solutions to capture vast amounts of dilute and intermittent, but essentially unlimited, solar energy to sustain our forecasted needs; and also to scale its conversion into high power densities and readily storable forms. The energy and societal challenge before us in developing CO2-neutral, solar energy differs in two ways from past large-scale challenges, namely, in:

1) the large magnitude and relatively short time scale of the transition;

2) the cost-competitive aspect of the transition.

Solutions will be achieved by exploiting advances in nanoscale science and technology. Revolutionary nanotechnology-enabled photovoltaic materials and devices are being developed to satisfy the world demand in sustainable electricity at a price level of less than $0.10 per kWh. Similarly, nanotechnology-based disruptive devices for electric energy storage, such as new batteries and capacitors, are required to enable massive deployment of solar power. Most importantly, this transformation must be accomplished in an economically and environmentally feasible manner in order to achieve a positive global impact. Hence, the cost of battery technologies must plummet from the current $1000per k Wh to a level approaching $10 per kWh to become cost competitive.

1.2 Never Trust the Skeptics

Exactly in the same way that the Internet was not invented by taxing the telegraph, so cheap and abundant electricity from the sun will not be obtained by adding taxation on carbon dioxide emissions, but rather by inventing new, affordable clean technologies [4]. Nanoscale science and technology will play a crucial role in reaching this aim.

Solar power currently provides only a very small fraction of global electric power generation, about 12 GW of installed capacity globally, as of 2009, but newly installed capacity is growing at approximately 30% per year and is accelerating. Concentrated solar power (CSP) has already been identified as a clean technology that can satisfy the world’s rapidly growing energy demand.1) Accordingly, investments are finally flowing and the first CSP plants, such as that in the Spain’s city of Seville (Figure 1.1) serving 6000 families, are starting operation.

Figure 1.1 The Solucar 11 MW solar thermal plant outside Seville, Spain, produces enough electricity to power 6000 homes. CSP is a large-scale technology capable of satisfying massive electricity demand. Photograph courtesy of the BBC; reproduced with permission.

In Europe, France’s President Sarkozy and Germany’s Chancellor Merkel seem to have understood the situation. In establishing the new Union for the Mediterranean (Figure 1.2) they and all other government leaders of the member States have agreed to explore feasibility of large-scale generation of solar electricity in North Africa to supply Europe and Middle East countries through solar thermal technologies. Meanwhile, the often invoked two billion citizens of developing countries lacking access to an electric grid will start to self-generate electricity for their basic needs using photovoltaic modules whose price has dropped from almost $100 perwatt in 1975 to $1.6perwatt at the beginning of 2009.

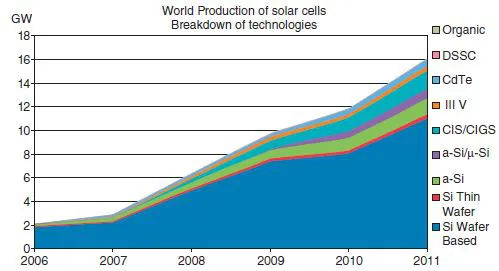

Direct conversion of the sun’s radiation into electricity, namely photovoltaic s (PV s), is being developed rapidly. After 40 years of losses and governmental subsidies, the $37 billion photovoltaics industry has turned into a profitable business, growing for the last decade at 30% per annum [5]. In this context, the installation of thin-film (TF) systems more than doubled last year and now accounts for some 12% of solar installations worldwide [2]; the revenue market share of TFPV was expected to rise to 20% of the total PV market by 2010 (Figure 1.3) [6]. Thin-film modules are less expensive to manufacture than traditional silicon-based panels and have considerably lowered the barrier to entry into the photovoltaic energy business. From the heavy, fragile silicon panels coated with glass the sector is thus rapidly switching to thin film technologies using several different photovoltaic semiconductors.

Figure 1.2 Established in 2008, the Union for the Mediterranean consists of 42 countries and has a major project: a Mediterranean Solar Plan to install concentrating solar power in the deserts and feed huge amounts of electricity to all member States, thereby ending energetic dependency on oil and natural gas. Reproduced from wikipedia.org, with permission.

Four years of high and increasing oil prices and the first ubiquitous signs of climate change have been enough to assist the market launch of several photovoltaic technologies based on thin films of photoactive material that had been left dormant in academic and industry laboratories for years. For example, in 2004 a leading manager in the PV industry, exploring the industry perspectives, concluded: “thin-film PV production costs are expected to reach $1 per watt in 2010, a cost that makes solar PV competitive with coal-fired electricity “[7].

Figure 1.3 The forecast for the photovoltaic market, with a breakdown per technology, points to an annual growth rate of 70% for TFPV from 2007 to 2010 Reproduced from yole.fr, with permission.

However, the first thin-film solar modules profitably generating electricity for $0.99 per watt (i.e., the price of coal-fired electricity) were commercialized in late 2008 by the US company First Solar.

Now, regarding the “feed-in “tariff schemes by which, initially, governments in countries like Germany and Spain and now Italy, France, and Greece aim to incentivize production of solar electricity, the “skeptical environmentalist “Bjørn Lomborg [8] (Figure 1.4) would probably tell you that this is just another example of the poor (through an extra tax on the electric bill) financing the rich (purchasing the solar modules). But Bjørn, in this case, would be wrong.

The governments of these countries established the incentives to develop a large and modern photovoltaic industry that, thanks to the large profits fueled by the incentives, could finance innovation and lower the price of solar electricity. How right they were! Indeed, a large body of new commercial PV technologies has emerged in the last five years and last month the US-based company First Solar announced a reduction in production costs to 1$W−1 (one dollar per watt), from 5$W−1 in 2005 when the company started production of its modules based on cadmium telluride (a readily available and non-toxic inorganic salt). Cumulative production planned for 2009 by this company alone is 1 GW, that is, the power similar to that generated by a new-generation large nuclear power plant.

Figure 1.4 “The poor financing the rich “would say the “skeptical environmentalist” Bjørn Lomborg commenting on the “feed-in tariff” scheme adopted by Germany (and many other states). But Bj ørn, in this case, would be wrong. Photograph by Emil Jupin, reproduced from lomborg. com, with permission.

In management, as in politics, never trust the skeptics too much!

1.3 Solar Power for the Masses

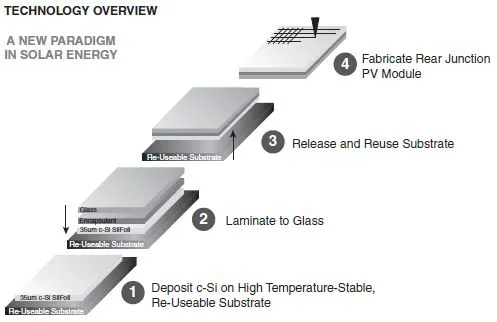

So-called “thin film “photovoltaics are opening the route to low cost electricity. In this context, thin films are 100nm–100μ m thick and made of organic, inorganic, and organic –inorganic solar cells deposited over rigid or flexible substrates by high-throughput (printing) technologies. If, for example, 35μ m of silicon were used to manufacture a solar cell instead of the state of the art 300mm-such as in the case of the SilFoil technology based on large area, multi-crystalline silicon foils developed by NanoGram (www.nanogram.com) (Figure 1.5)–the cost of silicon-based solar modules would be below $1 W −1.

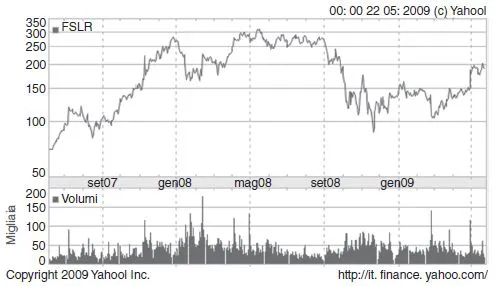

While similar small start-ups eagerly compete to introduce new solar technologies, First Solar already manufactures the equivalent of one large nuclear power station, using a deposition technique of inorganic nanocrystals of cadmium telluride. Floated on the New York Stock Exchange (NASDAQ) in November 2006 the company’s stock price rapidly recovered from the financial turmoil due to the 2008 financial crisis (Figure 1.6) as production–and sales–increased 100-fold and the company has become the world’s second largest in the photovoltaic business.

Figure 1.5 Nanogram plans to start production of its SilFoil modules in 2010 in a US-based production facility; 5 MW of capacity on ultra-thin crystalline silicon, which it says will reduce the cost of silicon-based solar cells to below $1 per watt by an innovative technology based on large area, multi-crystalline silicon foils. Reproduced from nanogram.com, with permission.

The above is due to technical control of the deposition process using a technique called chemical vapor deposition. Without such control, such a disruptive technology would not be on the market. It is disruptive because, in the face of the new threat posed by this highly competitive technology, manufacturers of traditional silicon solar panels reacted by ramping production, aiming to reduce cost by economies of scale. This, in its turn, led to oversupply of polysilicon (the raw material for Si-based solar cells) from silicon manufacturers.2) The overall result is that, in early 2009, solar modules in Europe and in the rest of the world were selling at 1.7 € W−1. Solar energy for the masses is now a reality!

Figure 1.6 Price of First Solar stock, 2007–2009 (as of May 2009). Reproduced from google.com, with permission.

At present, most existing production tools in the solar industry have a 10–30 megawatt (MW) annual production capacity. A single machine with a gigawatt throughput would be highly desirable, leading to far higher returns on the capital invested. In late 2008, thus, Nanosolar opened a factory in California that can produce 430 MW of solar capacity a year, nearly the size of an average coal-fired power plant, by simply printing a nanoparticle ink. More precisely, the company manufactures thin film copper-indium-gallium-selenide (CIGS) solar cells by printing the active CIGS material onto mile-long rolls of thin aluminum foil (Figure 1.7), which is later cut into solar panels.

The new ink (Figure 1.8) is made of a homogeneous mix of CIGS nanoparticles stabilized by an organic dispersion. Chemical stability ensures that the atomic ratios of the four elements are retained when the ink is printed, even across large areas of deposition. This is crucial for delivering a semiconductor of high electronic quality and is in contrast to vacuum deposition processes where, due to the four-element nature of CIGS, one effectively has to “atomically” synchronize various materials sources.

Printing is a simple, fast, and robust coating process that further lowers manufacturin...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title

- Series

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Preface

- About the Author

- 1: Capturing Sun’s Energy

- 2: From Chemistry to Nanochemistry

- 3: Storing and Supplying Clean Energy

- 4: Catalysis: Greening the Pharma Industry

- 5: Organically Doped Metals

- 6: Protecting Our Goods and Conserving Energy

- 7: Better Medicine Through Nanochemistry

- 8: Getting There Cleanly

- 9: Managing (Nano)innovation

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Nano-Age by Mario Pagliaro in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Nanotechnology & MEMS. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.