- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Museums and the Public Sphere

About this book

Museums and the Public Sphere investigates the role of museums around the world as sites of democratic public space.

- Explores the role of museums around the world as sites of public discourse and democracy

- Examines the changing idea of the museum in relation to other public sites and spaces, including community cultural centers, public halls and the internet

- Offers a sophisticated portrait of the public, and how it is realized, invoked, and understood in the museum context

- Offers relevant case studies and discussions of how museums can engage with their publics' in more complex, productive ways

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

The Public Sphere

The term “public” is pivotal in the museum context. As suggested in the introduction, the multiple applications and pervasive use of the term may appear – misleadingly – to render it useless. I examine in this chapter the complexity of the term in order to reveal both its shortcomings and its potential in the context of museums. I also explore possible ways to extend its use in that context.

Apart from the general everyday references to the museum’s public nature or function, the most frequently cited reference to the term “public” in museum studies is to the work of Jürgen Habermas (1989). There is a certain irony here, as I detail later, in that Habermas does not himself make the link between culture, spatial practices or aesthetics often assumed in such citations. But inaccuracies in the ways in which Habermas’s work is employed in discussions about museums are less important than an understanding of how his work may lend itself to a deeper exploration of museums, in particular of the way in which they attempt to be democratic and genuine institutions of, and for, the public. In this sense, I rework Habermas’s “public sphere” as a cultural public sphere to reveal the significance of “the cultural” in understanding the public realm. I will begin with a detailed consideration of the key tenets of the idea of the “public sphere,” and then work towards an understanding of how museums are relevant to the concept.

The notion of a “bourgeois public sphere” was proposed by Jürgen Habermas in 1962. The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere (STPS) was translated from German in 1989 and has received considerable attention from critics since. There has been a resurgence of interest in critical theories of the public sphere, particularly theories that have emerged from the Frankfurt School – from Habermas, Oskar Negt and Alexander Kluge (Koivisto and Valiverronen, 1996; Johnson, 2006). These critical theorists, as we see later in this chapter, have refocused the attention of academics in the Western world on the political implications of the public sphere, because of the way the concept of the public sphere engages with concepts of democracy and societal organization (Johnson, 2006).

Habermas identified literary discourses of the bourgeois public as most prevalent and influential in his historical model and theory. (This may be because of his background in journalism.) I suggest this is a relatively narrow conception, in which the literary discourse and literary “publics” are prioritized at the expense of other “publics.” Those that challenge Habermas’s model or are not included in his concept may, however, be understood by investigating cultural discourses other than literary ones. The significance of cultural disciplines is not sufficiently apparent to Habermas. Though he claims that interdisciplinarity is necessary for considering the public sphere and discourses on democracy, Habermas himself fails, importantly, to draw on those disciplines that are concerned with cultural institutions and practices in civil society and democracy.

The idea of the “public,” as defended in this book, intersects with notions of “public” in several academic disciplines and related professions. We find, however, a number of poorly conceived understandings of the public sphere in these other disciplines, particularly in understanding the intersection between museums and museum studies, and history, colonialism, urbanism, and visuality. A new, cultural understanding of the public sphere acknowledges many different ways of “being in public.” The public is not an amorphous or homogenous grouping of subgroups or individuals. Nor is public space merely a simple nostalgic representation of the public sphere (see Chapter Three). The production of the public sphere involves complex exchanges and negotiations between different forms of communications and practices of being in public. This is not a notion that rests upon difference, bracketed off from an otherwise all- inclusive idea of the public. I will suggest that, from a perspective that is cultural, spatial, and intersectional, it is also possible to identify the emergence of new publics.

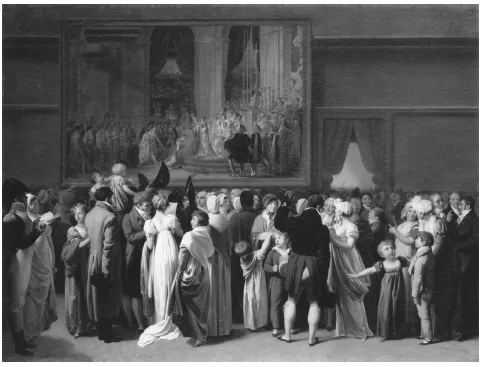

Many critical accounts of the term “public” investigate specific or actual sites in their search for evidence of the existence of a public sphere (Iveson, 2008; Mitchell, 2003; Smith and Low, 2007). However, these actual sites are often given marginal status in critical accounts of the public sphere, as such. This is despite the potential centrality of visual and spatial discourses to various formations and understandings of the public sphere. It is essential to consider these discourses (and their limitations) as iterations, as practices, of public address and potentially representative discourses of the public sphere. The performative aspect of democratic sites is often overlooked, while the existence of physical space is prioritized over the practice of democracy. The practice of being part of the public in the space of the museum – recognizing how being a citizen in the museum constitutes the public – is valuable for understanding the democratic nature of the museum. To understand democracy we also need to recognize that many different versions of democracy exist. There are, however, some key or core characteristics, including a particular form of rhetoric (see Held, 1996). By investigating actual spaces and places of the public in which this rhetoric is performed, it is possible to see how public spaces constitute a critical visual discourse of the public sphere. These spaces include the museum.

Image 1.1 Louis-Léopold Boilly, The Public in the Salon of the Louvre, Viewing the Painting of the “Sacre” begun 1808, Woodner Collection. Image courtesy of the Board of Trustees, National Gallery of Art, Washington, USA

Habermas and the Public Sphere

The idea of the public sphere has received renewed critical attention since the translation of Habermas’s foundational text, The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere, coincided with major world events including the fall of the Berlin Wall, the reunification of Germany, and the Tiananmen Square Massacre in China (Koivisto and Valiverronen, 1996). The work of Jürgen Habermas, a critical theorist, member of the Frankfurt School and foremost commentator on the public sphere, is also considered valuable because of its strengths relative to other theoretical approaches. Benhabib (1992a), for example, proposed three distinct models of the public sphere, and favored Habermas’s over the Arendtian and liberal (Kantian) conceptions, because “questions of democratic legitimacy in advanced capitalist societies are central to it.” “Nevertheless,” she added, “whether this model is resourceful enough to help us think through the transformation of politics in our kinds of societies is an open question” (Benhabib, 1992a: 74). A discussion of the relevance of Habermas’s theory to the museum will provide one point of entry to answering this question.

Habermas’s work has received significant critical responses from many disciplines (including sociology, philosophy, media studies and cultural studies). Of particular interest in this present discussion is how his work and that ofhis critics intersect with space and vision, or with the spatial and visual discourses of the public sphere.

In Habermas’s STPS, the argument about the central role of discourse on public matters in the formation ofthe public sphere became in particular the basis of his later work on “communicative action.” 1

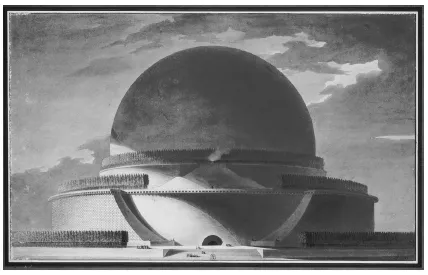

Habermas repeatedly uses the term “public sphere” but does not elaborate on its spatiality in either a material or theoretical sense. Despite this, the notion of a public sphere invokes certain spatial metaphors, the most obvious being a spherical form, such as a globe or a ball. Specific forms of architectural space have historically represented political and cultural concerns in social or public life. For example, in Western cultures, the sphere, seen in Étienne-Louis Boullée’s 1784 project for a memorial to Isaac Newton (see Image 1.2, Cénotaphe de Newton) and in his museum and library designs, has been purposely used historically to represent democratic space in its “natural” form (Boullée, n.d.). The significance of such cultural forms and expressions of public space is, as we will see, overlooked in Habermas’s writing, and yet his concept of the public sphere both suggests and ultimately depends on spatiality.

The public sphere is not represented as an actual space in Habermas’s theory; instead, it refers to the conduct of public discourse, understood primarily as literary and discursive. It may therefore be found on the pages of an eighteenth-century pamphlet or in discourse about public matters in coffee houses, market places or literary salons. While Habermas’s historical model cites places where such discussion occurs (European coffee houses or market places, among others), the centrality of actual space for the public sphere is not, in itself, considered significant. This is examined later in Chapter Three.

Image 1.2 Étienne-Louis Boullée, Cénotaphe de Newton, 1784. Bibliothèque nationale de France

Habermas’s research into the emergence of the liberal bourgeois public sphere in eighteenth-century France led to the theory of the bourgeois public sphere as a “site” where the interests of the state, the commercial class and the bourgeoisie intersect. This model then became generalizable for Habermas as the “liberal public sphere” or “public sphere.” The public sphere exists between the state and the private body of persons; it functions to rationally contemplate matters of public importance. Habermas’s public sphere is not an “actual” body of people; yet it has the potential to have “real” power. The mechanism by which it becomes real is discourse or debate about matters of public importance. In this model these debates affect public opinion and have influence on government policy and its implementation. The spatial context itself is, Habermas implies, not relevant to, or constitutive of, such discussion.

To speak simply of influence is insufficient for understanding what is at stake. Nancy Fraser (1992: 134) distinguishes between “strong” and “weak” publics and argues that the public sphere – as a sphere between government and civil society – is weak because those “whose deliberative practice consists exclusively in opinion formation and does not encompass decision making” cannot claim to have real influence. For Fraser, deliberative practices do not necessarily translate into actual social change. The capacity to influence and the power to implement actual change is essential, she concludes. This requires a reworking of Habermas’s model to take into account the real-life processes of democracy. Fraser’s critique offers a model for subjecting Habermas’s theory to an analysis built around the centrality of cultural space. Indeed, if we consider Fraser’s argument in the museum context, we see that the capacity of the museum to exist between government and civil society is in many countries compromised by the state’s interest (via funding and policy) in the role and function of the museum. The museum’s capacity to be democratic, in Fraser’s sense, may be limited to opinion formation but not actual decision making and may not actually effect social change: in this manner the museum is rendered a “weak public.” As we will see, however, the capacity of the museum as a public sphere is more complex than this. It may be weak in its relationship with the state, but powerful in serving as a site for community and democratic “publics.”

Habermas’s concept of the public sphere remains valuable, however, despite inconsistencies in his use ofthe concept. Where he is clear, though, is in identifying literary discourses as media where the primary articulation of – and the formation of – the public sphere occurred: “The medium of this political confrontation was peculiar and without historical precedent: people’s public use of their reason (öffentliches Rosonnement)” (1989: 27). He continues:

The “town” was the life center of civil society not only economically; in cultural-political contrast to the court, it designated especially an early public sphere in the world of letters whose institutions were the coffee houses, the salons, and the Tischgesellschaften (table societies). (Habermas, 1989: 30)

He defines “public spaces” as sites where public discourse occurs. “The commons was public, publica: for common use there was public access to the fountain and market – loci communes, loci publica” (Habermas, 1989: 6). (Today this would also include print and electronic media with the actual physical space being secondary to the function of discourse on public matters.) Thus, while he emphasizes the “virtual” nature of the public sphere, concealed in the processes and exchanges of discourse, debate and communication, he also notes the physical spaces in which these processes took place. He fails, nonetheless, to recognize the significance of these spaces. The importance of this recognition, however, should not be overlooked. It will be ofsignificance in understanding the nature ofthe cultural and spatial public sphere.

For Habermas, the public sphere becomes known through the process of promotion and publicity generated by an emerging bourgeois public involved in reading societies and lending libraries, talking in coffee houses and clubs, seeking new ways to participate in the governance of their society. Habermas elaborates on the structured way in which the bourgeois public sphere developed into another platform from which the public could represent itself: “through the vehicle of public opinion it put the state in touch with the needs of society” (1989: 31). Publications and the development of the mass media became (and remain) critical conduits for such publicity. Publicity in Habermas’s work refers to the way in which the public sphere is disseminated: through the “world of letters,” where “rational critical debate which originated in the … conjugal family, by communicating with itself, attained clarity about itself” (1989: 51). The public articulation of arguments, presented in written form in letters, books and papers, became for Habermas a technical and cultural context in which the bourgeois public sphere was constituted (Warner, 1992).

Access to the public sphere of representation came to be considered a basic right of citizens, but for Habermas, representation in the public realm was conditional upon the public use of reason. 2 Sentiment, for Habermas, is too personal, irrational and particular in this model, and becomes a significant point of contention in critiques of the STPS. Relying on the “natural” goodwill of citizens will not guarantee, Habermas concludes, that the private interests of individuals will not determine their deliberation on public matters. To participate in public discussion citizens had to be willing to compromise, to transform their views. According to Habermas, then, new problems arose historically, as different sectors of society demanded access to the public sphere as a “basic right,” without necessarily understanding the rational form of discussion that was required for democracy to work.

The will to participate in democratic processes was not itselfsufficient for democracy to work. In the practices of Habermas’s public sphere in the late eighteenth century, citizens were required to participate, and comply with, recognizable forms ofinteraction in the public sphere, where the notion of freedom (of speech, of the press) was indeed limited, and contingent upon public norms that were subject to change. The mode of discourse allowed negotiation, hence change, to occur ifthere was consensus. To understand these basic rights and forms ofrepresentation, citizens needed to be literate in the structure of public discourse and democracy. Habermas’s concept of the bourgeois public sphere relied on the ability of citizens to recognize particular norms and forms of representations in the public sphere, namely the literary and the print media.

Habermas’s claims about the necessity and universality of “rationality” have been subject to criticism (Young, 1990, 1992; Robbins, 1993; Ingram, 1994; White, 1995). Inclusion in the public sphere, in Habermas’s model, requires reasoned and rational discourse on matters of public concern. Inclusion, however, does not ensure equality. Despite the rhetoric of inclusivity, a public sphere based on these principles, I argue, will be precarious. “Oppositional” public spheres, according to Habermas, should modify their forms of discourse to comply with apparent normative conditions of the “mainstream” public sphere. I argue, however, that this modification does not acknowledge the contested nature of the public sphere itself. The representation as well as recognition ofthe public sphere in spatial and visual discourses illustrates contestation ofthe public sphere. It serves to underline the relationship of the public to democratic forms, which are themselves based on contestation.

Despite such shortcomings in Habermas’s idea of the public sphere, Nancy Fraser concedes that “[t]he idea of ‘the public sphere’ in Habermas’s sense is a conceptual resource that can help overcome … problems arising from ‘less precise’ understandings and uses of the term” (1992: 110). For Fraser, “Habermas’s idea of the public sphere is indispensable to critical theory and democratic social practice” because it illustrates the “distinctions among state apparatuses, economic markets, and democratic associations,” which are central to democratic theory (1992: 111). This is useful for an understanding of the public role of the museum.

Richard Sennett (1992) has also written extensively on the history of the term “public” and its uses. According to Sennett, the practice of public life has shifted from an extrinsic to a more intrinsic individualistic practice. This, he argues, is to the detriment of both the individual and society. Sennett claims that confusion and difficulty can arise with the term “public” when individuals work out “in terms of personal feelings public matters that can be dealt with only through codes of impersonal meaning” (1992: 5). The individual, for Sennett, can act or engage on the public stage with the “greater” social good in mind, demonstrating a public conscience. This is distinct from self-gain. Sennett further argues that a problem emerges when notions of democracy are negotiated on an individualistic basis, because it is likely that such notions are being negotiated to satisfy individual needs rather than for the “common public good.” Yet what does it mean for something to be a “common” good? The use of the term “public” often “betrays a multiplicity of concurrent meanings” (Habermas, 1989:1). Such multiplicity is apparent in the museum context too.

Reasoned and rational discussion, according to both Habermas and Sennett, performs a normalizing function. It allows individuals to enter the public sphere as equals to negotiate public matters for the public good. However, while reason and rationality appear to be enabling in Habermas’s and Sennett’s models, they are also used to exclude individuals from the public sphere. Habermas’s model also excludes the dynamic way in which contestation between competing publics about what constitutes the public sphere may be an effective way for the public sphere to remain relevant in social life. It is Habermas’s requirement for reason and rationality that obscures these dynamics, and attracts most criticism from critics (and critical supporters alike). Both Habermas and Sennett recognize, however, that though rationality and reason are key principles of modern liberal democracy and the public sphere, they are not necessarily always employed. Nor are they used in the same way all the time. We consider this further, below.

The different types of public spheres that arise from this discussion of the bourgeois public sphere and the way in which the term “public” functions in relation to democracy are discussed below. The tensions between the empirical (historical) and abstract (theoretical) modes in the STPS must also be considered. To explore these tensions, I draw on Habermas’s critics, for whom the public sphere is exclusionary, and expand on their work to consider the importance of visual and spatial discourses. For museums, this discussion reflects tensions in theory and in practice. This is in part because the invention ofthe modern public museum coincides with the era in which Habermas locates his concept of the public sphere. In order to make this connection between Habermas’s public sphere and its visual and spatial aspects, let us turn to the STPS in detail.

Structural transformation of the public sphere

Emerging from the German intellectual tradition of critical theory, Habermas, like his colleagues in the Frankfurt School, was concerned with the theory and practice of democratic social systems. The Frankfurt School did not produce a unified critical theory of society, but engaged in extensive multidisciplinary approaches, and at times oppositional theoretical approaches to critical theory. It influenced many academic disciplines concerned with issues of social life and domination. The concept of the public sphere is said to be one of the most “significant contributions of the Critical Theory of the Frankfurt School” in recent decades (Koivisto and Valiverronen, 1996: 18).

In his preface to the STPS, Habermas states that “the category ‘public sphere’ must be investigated within the broad field formerly reflected in the perspective of the traditional science of ‘politics’” and argues that...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Dedication

- Title page

- Copyright

- List of Images

- Introduction

- 1: The Public Sphere

- 2: Historical Discourses of the Museum

- 3: The Museum as Public Space

- 4: Audience, Community, and Public

- 5: The Museum as Public Intellectual

- Conclusion

- References

- Acknowledgments

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Museums and the Public Sphere by Jennifer Barrett in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Museum Administration. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.