![]()

Part One

The Physiology of Metabolic Tissues Under Normal and Disease States

![]()

Chapter 1

Gut as an Endocrine Organ: the Role of Nutrient Sensing in Energy Metabolism

Minghan Wang

Department of Metabolic Disorders, Amgen, Inc., Thousand Oaks, CA, USA

Introduction

Energy homeostasis is balanced by food intake and energy expenditure. Both events are controlled by complex sets of neuronal and hormonal actions. Food intake is driven by a central feeding drive, namely, the appetite, which is induced under the fasting state after energy consumption through physical activities. Following food digestion, the passage of nutrients through the gastrointestinal (GI) tract generates signals that produce sensations of fullness and satiation. In particular, nutrients interact with receptors in the small intestine and stimulate the release of peptide hormones, the actions of which mediate physiological adaptations in response to energy intake. The commonly known GI peptides include the incretins, glucagon-like peptide 1 (GLP-1) and glucose-dependent insulinotropic polypeptide or gastric inhibitory peptide (GIP), as well as peptide tyrosine tyrosine (PYY), cholecystokinin (CCK), and oxyntomodulin. These peptide hormones are secreted from different regions of the small intestine. GLP-1, oxyntomodulin, and PYY are secreted from endocrine L cells that are mainly distributed in the distal small intestine (1, 2), whereas GIP is secreted from endocrine K cells primarily localized in the duodenum (3, 4). CCK is secreted from I cells in the duodenum (5). Nutrients released through the digestive tract induce secretion of GI peptide hormones, which subsequently bind to their respective receptors and trigger a cascade of physiological events. These receptors are expressed in tissues such as the central nervous system (CNS), the GI tract, and pancreas, and upon activation lead to suppression of appetite, reduced gastric emptying, and assimilation of nutrients. Nutrients can also suppress the secretion of GI peptides. For example, ghrelin, a peptide hormone released by the stomach under the fasting state that stimulates food intake (6), is suppressed after food ingestion (6).

GI peptides mediate two principal physiological events: (i) the feedback response on the CNS and the stomach to reduce food intake and slow gastric emptying, and (ii) the feedforward response, mediated particularly by the incretins, to prepare tissues for nutrient integration. In this regard, the small intestine is not only an organ for nutrient absorption but also a major site for providing hormonal regulation of energy intake and storage. GLP-1 and GIP are called incretins because they act on the pancreatic β-cells to increase insulin secretion at normal or elevated glucose levels. They also regulate glucagon secretion by pancreatic α-cells. These actions represent a critical step in preparing the body to switch from the fasting state to postprandial activities. By suppressing glucagon secretion, GLP-1 shut down hepatic gluconeogenesis and adipose lipolysis, two key biological pathways in maintaining energy homeostasis under the fasting state. In addition, GLP-1 can act directly on liver and muscle to regulate glucose metabolism independent of its incretin action (7). In the meantime, induction of insulin secretion by the incretins facilitates glucose uptake by the peripheral tissues. GLP-1 is also involved in the feedback response by acting on the CNS to suppress food intake. PYY and CCK exhibit a similar effect in the CNS underscoring the complexity of appetite regulation.

The magnitude and potency of the feedback and feedforward responses depend on both the nutrient content and the length of small intestine exposed. Although both glucose and free fatty acids (FFAs) modulate the secretion of GI peptides, their actions are mediated by distinct mechanisms because they have different residence times in the small intestine and interact with different nutrient-sensing receptors. In fact, even the activity of FFAs varies with their chain length. Moreover, the intestinal length exposed to nutrients and the nutrient contact sites are important determinants in GI peptide secretion.

Food Intake and Nutrient-Sensing Systems in the GI Tract

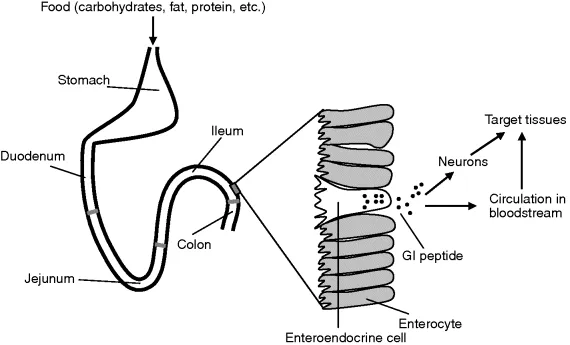

After ingestion, food chime is mixed with digestive juices in the stomach and propelled into the small intestine. The three segments of the small intestine, the duodenum, the jejunum, and the ileum, perform different digestive functions (Figure 1.1). Nutrients are generated from the digestion of carbohydrates, fat, protein, and other food components. The passage of nutrients through the small intestine not only facilitates absorption but also plays a role in regulating gastric emptying and satiety. The interaction of nutrients with the small intestine segments generates signals that regulate the rate of gastric emptying and food intake. The nutrient-sensing system consists of receptors, channels, and transporters in the open-type cells on the small intestine luminal surface. It responds to macronutrients and activates signaling pathways leading to the release of GI peptides, which subsequently act on the stomach and the CNS to slow gastric emptying and suppress appetite, respectively (Figure 1.1). In addition, some peptides such as the incretins stimulate insulin secretion and regulate glucagon secretion to help integrate nutrients into tissues post absorption (Figure 1.1).

Studies in pigs demonstrated that rapid injection of glucose into the duodenum during or immediately prior to feeding suppressed food intake (8, 9). The reduction in food intake far exceeded the energy content of the infused glucose (8, 9), suggesting that the effect of glucose on food intake is likely to be mediated by signaling events. In the meantime, hepatic portal or jugular infusion of glucose in pigs did not alter short-term food intake (10). These data suggest that the regulatory effect of glucose on food intake is a preabsorptive event and the sites of regulation are in the GI tract. To further understand the mechanisms by which dietary carbohydrates regulate energy intake, glucose was infused into the stomach or different segments of the small intestine in pigs. The infusion started 30 min prior to the meal and continued until the pigs stopped eating (11). It was found that infusion of glucose into the stomach, duodenum, jejunum, or ileum each suppressed food intake (11). But comparatively, jejunal infusion caused more reduction in food intake than elsewhere (11). These data suggest that glucose may interact with receptors or other sensing components expressed in various parts of the small intestine to control short-term energy intake. In addition to glucose, FFAs released from fat digestion also play important albeit more complex roles in controlling energy intake. Healthy human volunteers receiving ileal infusion of lipids consumed a smaller amount of food and energy and had delayed gastric emptying (12). Ileal lipid infusion also accelerated the sensation of fullness during a meal (12). However, intravenous (i.v.) infusion of lipids did not affect food intake (12), suggesting that lipids may interact with ileal receptors to induce satiety and reduce food consumption. Further studies suggest that digestion is a prerequisite for the inhibitory effect of fat on gastric emptying and energy intake. For example, administration of a lipase inhibitor increased food intake in healthy subjects or type 2 diabetic patients receiving a high-fat meal (13, 14), suggesting that FFAs, the breakdown products of fat after ingestion, rather than triglycerides, are the active nutrients that exert the regulatory effects. Likewise, sugars from carbohydrate digestion, rather than carbohydrates themselves, are the active nutrients that induce intestinal signals. Although both glucose and FFAs can stimulate a set of GI peptides that regulate appetite, gastric emptying, and insulin and glucagon release, they have differential effects. For example, glucose stimulates robust secretion of both GLP-1 and GIP, whereas FFAs from a fat meal elicit only modest GLP-1 secretion despite equally robust GIP secretion (15). Further, not all FFAs are equally active since the stimulatory effect depends on their chain length. Although FFAs with a chain length of greater than C12 stimulate CCK release, further increase in chain length has no additional effect, and C11 or shorter FFAs are not active (16, 17).

Like carbohydrate and fat meals, protein meals also activate the nutrient-sensing system but in different ways. In healthy human subjects, plasma GIP levels were elevated after both carbohydrate and fat meals but not a protein meal (15). However, intraduodenal amino acid perfusion in human subjects stimulated both GIP and insulin secretion (18, 19). Oral ingestion of mixed amino acids by healthy volunteers also increased plasma GLP-1 levels (20). These findings suggest that amino acids can function as nutrient-sensing agents, and a protein meal is likely to contribute to nutrient sensing in the GI tract. However, since mixed amino acids are not equivalent to a digested protein meal, GLP-1 secretion was studied in humans following a protein meal (15). A transient peak was observed at 30 min followed by a steady-state rise throughout the rest of the 3 h study period (15). The nutrients from the protein meal that stimulated GLP-1 secretion were a mixture of protein hydrolysates but not amino acids per se. It is important to carry out studies with protein hydrolysates that mimic the digested products in the GI tract. A protein hydrolysate (peptone) containing 31% free amino acids and 69% peptides induced the secretion of PYY and GLP-1 in the portal effluent of isolated vascularly perfused rat ileum after luminal administration (21). Peptones also induced CCK secretion and transcription in STC-1 cells, an established L cell line (22, 23). Peptones made from both albumin egg hydrolysate and meat hydrolysate stimulated the transcriptional expression of the proglucagon gene encoding GLP-1 in two L cell lines but not pancreatic glucagon-producing cell lines (24), suggesting that the signaling pathways mediating this effect are L cell/small intestine specific. In STC-1 cells, the proglucagon promoter contains elements responsive to peptones (25). In contrast, the mixture of free amino acids is at best a weak stimulant (21, 24). These data suggest that free amino acids may have a limited role in protein meal-stimulated GLP-1 or PYY secretion. However, amino acids are indeed involved in nutrient sensing in the GI tract. Aromatic amino acids may play a role in gastrin secretion because they activate the calcium-sensing receptor (CaR) on gastrin-secreting antral cells (26, 27). In addition, amino acids also stimulate CCK release (28, 29) and gastric acid secretion (30).

In addition to glucose, FFAs, amino acids, and digested peptides from proteins, other nutrients are also involved in the regulation of GI peptide secretion (21). At physiological concentrations, bile acids stimulate the secretion of PYY, GLP-1, and neurotensin (NT) (21). Interestingly, the threshold concentration of taurocholate for PYY and G...