- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Single Event Effects in Aerospace

About this book

This book introduces the basic concepts necessary to understand Single Event phenomena which could cause random performance errors and catastrophic failures to electronics devices. As miniaturization of electronics components advances, electronics components are more susceptible in the radiation environment. The book includes a discussion of the radiation environments in space and in the atmosphere, radiation rate prediction depending on the orbit to allow electronics engineers to design and select radiation tolerant components and systems, and single event prediction.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Edition

1Chapter 1

Introduction

1.1 Background

In recent years the dominant radiation effect in space-borne electronic systems has become the family of single event effects (SEEs). SEEs arise through the action of a single ionizing particle as it penetrates sensitive nodes within electronic devices. Single events can lead to seemingly randomly appearing glitches in electronic systems— frustrating errors that may cause anything from annoying (at best) system responses to catastrophic (at worst) system failures. The problem is particularly insidious due to the combination of its random nature, the omnipresent spectrum of high energy particles in space, and the increasing sensitivity of devices to SEEs as miniaturization progresses.

A SEE is a phenomenon that follows from the continuing trend in electronic device design toward higher density devices with smaller feature sizes. This trend permits faster processing of information with smaller required quantities of electric charge. As the charge involved has decreased, it has entered the region where corresponding amounts of charge can be generated in the semiconductor by the passage of cosmic rays or alpha particles. This charge can look like a legitimate signal, temporarily changing memory contents or commands in an instruction stream.

The single event upset (SEU) phenomenon was first suggested in 1962 by Walkmark [1962] and first reported in an operating satellite system in 1975 by Binder, Smith, and Holman [1975]. Both of these reports were generally ignored as they suggested responses well out of the mainstream of radiation effect studies of the time. However, in 1978, May and Wood [1979] reported alpha particle upsets in dynamic RAMs and Pickel and Blandford [1978] analyzed upsets in RAM circuits in space due to heavy ion cosmic rays. It was in this time period that IBM started major on-again off-again programs with alpha emitters and terrestrial cosmic rays [1979, 1981, 1996, and 2004]. In 1979 Guenzer, Wolicki, and Allas [1979], and Wyatt, McNulty, and co-workers [1979] experimentally observed upsets due to high energy protons such as those present in the Earth's trapped proton belts. Gradually, as more and more upset related problems have been observed in spacecraft, SEU has come to be recognized as a very serious threat to system operations. Radiation hardening of devices and SEU tolerance approaches have alleviated the problem somewhat. It is still grave. Single event upset must be considered in all future space, missile, and avionics systems.

The early “common knowledge” of the effects was based on two papers. The paper by Binder, Smith, and Homan presented the basic information for cosmic ray induced upsets [1975]. They discussed the basic mechanisms and circuit effects, the cosmic ray environment, including the effects of shielding, and a basic approach to cosmic ray event rate. A paper by Petersen presented the proton environment with the variation in altitude and the effects of the South Atlantic anomaly and included the effects of shielding [1981]. He then discussed the possible contributions of the various proton reactions in silicon and presented calculations of proton induced upset rates.

Much of the interest has been driven by developments such as:

- The critical errors caused by cosmic ions in the Voyager and Pioneer probes.

- The necessary retrofits, at great expense, of the Landsat D and Galileo systems due to heightened concern over single event upsets.

- The errors in the guidance system of the Hubble space telescope as its orbit carries it through the earth's radiation belts, requiring frequent scrub and reload of the guidance system.

- The loss of the Japanese satellite “Superbird” due to SEU followed by operator error [1992].

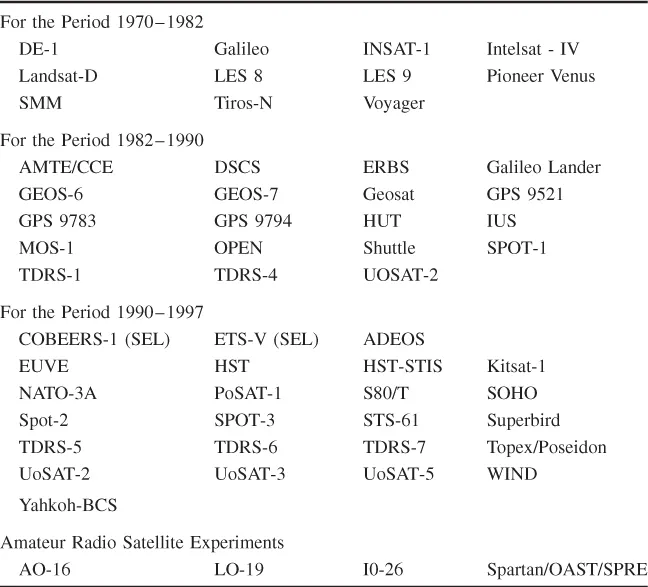

Table 1.1 lists a sampling of other space programs for which single event effects have had an impact. Some of these events were collected by Bedingfield and co-workers [1996]. Ritter has also discussed some of these events [1996].

Table 1.1 A Few of the Spacecraft for Which Single Event Effects Have Had an Impact

There was a parallel set of problems for ground based systems as described by Ziegler [2004]. Soft errors from radiation are the primary limit on digital electronic reliability. This phenomenon is now more important than all other causes of computing reliability put together. Since chip single event rates (SERs) are viewed by many as a legal liability (selling something that you know may fail), the public literature in this field is sparse and always makes management nervous [2004, Preface and Chapter 1].

SEU in space originates from two sources in the natural environment. Satellites at geosynchronous orbit and corresponding regions outside Earth's radiation belts experience upsets due to heavy ions from either cosmic rays or solar flares. The natural cosmic ray heavy ion flux has approximately 100 particles/cm2 per day. In very sensitive devices this flux can lead to daily upsets. Many devices can be upset in these environments at a rate of about 10−6 upsets/bit-day.

Also, upsets can occur within the proton radiation belts. Even though energy loss rates by direct ionization from protons are too low to upset most devices, proton induced nuclear reactions in silicon can result in heavy recoil nuclei capable of upsetting most memory cells. About one proton in 105 will undergo a nuclear reaction capable of SEU. Considering the large population of high energy protons capable of causing these reactions, proton induced upsets become a significant SEU mechanism. In the heart of the proton belts there are about 107 to 109 protons/cm2 per day with energies above 30 MeV (approximately the minimum energy that will penetrate a spacecraft and then cause upsets). Thus, for example, a 1K memory with a proton upset cross section of 10−11 cm2 per bit would have 10 upsets per day in the most intense part of the belt.

As the cosmic rays penetrate the atmosphere, there is a chain of nuclear reactions that produce high energy neutrons and protons. A nominal figure is 6000 neutrons per square centimeter per hour at 40,000 feet altitude and 45 degrees latitude. In the 1990s these were shown to produce single event upsets in complex integrated circuits in avionics equipment.

There are a variety of possible single event effects (SEEs). These are important as they can cause malfunctions in microelectronics devices operating in the space ionizing radiation environment. The principal effects are upset, transients, and latchup, but the others need also to be kept in mind. The basic effects are as follows:

| SEU | UPSET | Temporary change of memory or control bit |

| SET | TRANSIENT | Transient introduced by single event |

| SEL | LATCHUP | Device latches in high current state |

| SES | SNAPBACK | Regenerative current mode in NMOS |

| SEB | BURNOUT | Device draws high current and burns out |

| SEGR | GATE RUPTURE | Gate destroyed in power MOSFETs |

| SEFI | FUNCTIONAL INTERRUPT | Control path corrupted by an upset |

| MBU | MULTIBIT UPSET | Several bits upset by the same event |

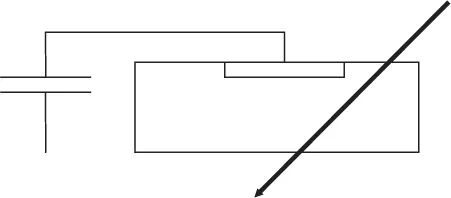

Single events acquire that name because they depend on the interaction of a single particle. Most other radiation effects depend on the dose or damage deposited by large numbers of particles. SEEs can be caused by the passage of a single heavy ion—a cosmic ray in space, for example. As the cosmic ray passes through the silicon of the device, it deposits a track of ions. In space the cosmic rays are ordinarily energetic enough that they pass through the device. If these resulting ions are in the presence of the natural or applied field in an electronic device, they are collected at the device electrodes. See Figure 1.1. This produces an electric pulse or signal that may appear to the device as a signal to which it should respond. If the electrical characteristics of the device are such that the signal appears valid, then there may be a bit upset or the production of a signal in a logic device that triggers a latch later in the device.

Figure 1.1 Ionization path due to direct passage of a heavy ion.

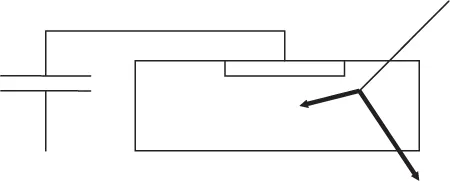

High energy protons can also initiate single event effects. It is not the proton passage that produces the effect. The proton itself produces only a very small amount of ionization. Very few devices are sensitive enough to respond to the proton ionization. However, 1 proton in 105 will have a nuclear reaction in the silicon device. These reactions can produce heavy ions that in turn can deposit enough energy to cause upset. See Figure 1.2. Although this seems like a very small number of cases, in space the protons in the proton radiation belts are intense enough so that they can cause many more upsets than the heavy ion cosmic rays in the same environment.

Figure 1.2 Ionization paths due to proton reaction in a device.

The basic concepts are similar for both heavy ion and proton induced upsets. The prime emphasis in the present work is the heavy ion induced upsets. We will also discuss proton and neutron upsets for comparison later. The prediction of single event effect rates depends on a number of independent models of various aspects of the phenomena involved.

Single event effects can be thought of as one of nature's ways of enforcing Murphy's Law. They can occur at any time, at any place in an electronic system. They do not depend on the cumulative exposure to the space environment and are as likely to occur during or shortly after launch as after a long time in orbit. As for location, the sorrowful words of one space system designer express it: “I know that you said I was going to have upsets, but I didn't expect an upset in that bit.”

Because of these and other real world problems in space systems due to cosmic ions, an understanding of single particle errors in integrated circuit (IC) electronics has become an important part of the design and qualification of IC parts for space-based use.

The issue becomes even more important as device dimensions scale, and denser, more powerful integrated systems are placed in space or satellite applications. Electronics is reaching integration levels where a single bit of information is represented by an extremely small value of charge, and noise margins are very tight. For example, if a typical dynamic random access memory (DRAM) cell can tolerate approximately 100 mV of noise on the bit storage node with 100 fF (10−15 farads) of storage capacitance, then this value of noise corresponds to a charge of only 62,500 electrons. Any perturbation of this delicate balance by an impinging cosmic ion is intolerable. So, a recognition of, and familiarity with, the effects of space radiation on the electronics to be placed in that hostile environment is essential. Single event modeling plays a key role in the understanding of the observed-error mechanisms in existing systems, as well as the prediction of errors in newly designed systems.

There are two different aspects of interest. First is the analysis of various types of single event experiments to help understand the phenomena. Second is the modeling of the various aspects of the phenomena that allow prediction of SEE rates in space.

1.2 Analysis of Single Event Experiments

1.2.1 Analysis of Data Integrity and Initial Data Corrections

Single event experime...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Chapter 1: Introduction

- Chapter 2: Foundations of Single Event Analysis and Prediction

- Chapter 3: Optimizing Heavy Ion Experiments for Analysis

- Chapter 4: Optimizing Proton Testing

- Chapter 5: Data Qualification and Interpretation

- Chapter 6: Analysis of Various Types of SEU Data

- Chapter 7: Cosmic Ray Single Event Rate Calculations

- Chapter 8: Proton Single Event Rate Calculations

- Chapter 9: Neutron Induced Upset

- Chapter 10: Upsets Produced by Heavy Ion Nuclear Reactions

- Chapter 11: Samples of Heavy Ion Rate Prediction

- Chapter 12: Samples of Proton Rate Predictions

- Chapter 13: Combined Environments

- Chapter 14: Samples of Solar Events and Extreme Situations

- Chapter 15: Upset Rates in Neutral Particle Beam (NPB) Environments

- Chapter 16: Predictions and Observations of SEU Rates in Space

- Chapter 17: Limitations of the IRPP Approach

- Appendix A: Useful Numbers

- Appendix B: Reference Equations

- Appendix C: Quick Estimates of Upset Rates Using the Figure of Merit

- Appendix D: Part Characteristics

- Appendix E: Sources of Device Data

- References

- Author Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Single Event Effects in Aerospace by Edward Petersen in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Technology & Engineering & Electrical Engineering & Telecommunications. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.