Part I: The business of investing in blue chip shares

Chapter 1: What is an investor?

I always like to start any discussion by defining terms, just to make sure we’re all on the same page (excuse the pun). So let’s start with a succinct definition of the word invest, taken directly from the fourth edition of the Australian Concise Oxford Dictionary: Apply or use money for profit.

That sounds simple enough, but to really understand the full impact of this statement we need to answer some other questions first and, while they may seem completely unrelated, I would suggest they are not.

• What is a worker?

• What is a manager?

These seem like simple enough questions, but if we probe beyond the brief and obvious answers, we will uncover some very interesting definitions and distinctions.

Worker

Put very simply, a worker is someone who works for someone else in exchange for money. But if we want to be a little more precise about this apparently straightforward function, then we could also say that a worker is someone who sells his or her time for money, and that time includes both that person’s labour and expertise. A typical working situation would be an individual who spends 40 hours per week working for someone else in exchange for approximately $65 000 per year. This is a typical situation, given that these parameters are based on the current Australian averages for hours in a working week and annual wages.

The average person will spend about 40 years of his or her life (from the age of 20 to age 60) working for someone else in order to finance their lifestyle and, hopefully, their retirement. For our purposes, we will define a worker as someone who is directly involved in the process of manufacturing a product or supplying a service. A self-employed person is someone who is a self-managed worker — that is, he or she both manages and is directly involved in the process of manufacturing a product or supplying a service. But if, for instance, someone oversees the production of goods but doesn’t have to be directly involved in the production process itself, then he or she would fit into the next category — manager.

Manager

A manager is someone who controls a system or a process as opposed to being directly involved in the process itself. While it may be argued that a management role is in fact a form of work, and therefore a manager is a worker, for the purpose of this discussion we will define working and managing as two distinctly separate functions or roles. For example, although managing my investments does take time and some degree of effort, it would be inaccurate and somewhat misleading to say that I’m working my investments.

Investor

Now that we’ve clarified the difference between these two functions, let’s apply this understanding to acquiring money. In the first instance we have the worker who sells his or her time for income; this is the most common and conventional way for any of us to acquire money and unfortunately very few of us go beyond this simple method of feeding and clothing ourselves.

But the few of us who do, see ourselves as managers where we control systems or processes that generate money — we are businesspeople. Harking back to the example of my investments, I manage (as opposed to work) my portfolio of blue chip shares, which takes about 20 minutes per week. Or, to put it another way, someone who manages a system or process that generates money is said to be making money as opposed to a worker who sells their time to someone else to earn money.

Now we come to the meat of the matter, because any business that utilises financial products, such as shares and property, is said to be an investment business. And finally, anyone who manages an investment business is an investor and they are applying or using money for profit.

While this explanation of what an investor is may all seem very longwinded, it is of the utmost importance that investors see themselves as businesspeople if they want to be successful.

And now we need to differentiate between investors who manage their own affairs and those who have others manage their money — and it’s all a question of control.

Control

Unfortunately the average individual assumes that others have the expertise and resources that they don’t — a common and erroneous assumption (also one that the investment industry loves to feed on through clever advertising). Although many people do lack the necessary knowledge, it can be easily acquired through books such as this one; you would be surprised at the vast array of resources available to the average do-it-yourself (DIY) investor.

It is often said and it is very true that no-one will take better care of your money than you will. I’ll add to this: you can get someone else to make investment decisions for you, but ultimately the responsibility for your money stays with you. Advisers are paid to give advice (for which they are responsible), but you will find it very hard to hold them accountable for your money if anything goes wrong, such as the losses suffered by shareholders in the failure of the insurance behemoth HIH Insurance Limited.

But given that you’re reading this book, I think it’s a fairly safe assumption on my part that you are more willing than most to become a self-manager of your financial situation. And it may interest you to know that the reason for the current boom in DIY investment is because many self-managed DIY superannuation funds are reportedly doing far better than many managed investment vehicles.

There are several reasons for this: DIY investors aren’t as restricted as fund managers when it comes to investment tactics; DIY funds don’t attract many of the fees that the managed funds charge; and a DIY investor’s sole motivation is the performance of the fund and, in the vast majority of cases, nothing else.

Fund managers

Of course at some point or through circumstances, we’ve all had to outsource the management of part if not all of our investment capital to a third party. Most commonly it’s when we got our first job and we had to make contributions to a compulsory superannuation fund. So let’s take a brief look at some of the key issues associated with employing someone else to manage your money.

If you’ve ever made enquiries about joining a managed fund then you were probably shown a glossy brochure containing a pie chart giving the breakdown for allocating capital to different investment media, such as 40 per cent to property, 50 per cent to Australian equities and 10 per cent to fixed deposits. These pie charts are often far more complex than this and will even delve into capital allocation per industry sector and residential property versus commercial property and so on.

But here’s the silly bit: because they’ve disclosed these allocations to you when they signed you up to the fund, they are committed to them. Hence if the stock market goes into a sustained decline then your money will go into a sustained decline along with it. And many investors well know the pain of being exposed to shares during 2008, when the market lost nearly half its value.

This is why it’s so important when someone else is managing your money to have regular interviews with your financial adviser so you can authorise any changes they need to make in the event of changes in the investment environment. Modern disclosure and compliance rules mean that fund managers can’t necessarily take your money out of the market, even when that may be the best course of action.

Of course, as a DIY investor you can withdraw your money from the market, because you aren’t subject to the same disclosure rules. The reason for this is quite simple, as the idea of disclosure to yourself would be a bit silly.

Anyway, having been directly involved in funds management myself, I can personally attest to the fact that the primary concern of many managed funds is not performance. This is partly due to the fact that the fees charged by most funds are directly proportional to the amount of capital under management as opposed to their performance, and partly due to the cost of meeting regulatory requirements.

Funds management companies will typically put their energies into attracting new money into their funds rather than into achieving the best possible performance, as it is usually the former that primarily determines their profitability. I do appreciate, however, that these two objectives aren’t entirely mutually exclusive.

Then there are the administrative and compliance issues to deal with that, unfortunately, can have considerable sway over the design of an investment strategy. In other words, an investment strategy can be compromised (read: watered down) for the sake of streamlining the administration processes, minimising overheads and reducing or eliminating potential compliance issues.

As you can see, employing someone else to manage your money is actually a bit more of a minefield than most people would imagine. Suffice it to say that even when we employ others to manage our money for us, we are still stuck with the task of managing the managers. Consequently, whether we manage our own money or let others do it for us, it pays to have a good working knowledge of the business of investing and what we are investing in.

Self-management

So let’s take a look at how easy it is to manage your own portfolio of blue chip shares using a very simple set of criteria. Now this simple set of criteria is designed to identify what is commonly referred to as growth stocks — these are shares that we would buy in the hope that the share price will rise over time and we will realise capital growth: hence the name growth stocks.

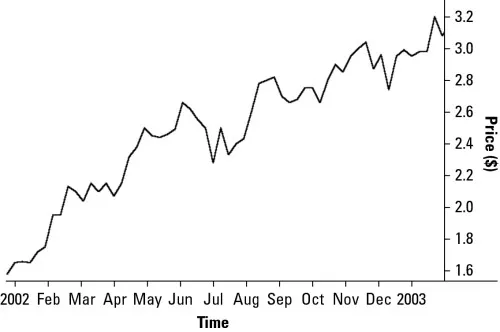

Our main criterion is this: we want to identify quality blue chip companies where the share price is trending up. This means that we want large capitalisation companies that are financially very sound — that is, blue chip companies — where the share price is already rising in value. More specifically, where the share price has already risen over the course of at least one year. This is a very important point because, if the share price is already rising, then the balance of probability suggests it will continue to do so. The chart in figure 1.1 is a typical example of the sort of price activity we’re looking for.

Figure 1.1: example of a weekly price chart

Source: MetaStock.

If this all sounds simple then that’s because it is. The first thing I point out to anyone who wants to learn about the stock market is that it’s not at all complicated, but that is in fact the problem. Most people won’t hold with simple truths because they assume that success can only be achieved through complexity — otherwise everyone would be doing it, right? Wrong. First, most people won’t take on the risk of failure and, second, success in most cases comes from having the discipline to stick with simple ideas that work.

I can give you the simple ideas that work, but dealing with the risk of failure and having self-discipline can only come from within...