eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1

Basic Research

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1

Basic Research

About this book

Now part of a two-volume set, the fully revised and updated second edition of The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1: Basic Research provides comprehensive coverage of the basic research relating to infant development.

- Updated, fully-revised and expanded, this two-volume set presents in-depth and cutting edge coverage of both basic and applied developmental issues during infancy

- Features contributions by leading international researchers and practitioners in the field that reflect the most current theories and research findings

- Includes editor commentary and analysis to synthesize the material and provide further insight

- The most comprehensive work available in this dynamic and rapidly growing field

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Wiley-Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, Volume 1 by J. Gavin Bremner, Theodore D. Wachs, J. Gavin Bremner,Theodore D. Wachs in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychologie & Psychologie du développement. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Introduction to Volume 1: Basic Research

When plans were made for the first edition of the Blackwell Handbook of Infant Development, difficult choices had to be made regarding which topics to include. Despite the fact that the original volume was quite considerably over the agreed length when it went to the publisher, there still were significant gaps in coverage. In the period since its publication in 2001 there have also been continuous gains in our understanding of infant development, making it an even harder task to cover all the major aspects of infant development in one volume. For the second edition it was clear we had to do something to deal with this sheer volume of research and knowledge. Sacrificing depth of coverage did not seem an option. So the solution we arrived at was to move to a two-volume format, with volume 1 covering basic research and volume 2 covering applied and policy issues. We made this decision with some misgivings. After all, it could be argued that by making this split we are reinforcing the relative isolation of applied and basic work. However, we were aware that readers were already selective in what they read within a single volume, so felt that splitting the material into two volumes should not have any major effect, particularly if we took pains to cross-reference chapters between as well as within volumes.

The clear gain of the two-volume format is that we have been able to add 10 new chapters in total. As basic research was most fully represented in the first edition, most of the new chapters are in volume 2. However, volume 1 includes chapters on four topics not covered in the first edition: intermodal perception, perceptual categorization and concepts, imitation, and cultural influences.

The chapters in volume 1 are organized into three parts: perceptual and cognitive development; social cognition, communication, and language; and social-emotional development. These categories very much reflect the groupings of posters and papers at conferences on infancy, but one of the noticeable developments in the field is towards greater integration between research foci that were somewhat isolated in the past. In the case of the present collection of chapters, there are, for instance, links to be seen between face perception (part I, chapter 2) and imitation (part II, chapter 11), face perception and awareness of other minds (part II, chapter 12), and between brain development (part I, chapter 9) and awareness of other minds. These examples by no means form a comprehensive list. The likelihood is that this cross-fertilization will continue, in part through a general tendency for research to cross traditional boundaries within the discipline, but also through the influence of concepts in neuroscience, for instance, research on the mirror neuron system leading to new attempts to integrate cognitive and social development in infancy.

As with the first edition, our aim has been to make the book accessible and informative to a wide audience. Although each chapter addresses current work in a scientifically advanced way, we and the authors have attempted to achieve an approach and writing style that does not rely on prior knowledge of the topic on the part of the reader. Given the relatively high level at which chapters are pitched, we anticipate that the handbook will provide a thorough overview of the field that will be particularly useful to graduate students, advanced undergraduates, and to university staff who teach infancy research but who either do not do research in the field or who are confident only in a limited area. We hope it will also be attractive to academics who are looking for a high-level treatment of current theoretical issues and cutting-edge research.

We open the volume with a chapter by Alan Fogel that sets infancy in theoretical and historical context. This is a revision of his chapter that closed the first edition of the handbook. This time we felt that it was appropriate to place this chapter at the beginning as a scene setter, before the three parts containing the chapters on specific aspects of infant development. Opening with Bronfenbrenner’s Ecological Systems Theory, Alan Fogel points out how at each of the four levels of this system (microsystem, mesosystem, exosystem, and macrosystem) there have been important changes through history. Within this framework he indicates how the nature and our images of infancy have changed from prehistoric times to the present, and ends with some speculations regarding the future of infancy. Important changes have occurred across historical time in how infants are thought of, a key factor being the relatively late emergence of the concept of the individual. However, a common theme that exists across time is the constant come and go between romantic and empirical approaches to infancy.

For cataloguing purposes, the editorial order is alphabetic for both volumes. However, Gavin Bremner had editorial responsibility for most chapters in volume 1 and Ted Wachs had editorial responsibility for all chapters in volume 2.

J. Gavin Bremner and Theodore D. Wachs

1

Historical Reflections on Infancy

Our daughter was the sweetest thing to fondle, to watch, and to hear. (Plutarch, Rome, second century, BCE)

What is best for babies? Cuddling and indulgence? Early training for independent self-care? The answer depends upon the beliefs that people have about babies. Beliefs about infants and their care differ between cultures and they have changed dramatically over historical time within cultures. The contemporary technology of infant care in Western society, for example, first appears in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, with an increase in pediatric medical care, advice books for parents, parental devotion to the individuality of each child, books written especially for young children, and other infant care products and resources.

Why is it important to understand the historical origins and historical pathways of beliefs about infants and their care? Cultural history is vast in its domain, encompassing beliefs and values about human rights, morality, marriage and family, war and peace, love and death. Beliefs about infants are important because to raise a baby is to plant a seed in the garden of culture. We bring up babies in ways that are consistent with responsible childhood and adult citizenship.

Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) Ecological Systems theory suggests how infants are embedded in networks of socio-cultural processes and institutions that have both direct and indirect impacts on infant development. Bronfenbrenner defined four levels of system functioning between persons:

The microsystem is made up of all the relationships between the person and his or her environment in a particular setting. For example, all of the transactions that take place between the child and the physical and social environment of the family or school form a microsystem.

The mesosystem includes the relationships between the major settings in which children are found. An example would be the interaction between the family and the day care center. A child who is experiencing many difficulties in day care is likely to force the family to have more interactions with the center’s teachers and administrators, and those family–school interactions should in turn have an effect on the child’s functioning.

The exosystem extends the mesosystem to include other social systems that do not contain the developing child but have some effect on him or her. The world of work, neighborhood institutions, the media, the government, the economy, and transportation affect the functioning of the family, school, and other social settings in which children are found.

The macrosystem contains all of the various subsystems that we have been discussing. It contains all of the general tenets, beliefs, and values of the culture or subculture and is made up of the written and unwritten principles that regulate everyone’s behavior. These principles – whether legal, economic, political, religious, or educational – endow individual life with meaning and value and control the nature and scope of the interactions between the various levels of the total social system.

Each of these systems has a history that is embedded within the larger history of a society. The “culture” of infancy, at any particular period in historical time, can be thought of as the complex set of relationships between and within each of these systems. In this chapter, I do not go into details about each of these levels of the system across historical time. Rather, the goal is a more general view of the macrochanges that have occurred across tens of thousands of years.

This chapter is based on research from secondary sources. These include the work of historians and anthropologists who have studied the primary sources of historical evidence, as well as translations into English of original historical documents. For prehistorical data, I rely on evidence from observers of modern hunter-gatherer societies as well as anthropological data. For the historical period, the focus will be on the work of historians and translators of original documents of Western culture (Judeo-Christian, Greek and Roman, and later European and American societies). This research approach may bias my interpretations in favor of the historian or translator who worked with the original documents and artifacts. A different point of view may arise from the work of a scholar who is competent to examine the evidence more directly.

This chapter highlights one major theme that was salient to me in collecting these materials, the historical continuity of a dialectic between empirical and romantic beliefs about infants. On the empirical side are beliefs related to the early education, training, and disciplining of infants to create desired adult characteristics and to control the exploration, shape, and uses of the body. Romantic beliefs favor the pleasures of babies and adults. Romantic ideas advocate indulgence in mutual love and physical affection in relationships, they show a respect for the body and its senses and desires, and the freedom of expression of all of the above. Although the terms empiricism and romanticism do not come into the English language until the eighteenth century, the earliest historical records reveal belief systems that will later come to be labeled as empirical or romantic.

The chapter is divided into the following sections: The prehistory of infancy (1.6 million to 10,000 years ago), early civilizations (8,000 BCE to 300 ce), the Middle Ages and Renaissance (third to sixteenth centuries), the Enlightenment (seventeenth to nineteenth centuries), and the recent past (twentieth century). The chapter concludes with a speculative section on the possible future of beliefs and practices about babies.

Prehistory of Infancy: 1.6 Million to 10,000 Years Ago

It is currently thought that all humans are descended from a small population of huntergathers who first appeared in Africa during the Pleistocene epoch. The Pleistocene lasted between 1.6 million years ago and 10,000 years ago. Beginning about 10,000 years ago and continuing until the present time, humans gradually abandoned nomadic patterns and began to occupy permanent settlements and to develop agriculture. Homo sapiens hunter-gatherer societies first appeared about 100,000 years ago and were descended from a long line of other human species that arose at the beginning of the Pleistocene.

By about 35,000 years ago, homo sapiens sapiens hunter-gatherer groups existed in most locations in the old world, in Australia, and in the Americas. Societies of this period were composed of small bands of about 25 humans who sustained themselves by hunting game and gathering wild roots and plants to eat. They would roam typically less than 20 miles (30 kilometers) and it was rare to encounter another group. Generations lived their lives within this small sphere of people and place. Hunter-gatherer societies are believed to have been the only form of human society during the entire Pleistocene epoch. They did not leave artifacts or other documentation of their infant care practices (Wenke, 1990). Relatively few such societies survive today. While there is some controversy about whether surviving hunter-gatherers are similar to prehistorical hunter-gatherers, these contemporary groups are considered to be reasonable approximations to prehistorical lifestyles (Hrdy, 1999; Wenke, 1990).

The human ecology during the Pleistocene is considered to be the environment of evolutionary adaptedness, a term devised by John Bowlby the founder of attachment theory (Bowlby, 1969). This is the African Pleistocene environment in which the human adult–infant bond evolved for over a million years, an environment with large populations of predators who could easily kill and eat a baby. In order to protect the infant from this and other dangers, the infant was carried in a sling or pouch at all times, never left alone, and the caregiver responded immediately to fussiness in order not to attract the attention of predators. As a consequence, humans evolved a mother–infant relationship with continuous touch and skin-to-skin contact, immediate attention to infant signals, and frequent breast feeding (Barr, 1990).

The present day !Kung bushmen, a hunter-gatherer group living in the Kalahari desert in Africa, have been observed extensively. !Kung women carry their infants in a sling next to their bodies at all times. They breast feed on demand, as much as 60 times in a 24 hour period. The infant sets the pace and time of breast feeding.

Nursing often occurs simultaneously with active play with the free breast, languid extension flexion movements in the arms and legs, mutual vocalization, face-to-face interaction (the breasts are quite long and flexible), and various forms of self-touching, including occasional masturbation. (Konner, 1982, p. 303)

Infants also receive considerable attention from siblings and other children who are at eye-level with the infant while in the sling.

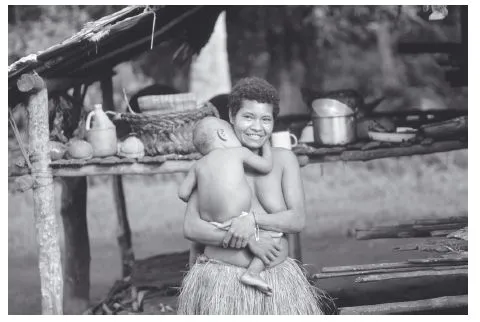

Figure 1.1 Infants in hunter-gatherer societies are in nearly constant skin-to-skin contact with people, as shown with this woman holding a baby in Huli village, Papua New Guinea.

Source: Photo © Amos Nachoum/Corbis.

When not in the sling, infants are passed from hand to hand around a fire for similar interaction with one adult or child after another. They are kissed on their faces, bellies, genitals, are sung to, bounced, entertained, encouraged, and addressed at length in conversational tones long before they can understand words. (Konner, 1982, p. 302)

The high rate of nursing prevents infant crying and has a natural contraceptive effect to prevent the birth of another child while the younger one still requires mother’s milk. Births are spaced every 4 or 5 years (Konner, 1982; Wenke, 1990). The present-day Elauma of Nigeria are also hunter-gatherers (Whiten & Milner, 1986). Three-monthold Elauma infants spend almost all their time, whether awake or asleep, in physical contact with an adult or within three feet of the adult. Elauma mothers carry their babies with them while the mothers go about their daily chores (See Figure 1.1).

A similar account is offered from observations of the Fore people of New Guinea, a rain-forest hunter-gatherer group who remained isolated from the outside world until the 1960s. This group displays a “socio-sensual human organization [italics added] which began in infancy during a period of almost continuous, unusually rich tactile interaction” (Sorenson, 1979, p. 289). Play with infants includes “considerable caressing, kissing, and hugging” (p. 297).

Not only did this constant “language” of contact seem readily to facilitate the satisfaction of the infant’s needs and desires but it also seemed to make the harsher devices of rule and regimen unnecessary. Infant frustration and “acting out,” traits common in Western culture, were rarely seen. (Sorenson, 1979, p. 297)

Because of this indulgence of the senses and a relative lack of overt discipline, huntergatherer societies exemplify a primarily romantic culture. Observations of weaning both in the !Kung and the Fore, however, suggest that the training of infants – empirical beliefs and practices – is also important. Although !Kung adults report memories of the difficulty of losing their close contact with their mother during weaning, they also report that these feelings were alleviated by the presence of other adults, siblings, and peers. Weaning occurs when the mother becomes pregnant with the next child. Adults believe that with the onset of pregnancy, the mother’s milk will harm the nursing child and must be reserved for the unborn child. In the words of Nisa, a !Kung woman who spoke about her life,

When mother was pregnant with Kumsa, I was always crying, wasn’t I? One day I said, “Mommy, won’ t you let me have just a little milk? Please, let me nurse.” She cried, “Mother! My breasts are things of shit! Shit! Yes, the milk is like vomit and smells terrible. You can’t drink it. If you do, you’ll go ‘Whaagh … whaagh …’ and throw up.” I said, ‘No, I won’t throw up, I’ll just nurse.’ But she refused and said, ‘Tomorrow, Daddy will trap a springhare, just for you to eat.’ When I heard that, my heart was happy again. (Shostak, 1983, p. 53)

Even here, in the most romantic of human lifestyles, in which the body and its senses are indulged and in which children receive very little discipline or restrictions, empirical beliefs are present in some form. The discourse between the romantic and the empirical may be a law of nature, derived from the simple truth that elders require of children some sacrifice if they are to grow into full coparticipation. If the sacrifice is done in the flow of a balanced dialogue, it will soon be followed by a new and surprising indulgence. The springhare helps Nisa to let go of her tragic loss and gives her a feeling of sharing in the more adult-like ritual of hunting. There is also evidence that hunter-gatherer groups occasionally used infanticide – the deliberate killing of unwanted infants and an extreme form of empiricist practice – for infants who were sick or deformed, those who could not have survived under the rigors of the harsh environment.

For most of human evolution, then, people lived close to the earth, either on open ground, in and near trees, in caves and other natural shelters. They were directly attuned to the earth, its climate, and its cycles. The basic elements of earth, air, fire, and water had enormous practical and spiritual significance. So far as we know, people did not distinguish themselves as separate from their ecology but as part of it, no different or more valuable than the basic elements, the plants, and animals (Shepard, 1998).

For people of the Pleistocene, the environment was not an objective collection of rocks and creatures; it was a form of consciousness in which there was an unquestioned and nonjudgmental sense of connection to all things. This has been called a partnership consciousness as opposed to the dominator consciousness that appeared later (8,000–3,000 BCE) with the formation of towns, social hierarchies, power structures, and warfare (Eisler, 1987).

Beginning about 35,000 years ago, humans developed what has been called mythic culture, which saw the origins of symbols, representations, language, and storytelling that served as a way of making sense of the universe. Myths worldwide express the belief that the world, and all its creatures including humans, is sacred. In mythic culture, the universe cannot be changed or shaped. Myths served to integrate and explain the various facets of life and death that were accepted as they were and never questioned (Donald, 1991).

At this time, the first representational art and artifacts began to appear, in the form of cave and rock paintings and small figurines (Wenke, 1990). The paintings depicted animal and human forms, possibly spiritual or mythic figures. The figurines were typically about palm size and represented women with prominent breasts, hips, and vaginas. They were believed by many to represent fertility, while others suggest that they represented a goddess-type deity and a matriarchal social order (See Figure 1.2). These figurines may have conferred fertility on individuals and at the same time celebrated the mysterious life-giving power of the female.

It is probably during this phase of human prehistory that rituals marking the life transitions of birth and death, along with mythical interpretations of their meaning, first appeared. Although there is relatively little archeological evidence, we can learn a great deal about birthing rituals and practices from studies of living tribal societies. In many tribal societies today, for example, birth occurs in the company of women, close female relatives and older “medicine” women, shamans who are expert in the practice of childbirth. Plant and animal extracts are used for the pains of pregnancy and childbirth. In some matriarchal societies, husbands are asked to change their behavior when their wives are pregnant, a practice called couvade. Fathers in the Ifugao tribe of the Philippines are not permitted to cut wood during their wives’ pregnancy (Whiting, 1974).

Healing practices and prayer rituals were created in prehistory to foster healthy fetal development and childbirth. One common practice, used by the Laotians, the Navaho of North America, and the Cuna of Panama, among others, is the use of music during labor. Among the Comanche and Tewa, North American Indian tribes, heat is applied to the abdomen. The Taureg of the Sahara believe that the laboring mother should walk up and down small hills to allow the infant to become properly placed to facilitate delivery. Taureg women of North Africa deliver their babies from a kneeling position (Mead &am...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Series page

- Title page

- Copyright

- List of Contributors

- Introduction to Volume 1: Basic Research

- 1: Historical Reflections on Infancy

- PART I: Perceptual and Cognitive Development

- PART II: Social Cognition, Communication, and Language

- PART III: Social-Emotional Development

- Author Index

- Subject Index

- Contents of Volume 2