- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics

About this book

A practice-oriented desktop reference for medical professionals, toxicologists and pharmaceutical researchers, this handbook provides

systematic coverage of the metabolic pathways of all major classes of xenobiotics in the human body. The first part comprehensively reviews

the main enzyme systems involved in biotransformation and how they are orchestrated in the body, while parts two to four cover the three

main classes of xenobiotics: drugs, natural products, environmental pollutants. The part on drugs includes more than 300 substances from

five major therapeutic groups (central nervous system, cardiovascular system, cancer, infection, and pain) as well as most drugs of abuse

including nicotine, alcohol and "designer" drugs. Selected, well-documented case studies from the most important xenobiotics classes illustrate general principles of metabolism, making this equally useful for teaching courses on pharmacology, drug metabolism or molecular

toxicology.

Of particular interest, and unique to this volume is the inclusion of a wide range of additional xenobiotic compounds, including food supplements, herbal preparations, and agrochemicals.

systematic coverage of the metabolic pathways of all major classes of xenobiotics in the human body. The first part comprehensively reviews

the main enzyme systems involved in biotransformation and how they are orchestrated in the body, while parts two to four cover the three

main classes of xenobiotics: drugs, natural products, environmental pollutants. The part on drugs includes more than 300 substances from

five major therapeutic groups (central nervous system, cardiovascular system, cancer, infection, and pain) as well as most drugs of abuse

including nicotine, alcohol and "designer" drugs. Selected, well-documented case studies from the most important xenobiotics classes illustrate general principles of metabolism, making this equally useful for teaching courses on pharmacology, drug metabolism or molecular

toxicology.

Of particular interest, and unique to this volume is the inclusion of a wide range of additional xenobiotic compounds, including food supplements, herbal preparations, and agrochemicals.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Metabolism of Drugs and Other Xenobiotics by Pavel Anzenbacher,Ulrich M. Zanger in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Toxicology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part One: Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics of Drug Metabolism

1

Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes – An Overview

1.1 Introduction: Fate of a Drug in the Human Body

Drugs and, more generally, all substances foreign to the human body enter the organism in many ways. Intentional administration of a drug implies that the route of administration is selected depending on the clinical status of the patient, on the target tissue or organ, and on the chemical nature of the drug. For example, highly ionized compounds cannot easily penetrate barriers such as that of the gastrointestinal tract and therefore should be administered parenterally. Peptides or proteins are degraded to a great extent in the gastrointestinal tract by the action of hydrolytic enzymes and hence are often given to patients in ways other than the most common oral route (e.g., by intranasal application). Intravenous application implies an immediate interaction of a drug with plasma enzymes (e.g., carboxyesterases).

In many cases, the enzymes performing the biotransformation of a drug are needed to convert a parent drug (a prodrug) to the active molecule. Lovastatin – a hypolipidemic drug – is a good example of this process as it requires metabolic activation by carboxyesterases. Carboxyesterases in the plasma, liver microsomes, and liver cytosol convert 18, 15, and 67%, respectively, of the orally given drug to the active hydroxyacid molecule [1].

In general, after its administration a drug should be absorbed; subsequently, it is distributed in the body, often it is also metabolized, and finally excreted. These processes determine the pharmacokinetics of a drug; in other words, the time course of the drug level in the tissue or organ of interest.

The majority of drugs are administered orally and, hence, the uptake of a drug from the gastrointestinal tract is the most frequent way of drug absorption; consequently, the action of liver (and intestinal) drug-metabolizing enzymes starts already in the process of absorption, even before the drug reaches the systemic circulation. The enzymes of drug biotransformation often lower the amount of drug available in the systemic circulation by converting it into metabolites (active, inactive, or with an altered activity) – this process is known as the “first-pass effect.” The enzymes of drug biotransformation often decide the biological availability of a drug (i.e., the level of a drug available at the site of its action). This book focuses on drug metabolism and on the respective enzymes responsible for this process.

However, this is not the only role of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Changes in drug metabolism may be responsible for the incidence of adverse reactions to drugs, such as when a drug’s metabolism is blocked by another compound (e.g., due to competition with another drug – then the level of the “victim” drug may increase and even exceed the toxic levels) or, on the contrary, by induction of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Then, the metabolism of another drug (“victim”), metabolized by the same enzyme, is quicker and it may fail to reach its therapeutic range. This type of drug–drug interaction has been intensively studied as it is a potential reason for failure of pharmacotherapy [2]. The situation may be further heavily influenced by genetic predisposition of a patient to metabolize the respective drug, such as in many examples of drugs metabolized by cytochromes P450 (CYPs). This is, for example, the case for antidepressants metabolized by CYP form 2D6, where the genetically determined ability of a patient to metabolize the drug may lead to effective dose variations approaching an order of magnitude [3]. For example, when a slowly metabolizing patient on a somewhat lower dose of the “victim“ drug takes another drug metabolized by the same CYP2D6 enzyme, both the effects of drug interaction caused by the competition for the enzyme active site and the pharmacogenetic predisposition come into play, and the patient could easily be overdosed. This is why this book deals not only with the respective enzymes and drugs, but also with the pharmacogenetic implications of patients’ predispositions to variations in drug metabolism.

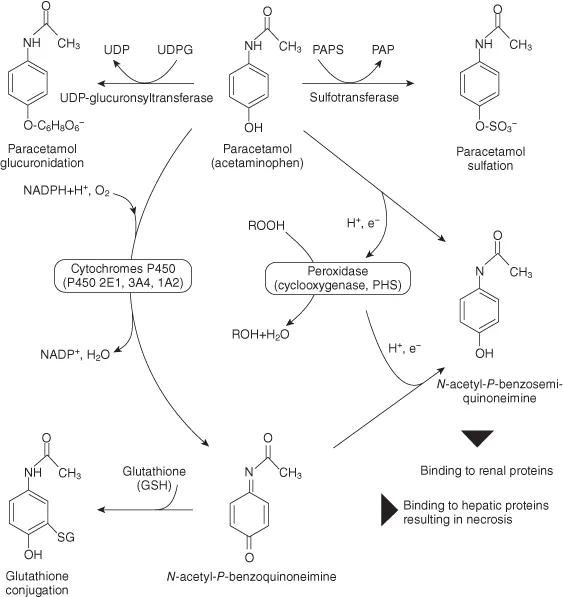

1.2 Classification Systems of Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes According to Different Criteria

Drug-metabolizing enzymes have been traditionally grouped into two main classes, reflecting the fact that a drug is often primarily transformed to a more polar metabolite either by insertion of a polar group into the molecule (e.g., by hydroxylation) or by liberation of an already present functional group (e.g., by demethylation of a hydroxymethyl derivative yielding a free hydroxyl). These “first-phase” reactions are in most cases followed by conjugation reactions (“second phase”) during which the molecule is typically attached to a more polar molecule to facilitate its excretion. Since 1959 when Williams [4] introduced this terminology, it has been shown (with progress in elucidation of the drug metabolic pathways of many drugs) that there are possibly more exceptions to this general rule than expected; for example, some “phase II” reactions may not be preceded by “phase I” biotransformation – morphine that is glucuronidated directly or paracetamol (acetaminophen) that is also predominantly glucuronidated or conjugated with sulfate (Figure 1.1) [5].

Figure 1.1 Pathways of paracetamol (acetaminophen) metabolism. Paracetamol is primarily converted to a sulfate or glucuronide by SULT (with a PAPS coenzyme) and UGT, UDPG is the UDP-glucuronide; oxidation reactions catalyzed by CYPs or peroxidase lead to the formation of reactive toxic products; for detoxication, conjugation with glutathione (GSH) by GST is available under physiological conditions [5].

The original concept of the drug or its metabolite being converted to an even more polar molecule in the “phase II” process is also not generally valid. As has been recently pointed out, for example, the N-acetylation of aromatic amines or the methylation of catechols usually decreases the water solubility of the resulting compounds [6].

The apparent complexity of this problem is also reflected in a classification of biotransformation reactions suggested in [6] based on the chemical nature of the process:

i) Oxidations, including reactions mediated by CYPs and peroxidases, but also by alcohol hydrogenases and others.

ii) Reductions, performed by, for example, ketoreductases and azoreductases.

iii) Conjugations, limited, however, to reactions in which the electrophilic nucleoside-containing cofactors (such as adenosine triphosphate, activated sulfate 3′-phosphoadenosine-5′-phosphosulfate (PAPS), acetyl-CoA, UDP-glucuronic acid, S-adenosylmethionine, etc.) play a crucial role in interactions with nucleophilic sites in a xenobiotic molecule (e.g., the amino or hydroxy group).

iv) Nucleophilic trapping processes, when electrophilic xenobiotics react with cellular nucleophiles – often represented by water or by glutathione (including formation of protein and DNA adducts).

Clearly, the future will show whether the new classification is more viable than the original one.

Figure 1.1 gives an introduction to drug metabolism processes by showing the pathways of paracetamol metabolism. Reactions of the “first phase” involve oxidation of the parent molecule to quinone structures catalyzed by CYPs and peroxidase (cyclooxygenase (COX, also called prostaglandin H synthase); the conjugation processes are both sulfation and glucuronidation (the majority of paracetamol is metabolized by these two reactions) as well as a detoxication reaction by conjugation of glutathione to the toxic and reactive N-acetyl-p-benzoquinone imine (NAPQI).

In the first part of this book, the focus is on the main classes of biotransformation enzymes without attempting to divide or group them into categories. As in most textbooks, the description will start with CYPs as they represent the most important family of drug-metabolizing enzymes. Formation of adducts of activated xenobiotics with biological macromolecules (proteins, DNA, but also polysaccharides) as well as with other structures is not covered here since the aim of this book is to give the interested professional information on the interaction of drugs with enzymes of metabolism and on the related consequences.

1.3 Overview of the Most Important Drug-Metabolizing Enzymes

1.3.1 CYPs

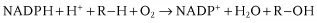

CYPs are the best known drug-metabolizing enzymes [7]. They deserve this attention – more than three-quarters of all known drug oxidations are catalyzed by CYPs and this is certainly not the final count. The oxidation reactions are started by one-electron reduction of the heme iron central atom, which is followed by binding of molecular oxygen. In other words: (i) CYPs are proteins that possess heme in their active site (just as with hemoglobin or other cytochromes), (ii) their function needs electrons to be supplied from a suitable source – another protein having the ability to transfer electrons from NADPH to CYPs (for drug-metabolizing microsomal CYPs, in most cases a flavoprotein), and, finally, (iii) the heme iron should be able to bind molecular oxygen (no wonder – as in hemoglobin), but in this particular case it should be endowed with “magical” force to split the dioxygen and activate it. This “extra” force is provided by donation of electron density coming from a sulfur atom serving as the sixth ligand of the heme iron. To refresh the chemistry of hemes, an iron atom can be bound to six partner atoms or ligands; here, in the resting state, four bonds are occupied by nitrogen atoms of the heme, the fifth bond joins the heme iron to a negatively charged sulfur atom (“thiolate” sulfur) of a Cys amino acid residue from the protein chain and the sixth bond is with an oxygen from a water molecule present in the active center (during the catalytic process, a dioxygen is bound here). The result can be described by a relatively simple equation summarizing the reaction in which the molecular oxygen (dioxygen) is activated and split, yielding a water molecule and a monooxygenated (mostly hydroxylated) substrate. Very recently, the crucial intermediate of this process, the Fe(IV) oxo porphyrin radical species (so-called Compound I of the heme enzymes) has been prepared in high yield from microbial CYP119 [8]. A detailed description of the catalytic mechanism is given in Chapter 2. The reaction summarizing most of the processes in which the CYP enzymes take part can be written as:

The reaction involves the source of electrons (reduced NADPH cofactor with a proton H+), a substrate (R–H), dioxygen, and oxidized NADP+, water, and a monooxygenated or hydroxylated molecule of substrate (R–OH).

CYP enzymes metabolizing xenobiotics are localized in many tissues, typically in the liver, intestines, lung, and kidney, but also in the brain, heart, and nasal mucosa. Subcellular localization of these enzymes is mainly in microsomes (formed after cell disruption from the endoplasmic reticulum); however, drug-metabolizing CYPs are present also in cellular membranes and mitocho...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Related Titles

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Preface

- List of Contributors

- Part One: Biochemistry and Molecular Genetics of Drug Metabolism

- Part Two: Metabolism of Drugs

- Part Three: Metabolism of Natural Compounds

- Part Four: Metabolism of Unnatural Xenobiotics

- Index