![]()

Part I

General Approach to Upper and Lower GI Bleeding

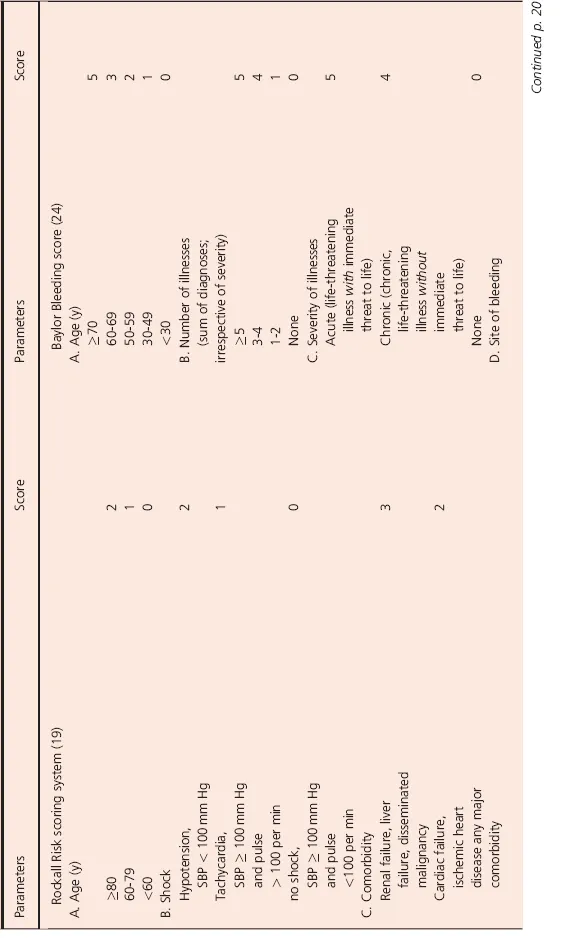

![]()

Chapter 1

Gastrointestinal Bleeding: Presentation, Differential Diagnosis and Epidemiology

Joseph Sung

Institute of Digestive Disease, The Chinese University of Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China

Upper gastrointestinal bleeding (UGIB) represents a substantial clinical and economic burden, with reported incidence ranging from 48–160 cases per 100,000 adults per year (1–3). UGIB commonly presents with hematemesis and/or melena. In cases of severe UGIB, hematochezia (bright red or maroon colored blood per rectum) can be found. Depending on the speed of blood loss, hemodynamic status may be affected in different ways. In patients with severe blood loss in a short period of time, resting tachycardia (pulse > 100 beats per minute), hypotension (systolic blood pressure <100 mmHg) and postural drop in blood pressure (drop in systolic blood pressure of >20mmHg on standing) are evident, leading to dizziness and loss of consciousness in some cases. In patients with mild to modest blood loss over a longer duration of presentation, anemia, malaise and postural changes in pulse and blood pressure are common.

The incidence and prevalence of uncomplicated peptic ulcer have declined in recent years, largely due to the availability of treatments to eradicate Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori), and to the decreasing prevalence of H. pylori infection (4, 5). However, the use of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and other non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) that are associated with adverse gastrointestinal events is becoming more widespread. The mass vaccination against viral hepatitis B in newborns has also led to a decrease in cirrhosis and portal hypertension in high prevalence countries in Asia. As a result, the incidence of variceal hemorrhage due to viral hepatitis has declined, although alcoholic cirrhosis remains an important medical emergency.

Causes of Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding

The most common causes of upper GI bleeding are depicted in large scale surveys (Table 1.1) (6, 7). Peptic ulcer disease usually constitutes slightly over 50% and esophagogastric varices 15–20% (Fig. 1.1). The other important conditions leading to UGIB include Mallory-Weiss tear, angiodysplasias and vascular ectasias, Dieulafoy's lesion, tumors of the upper gastrointestinal tract. In as many as 20% of patients, the diagnosis cannot be ascertained. On the other hand, in around 10% of patients, more than one source of bleeding may be identified.

Table 1.1 Incidence of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage associated with peptic ulcer disease.

Peptic Ulcer and Gastro-Duodenal Erosions

Both peptic ulcers and erosions are defined as a breach of the gastroduodenal mucosa as a result of peptic injuries. Differentiation of ulcers from erosions on endoscopic appearance is often based on the size (at least 5mm) and the presence of appreciable depth in ulcers. Both lesions are mainly caused by Helicobacter pylori infection and the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. With the wide use of aspirin and other anti-platelet agents as prophylaxis against coronary heart disease, cerebrovascular accident and prevention of cancer, the incidence of peptic ulcers related to these drugs are expected to rise. Stress related ulcers develop in patients who are hospitalized for major illness and life-threatening non-bleeding medical conditions. The risk of stress ulcer bleeding is probably higher in those who have respiratory failure and those with a bleeding diathesis. It has also been known that these patients have a higher mortality than those admitted to hospital with primary UGIB. The incidence varies widely in different countries and cohort studies. In recent years, however, evidence suggests that there is an increasing trend of peptic ulcer not related to H. pylori infection or NSAID, so-called non-HP non-NSAID ulcers (8). These patients are older and their risk of recurrent bleeding is higher and associated with higher mortality. The etiology behind this non-HP non-NASID ulcers remains unclear.

Bleeding from gastroduodenal ulcers stop in 90% of cases by the time patients arrive to hospital. However, recurrent bleeding occurs in 30–50% of cases if appropriate treatment is not given.

Incidence of Peptic Ulcer Bleeding

A systematic review of upper gastrointestinal bleeding in 11 studies in Europe, reported on the incidence of complications associated with peptic ulcer extrapolated to the general population (Table 1.1) (9). Reported annual incidences of hemorrhage in the general population ranged from 0.019% (10) to 0.057% (11). A UK database study reported an annual incidence of 0.079% (12). However, this study was confined to individuals older than 60 years, and could therefore not be extrapolated to the population as a whole. Two national audits from the UK extended the analysis to include all causes of upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage and found a higher incidence. Blatchford and colleagues reported an annual incidence of 0.172% (95% CI: 0.165–0.180) in Scotland in 1992/1993 (13). Similarly, an audit performed during a four-month period in hospitals in the UK found an annual incidence of 0.103% (14). In this study, the annual incidence increased from 0.023% in individuals aged under 23 years to 0.485% in individuals aged over 75 years.

The few studies that have examined time trends in peptic ulcer hemorrhage reported no significant change in incidence over time. Bardhan and colleagues observed only a slight decrease in the annual incidence of hemorrhage in the UK, from 0.021% during 1990–1994 to 0.019% during 1995–2000 (10). Van Leerdam and colleagues similarly reported a statistically non-significant decrease in the incidence of both gastric and duodenal ulcer hemorrhage from 1993/4 to 2000 (2). However, Lassen and colleagues reported a slight increase in the annual incidence of hemorrhage in Denmark, from 0.055% in 1993 (95% CI: 0.049–0.062) to 0.057% in 2002 (5). Taha and colleagues studied the incidence of all upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage in individuals taking ASA 75 mg/day in Scotland (15). The annual incidence increased from 0.015% in 1996 to 0.018% in 1999 and 0.027% in 2002.

Mortality of Peptic Ulcer Disease

Mortality after peptic ulcer hemorrhage ranges from 1.7% to 10.8%, depending on the reported series and the average mortality is 8.8%. Increasing age, comorbid illness, hemodynamic shock on presentation, recurrent bleeding and need for surgery are important predictors of mortality in peptic ulcers bleeding after therapeutic endoscopy (16). Furthermore, delay in treatment for over 24 hours may be an important management issue. Recently, two studies from the US indicated that patients admitted after hours exhibited a higher mortality; although observational studies, the authors suggested this association may be related to lower rates of early intervention (17, 18).

However, not all cases of mortality are related to uncontrolled hemorrhage. In a single-center audit from Hong Kong which included 10,428 cases of confirmed peptic ulcer bleeding, only 25% of patients died from bleeding-related cause (e.g. uncontrolled bleeding, died on surgery, post-surgical complication endoscopy related complications, and death within 48 hours after endoscopy) (19). Comorbid illnesses such as cardiac, pulmonary, or cerebrovascular diseases, multi-organ failure or sepsis, and terminal malignancy constituted the majority of causes of death in this series. Therefore, the management of patients with peptic ulcer bleeding should not be focusing only on the control of hemorrhage. It is important to provide supportive care and management of patients' cardiopulmonary conditions. Drugs such as antiplatelet agents and anticoagulants which might be related to the development of peptic ulcer bleeding are often discontinued during UGIB. The early resumption of these drugs should be considered, balancing the risks and benefits of these treatments (20).

Sonnenberg studied mortality data from non-European countries including Argentina, Australia, Chile, Hong Kong, Japan, Mexico, Singapore and Taiwan (21) (Fig. 1.2). The age-standardized death rates in individual countries were tracked from 1971 to 2004. In all countries, there was a decline in gastric and duodenal ulcer mortality. The risk of dying from gastric and duodenal ulcer increased in consecutive generations born between the mid- and end of the nineteenth century and decreased in all subsequent generations. The peak mortality of gastric and duodenal ulcers occurred at the turn of the last century (Fig. 1.1). This decline in mortality which preceded the advent of endoscopic and pharmacological treatment is attributed to the decline in H. pylori infection. The bell shaped peak of ulcer occurrence among consecutive generations born between 1850 and 1950 is related to the interaction between a declining H. pylori infection and an advancing age of patients from these countries. In Europe, The data from the past 50–80 years show striking similarity (22) (Fig. 1.3). The risk of dying from gastric and duodenal ulcers increased among consecutive generations born during the second half of the nineteenth century until shortly before the turn of the twentieth century and then decreased in all subsequent generations. The time trends of gastric ulcer incidence preceded those of duodenal ulcer by 10–30 years. The increase in consumption of NSAID and introduction of potent anti-secretory medications have not affected the long-term downward trends of ulcer mortality. The birth-cohort pattern is the most predominant factor influencing the temporal change of peptic ulcer mortality, probably related to H. pylori carriage rate.

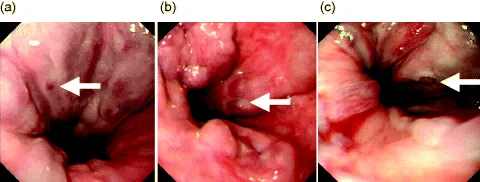

Gastroesophageal Varices

Gastroesophageal varices are often, but not always, the result of portal hypertension. Bleeding from gastroesophageal varices is now widely accepted as a phenomenon of “explosion” instead of “erosion.” Varices develop usually when portal pressure builds up to above 20 mmHg and with a hepatic venous pressure gradient exceeding 12 mmHg, it is associated with a greater risk of continued or recurrent bleeding (23). Thus the risk of hemorrhage is related to the size of the varices, wall thickness and intra-variceal pressure. Several groups have confirmed that variceal size is the most important pro...