eBook - ePub

Plasmid Biopharmaceuticals

Basics, Applications, and Manufacturing

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The book addresses the basics, applications, and manufacturing of plasmid biopharmaceuticals. The survey of the most relevant characteristics of plasmids provides the basics for designing plasmid products (applications) and processes (manufacturing). Key features that the authors include in the book are: i) consistency and clear line of direction, ii) an extensive use of cross-referencing between the individual chapters, iii) a rational integration of chapters, iv) appellative figures, tables and schemes, and v) an updated, but selected choice of references, with a focus on key papers.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Plasmid Biopharmaceuticals by Duarte Miguel F. Prazeres in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Medicine & Pharmacology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: Basics

1

Historical Perspective

1.1 GENE THERAPY

1.1.1 Introduction

Humankind has been plagued with disease for centuries. From the most devastating pestilences such as the ancient black death and smallpox to the modern acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS) epidemic, the suffering and death toll imposed on millions of human beings have continuously challenged medicine. The majority of those great killers of the past were associated with the ecological, nutritional and lifestyle changes brought about by human progress.1 Although not so spectacular and abundant as infectious or acquired diseases, hereditary diseases have always attracted human curiosity. Perhaps this is associated to the tragedy of parents passing on a malady to their own children. Most certainly, medical and scientific communities have been lured by the fact that the origin of many of these hereditary diseases can be traced back to single molecular defects in genes (i.e., they conform to the Mendelian rules of inheritance).2 As written by J. E. Seegmiller, an American pioneer in human genetics, “These disorders are experiments of nature that present unique opportunities for expanding our knowledge of many biological processes. Some of our fundamental concepts of the mechanism of gene action can be traced to basic studies of human hereditary diseases.”3

Against this background, it is thus not surprising to realize that one of the holy grails of medicine e has been to cure hereditary abnormalities by eliminating or correcting the associated defective genes. This idea of “genetic correction” surfaced in the scientific literature shortly after Avery, MacLeod, and McCarty in 1944 described that genes could be transferred within nucleic acids,4 and well before the advent of molecular biology. In an article entitled “Gene Therapy,” and in what was probably one of the first times the two terms have been used together, Keeler realized that plant and animal breeding sometimes results in the permanent correction of hereditary diseases.5 This correction, as he described it, is brought about by the crossing of the afflicted individual with a “normal one,” becoming effective in their offspring and in generations thereafter. At the time, Keeler did not envisage the use of such “gene therapy” to cure human genetic diseases but concluded that the strategy could be applied to correct physical, physiological, and behaviorist gene-based deviations in plants and animals.5 Nevertheless, the notion of correcting genetic defects through breeding could hardly be foreseen as an effective therapeutic technique to treat genetic diseases in man. And, although termed by the author as gene therapy, the process described in his article was very far from the deliberate transfer of specific genes into subjects, which is nowadays readily associated with the concept of gene therapy.

Foreign DNA and genes have been routinely introduced into humans by a number of well-established therapeutic and prophylactic procedures, although in a haphazard and unintentional way. Consider, for instance, Edward Jenner’s smallpox vaccination, a technique developed in 1790 that involved the inoculation into recipients of the vaccinia virus, the agent responsible for cowpox, one of deadliest infectious diseases ever to affect humans.6,7 As a consequence of this new procedure, patients were brought into contact with millions of viral particles, each of them harboring the 223 genes of the vaccinia virus genome. Jenner’s pioneering work opened the way to the development of a steady stream of vaccines based on live or attenuated microorganisms. As a result, millions of people undergoing immunization against specific diseases are injected every year with foreign genes concealed inside bacteria, virus, and the like.8 Although the majority of these genes are probably cleared by the recipient’s immune system, their exact fate and whether they remain functional or not once inside the body is not completely clear.

Another procedure that involves the delivery of a genetic cargo into humans is the experimental use of bacteriophages to treat bacterial infections.9,10 This type of therapy was originally developed by Felix d’Herelle in 1916, at the Pasteur Institute in Paris, and was further popularized by Georgian doctors in the former Soviet Union.11 Again, the administration of bacteriophages in cases of infection with microbes like Staphylococcus aureus or Pseudomona aeruginosa requires patients to be loaded with phages and their genes, even though these are, in principle, expressed only in the invading bacteria and not in the cells of the human recipient.

Although genes are effectively administered to humans as a result of both traditional vaccination and bacteriophage therapy, neither procedure can be categorized as gene therapy. Rather, the conceptualization of human gene therapy as we know it today was fueled by the immense progress made in biochemistry and genetics in the 1950s and early 1960s, which included the discovery of basic concepts in bacteria and bacteriophage genetics, the elucidation of the DNA double helix structure, and the uncovering of the central dogma of molecular biology.

1.1.2 The Coming of Gene Therapy

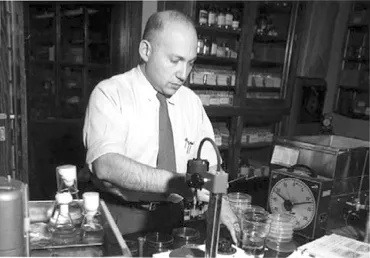

Perhaps no other scientist contributed more to the initial development of gene therapy than Joshua Lederberg, the recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology in 1958 (Figure 1.1). His pioneering work and vision mark him out as one of the greatest in genetics and life sciences.12 Lederberg is to be credited not only for his scientific discoveries in bacterial genetics and plasmid biology but also by his prescience in anticipating gene therapy. This is clear from the 1963 article “Biological Future of Man,” a piece written at a time when, in his own words, molecular biology was unraveling the “mechanisms of heredity.”13 In this visionary article, and among other prospects, Lederberg discussed and hinted at the control, recognition, selection, and integration of genes in human chromosomes. The prediction of a therapy based on the “isolation or design, synthesis and introduction of new genes into defective cells or particular organs” was enunciated in more detail by Edward Tatum in 1966, who even went as far as to envision the concept of ex vivo gene therapy.14 Lederberg and a number of authors elaborated further on the topic in the subsequent years, as described in two detailed accounts of the earliest writings on human gene therapy.15,16 The excitement at the time was such that DNA was viewed by one of the early pioneers as “the ultimate drug.”17

Figure 1.1 Joshua Lederberg at work in a laboratory at the University of Wisconsin (1958).

Downloaded from http://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Joshua_Lederberg_lab.webp.

The first human gene therapy experiments, that is, those that involved the deliberate transfer of foreign genes into human recipients with a therapeutic purpose, were performed in 1970 by the American doctor Stanfield Rogers.16,18 Earlier in 1968, and on the basis of experiments that involved the addition of polynucleotides to the RNA of tobacco mosaic virus, Rogers and his colleague Pfuderer anticipated that viruses could be potentially used as carriers of endogenous or added genetic information to control genetic deficiencies and other diseases such as cancer.19 This belief was put to the test in a highly controversial human experiment, in which Rogers and coworkers attempted to treat three German siblings who had arginase deficiency by injecting them with the native Shope rabbit papilloma virus.18 This attempt was based on previous studies that had apparently shown that the Shope virus codes for and induces arginase in rabbits and in man.20 In the trial, however, and contrary to what was expected, arginase was not expressed from the gene carried by the virus, and the efforts to supplement the missing enzymatic activity failed. Although Rogers’s experiments raised a number of ethical questions, no institutional or legal precepts were violated then since at the time, no specific regulations on gene therapy or institutional review boards (IRBs) existed.21 In spite of the flawed design and consequent failure of this clinical trial, Rogers was one of the first scientists to anticipate the therapeutic potential of viruses as carriers of genetic information.18 That such a gene therapy experiment was attempted before the establishment of recombinant DNA technology in 1973 (discussed ahead in Section 1.2.3) is a tribute to Rogers’s vision.

Exactly a decade later, in July 1980, Martin Cline at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) headed a human trial designed to treat two young women who were suffering from thalassemia. By that time, recombinant DNA technology had established itself as a powerful tool in the biological and biomedical sciences22 (see Section 1.2.3), and a number of techniques for genetic modification of cultured mammalian cells had been crafted, including calcium phosphate transfection.23 Cline’s study was built upon experimental evidence which had shown that murine bone marrow cells could be transformed in vitro with plasmids harboring genes that coded for proteins like the herpes simplex virus thymidine kinase (HSVtk)24 or dihydrofolate reductase (DHFR).25 Once the modified cells were transplanted into recipient mice, those genes were found to be fully functional. This conferred a proliferative advantage to transformant cells when submitted to the pressure of a selective agent such as the anticancer drug methotrexate.24 Recognizing that the techniques for inserting and selecting for expression of genes were as applicable to animals as they were to tissue culture cells, Cline and coworkers reasoned that “gene replacement” could be useful to treat patients with malignant diseases or hemoglobinopathies, such as sickle cell anemia and thalassemia.24

In what was judged by many as a bold leap, Cline then decided to apply these methodologies in a human study of β0-thalassemia, a disease characterized by the inability of the patient cells to synthesize the β-chain of hemoglobin, as a result of mutations in the hemoglobin beta gene. The experiment involved the removal of bone marrow cells from two patients, and their subsequent transformation in vitro with both the β-globin and the HSVtk genes.26 The genes were carried independently by plasmids, and the calcium phosphate methodology was used to precipitate donor DNA and to transform the recipient cells. The higher efficiency of the HSVtk when compared with its human counterpart was expected to provide a selective proliferative advantage to marrow cells once these were transplanted back into the patients. Local irradiation was administered at the site of reinjection in order to provide space for the transformed cells to settle in the bone marrow. However, neither signs of gene (HSVtk or β-globin) expression nor improvements in the patient’s health were detected. Furthermore, and in what was probably the most significant outcome of the experiment, the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in the United States ruled that Cline had broken federal regulations on human experimentation, even though permission had been granted by the foreign hospitals in Jerusalem and Naples, where the two experiments took place.26 Among the consequences suffered, Cline had to resign chairmanship of his department at UCLA, lost a couple of grants, and had all of his grant applications in the subsequent 3 years accompanied with a report of the NIH investigations into his activities of 1979–1980.27

Although both Rogers’s and Cline’s trials were heavily criticized for scientific, procedural, and ethical reasons, their pioneering actions also contributed to the est...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Part I: Basics

- Part II: Applications

- Part III: Manufacturing

- Part IV: Concluding Remarks and Outlook

- Index