![]()

Part I

Origins

![]()

Chapter 1

Plant life: a primer

1.1 An Introduction to Plant Biology

We begin our investigation of how genes, proteins, metabolites and environmental signals interact in living plants by recognizing that readers may approach this subject from different backgrounds. To provide a common knowledge base, we have developed this chapter as a plant biology primer. For readers well versed in the evolution, development, anatomy and morphology of plants, this chapter will review familiar topics. For those not yet exposed to these disciplines, the chapter provides grounding in the biology of whole plants and introduces the plant life cycle on which this textbook is structured. Many of the terms and concepts introduced here will be revisited as later chapters delve into the processes and mechanisms that underlie each stage of plant life, describing the intricate network of cellular, molecular, biochemical and physiological events through which plants make life on land possible. We will be discussing the types of evidence used to develop modern classification schemes, and the evolutionary history and relationships among the groups of green plants alive today. These will provide a basis for the discussion of the fundamentals of plant anatomy, development and reproductive biology.

1.2 Plant Systematics

What makes a plant a plant? This seemingly simple question has challenged biologists for centuries. The science of systematics seeks to identify organisms and order them in hierarchical classification schemes based on their evolutionary (phylogenetic) relationships. The levels of classification range from the domain, the most inclusive group, to the species, the most exclusive group (Table 1.1). Such schemes have predictive value, making it easier to distinguish individual organisms by name and to recognize groups of close or distant relatives. Members of a group of species at any level of classification are sometimes referred to as a taxon (plural: taxa), and the science of classification is called taxonomy.

Table 1.1 The ranks used in the classification of plants, as illustrated for domesticated barley (Hordeum vulgare).

| Kingdom | Viridoplantae (green plant) |

| Phylum (Division) | Magnoliophyta (flowering plant) |

| Class | Liliopsida (monocot) |

| Order | Poales |

| Family | Poaceae (grass family) |

| Genus | Hordeum (barley) |

| Species | vulgare |

1.2.1 Each Species has a Unique Scientific Name that Reflects Its Phylogeny

The scientific name of a plant includes its genus and species names. Carolus Linnaeus developed the genus/species binomial in 1753 as a shorthand version of the long polynomial name he gave each plant in his major taxonomic work, Species Plantarum. Linnaeus's polynomials have fallen out of use, but the binomial system has survived as the cornerstone of all biological classification schemes.

Latin binomials are italicized, with the first letter of the genus name capitalized and the first letter of the species epithet in lower case. Often a specific attribution is added to the binomial. In the case of domesticated barley, Hordeum vulgare, this binomial was used first by Linnaeus, so the abbreviation ‘L.’ is appended in Roman typeface: Hordeum vulgare L. (Figure 1.1). After first use of the full binomial in a document or in a discussion of several barley species, the shortened form H. vulgare can be used.

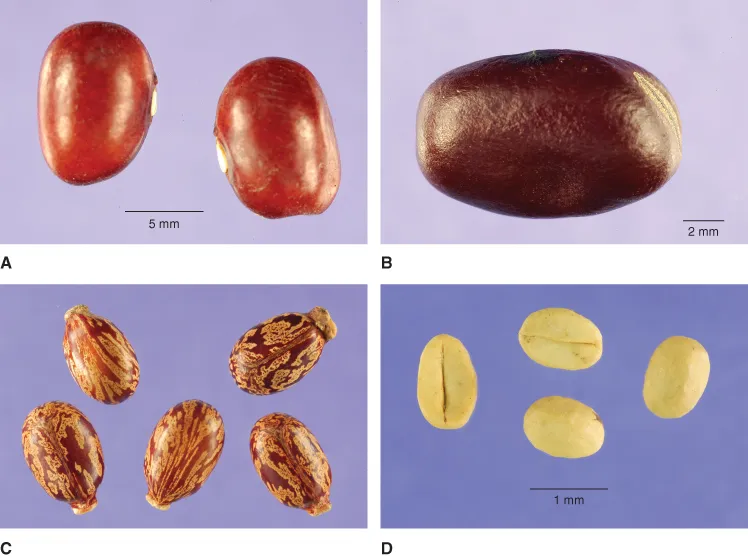

The value of coupling the binomial system to phylogeny-based classification becomes apparent when considering the muddle of common botanical names. Take ‘beans’, for example. The many plants that are referred to as beans do not belong to the same genus, the same family or even the same order (Figure 1.2). The common edible beans you might find on a dinner plate belong to the bean family, Fabaceae, but the plant that produces the castor bean is Ricinus communis in the family Euphorbiaceae, and the coffee bean comes from Coffea arabica, a member of the Rubiaceae. To make the situation more complex, the beans in the family Fabaceae belong to a number of different genera and often have many different common names. One example is Phaseolus vulgaris, a single species whose cultivated varieties produce adzuki, dry, French, green, pinto, runner, snap and wax beans. Other species in the same genus include lima beans (P. limensis) and butter beans (P. lunatus). Another genus in Fabaceae, Vicia, has 160 separate species, including Vicia faba. As you might guess from the specific epithet faba, Vicia faba is the fava bean, but this species is also called the broad, English, field, horse, pigeon, tick or Windsor bean (Figure 1.2).

Plant scientists often encounter the term cultivar, which is used to describe the cultivated varieties that plant breeders produce from wild species. When the cultivar is known, it is denoted by single quotation marks and/or the abbreviation ‘cv.’ and follows the Latin binomial. Cultivar names are in a language other than Latin. They are not italicized, and first letter(s) are capitalized: Hordeum vulgare L. ‘Golden Promise’ is the current convention, but the forms Hordeum vulgare L. cv. ‘Golden Promise’ and Hordeum vulgare L. cv. Golden Promise have also been used.

Key Points

Common names have limited usefulness in identifying plants. The broad bean in the UK is the fava bean in the USA, but this plant is also referred to as the faba, field or horse bean, among other names. Plant biologists use the Latin binomial system devised by Linnaeus to describe species and the binomial for fava bean is Vicia faba. Binomials are written with a strict set of rules. The first epithet, as in Vicia, is the organism's genus and the second, faba, is the species. The binomial is often followed by an abbreviated attribution that identifies the person who gave the organism its binomial. In the case of V. faba, it is followed by L., identifying Linnaeus as the authority. Binomials are abbreviated when they are used repetitively as above, V. faba, the genus denoted by the first letter followed by the full species name. Binomials are also displayed in italic font whereas the authority is typed plain font.

1.2.2 Modern Classification Schemes Attempt to Establish Evolutionary Relationships

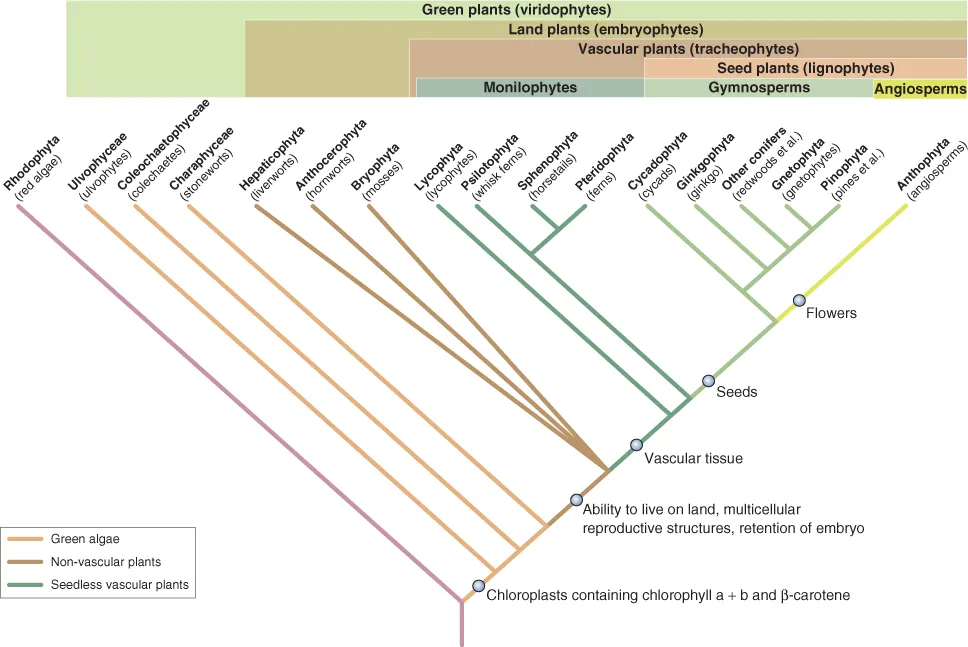

Classification schemes based on phylogeny attempt to construct taxa that are monophyletic, that is, groups that include an ancestral species, all of its descendants and only its descendants. Modern methods of phylogenetic analysis are known as cladistics, a term derived from the word clade. A clade is a monophyletic taxon. In this chapter we will be using evolutionary trees called cladograms (Figure 1.3) to illustrate current hypotheses about the evolutionary history of plants.

To construct cladograms, systematists and evolutionary biologists use morphological, anatomical and metabolic traits as well as biochemical and molecular-genetic data. The tree is rooted using an outgroup, a relative of the taxon under investigation (the ingroup). The ingroup and the outgroup share certain primitive traits; members of the ingroup have acquired new derived traits that distinguish them from the outgroup. For example, in the cladogram in Figure 1.3, red algae are the outgroup for the green plant clade. Red algae and green plants share certain primitive traits, such as having cell walls composed of cellulose (see Chapter 4) and chloroplasts enclosed by two membranes. Chloroplasts of green plants, unlike those of red algae, contain both chlorophyll a and chlorophyll b; the presence of chlorophyll b is a major character that separates green plants from red algae. The remainder of the cladogram is constructed in a similar fashion. At each branch point, the clade above the branch point has derived traits that separate it from the taxa below the branch.

1.3 The Origin of Land Plants

To understand the evolution of the land plants, it is useful to look at their evolutionary origins. Life originate...