- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

The Handbook of Stress: Neuropsychological Effects on the Brain is an authoritative guide to the effects of stress on brain health, with a collection of articles that reflect the most recent findings in the field.

- Presents cutting edge findings on the effects of stress on brain health

- Examines stress influences on brain plasticity across the lifespan, including links to anxiety, PTSD, and clinical depression

- Features contributions by internationally recognized experts in the field of brain health

- Serves as an essential reference guide for scholars and advanced students

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Handbook of Stress by Cheryl D. Conrad in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Industrial & Organizational Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part I: Basics of the Stress Response

1

The Basics of the Stress Response

A Historical Context and Introduction

An Introduction to Stress

Stress is a concept that everybody can identify with and yet, if asked to define stress, most people might indicate that it is synonymous with feeling overwhelmed, anxious, or under intense pressure. To this end, stress is typically thought about from the perspective of what causes it. However, an issue to consider when thinking about stress in terms of its source (i.e., the stressor) is the subjective dilemma that occurs when a stressful event or circumstance is not perceived the same way among different individuals. For example, riding a roller coaster may be a very pleasurable experience for one person while being an extremely unpleasant experience for another. It is unlikely the individual who enjoys the roller coaster would label it as a stressor. Nevertheless, that person’s body undergoes similar internal physical reactions as the individual who perceives the roller-coaster ride negatively, highlighting the caveat that even fun and exciting experiences can be considered stressors based upon the objective methods of defining stress in terms of the neurobiological cascade of responses that underlie an arousing experience. However, a complex interplay between physiological, psychological, and behavioral processes that varies across situations precludes developing a singular definition of stress based solely on the physical response. Thus, both stressor and stress-response elements need to be taken into careful consideration when studying stress as a scientific construct. The goal of this chapter is to provide an introductory overview of these elements, including a brief historical perspective, and highlight the important relationship between stress, emotions, and neuropsychological health.

Although stress is often perceived in a negative light, it is actually a very useful and highly adaptive response. The body understands the importance of stress, but also the potential damage that it can cause, and is therefore equipped with central and peripheral systems that both promote and suppress it (Sapolsky et al., 2000). Activation of these systems (i.e., the stress response) represents an evolutionarily conserved ability of an organism to deal with circumstances that require vigilance, arousal, and/or action (Neese and Young, 2000). In addition to facilitating the perception and processing of stress, the stress response is also designed to restore balance. To this end, the various neurotransmitters, peptides, and hormones that are released in response to stress serve a protective function for an organism (McEwen, 2000b). Importantly, these neurochemical mediators stimulate tissues to respond in an appropriate and adaptive manner to the stressful circumstance at hand (McEwen and Seeman, 1999). The physiological component of the stress response can be further modified by psychological processes, such as coping and appraisal, which can aide in (or potentially hinder) the restoration of balance.

The experience of too much stress over time can have adverse consequences on health and behavior, but never experiencing any stress would result in inactivity, boredom, and an inability to adequately respond to internal/external demands. For instance, stress can be useful to motivate and prepare organisms to deal with situations such as writing a research paper or escaping from a predator. To appreciate the function of stress in a given situation, it is important to consider the stressor. There are a number of internal and external causes of stress, and these are generally characterized into two categories. Systemic (also referred to as physiological) stressors represent a physically based threat to an organism without requiring cognitive processing. Systemic stressors can include internal factors, such as inflammation or hemorrhage, and external factors, such as a burn or bite. Psychogenic stressors represent a more psychologically based disturbance that requires cognitive processing. As such, psychogenic stressors typically involve an anticipatory component along with real-time appraisal. In general, stress has been popularly conceptualized as any physical or psychological event, whether it be actual or imagined, that disrupts homeostatic processes within an organism. Therefore, a more precise definition of a stressor is anything that jeopardizes a state of balance, or homeostasis, within an organism.

The Road to Conceptualizing Stress

In the sections that follow, we will elaborate further on the details of the stress response and the different types of stressors and regulation mechanisms. However, it is important to first acknowledge a few of the seminal findings that have shaped our modern understanding of these concepts, and touch upon one of the current influential perspectives on how the field views stress (i.e., allostasis). The original studies on the physiology of the stress response by Walter Cannon and Hans Selye suggested initially that the body’s reaction is nonspecific in nature, and thus that all stressors in general produce the same ends. For Cannon (1932) the focus was on exploring the sympathetic-adrenal (i.e., autonomic) response to an immediate stressor. His work established that an organism prepares itself to deal with a threat via release of epinephrine (also referred to as adrenaline) from the adrenal medulla, which subsequently activates the body’s energy reserves by accelerating heart rate and blood pressure, mobilizing blood glucose levels, increasing respiration, and inhibiting unnecessary energy-utilizing processes such as digestion and reproduction. The ultimate result is to quickly prime an organism for a fight-or-flight (Cannon, 1929), or freeze, response (Bracha et al., 2004). Notably, Cannon helped develop the concept of homeostasis and stress by postulating that stress disturbs equilibrium, and that the autonomic response helps to restore one’s internal processes (or milieu) to steady-state levels necessary for health and survival in the face of challenge (Cannon, 1932).

Selye (1956) expanded upon Cannon’s work by investigating the other primary system involved in stress: the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal (HPA) axis (i.e., the endocrine system). Namely, Selye focused on the release of hormones (glucocorticoids, GCs) from the adrenal cortex and their role in the stress response. He coined the concept of a General Adaptation Syndrome (GAS), which represents a reliable pattern of physiological reactions that correspond to the body’s attempt to mediate resistance to a threat. The GAS hypothesis consists of three stages: an alarm stage (i.e., physiological activation of the HPA axis and the sympathetic nervous system [SNS] in preparation to deal with the threat), a resistance stage (i.e., the period following the initial reaction to the threat whereby the body mediates ongoing stress and attempts to return to steady-state levels), and an exhaustion stage (i.e., when a prolonged stress response overexerts the body’s defense systems, thus draining it of its reserve resources and leading to illness). GCs were thought to be the primary mediator of the GAS. Because a large variety of harmful, physically based stressors produced the GAS and consistently resulted in ulcers, enlarged adrenals, and a compromised immune system when administered chronically, Selye referred to the stress response as being nonspecific in nature. Thus, whereas Cannon viewed stress in terms of the stressor, Selye’s approach was to view stress in terms of the components of the stress response. Although subsequent work would demonstrate that not all stressors result in the same physiological response (e.g., depending on factors such as type and source of stressor, duration, perception, and appraisal), Selye’s invaluable contribution to the field was to pioneer the exploration of the relationship between GC physiology and stress.

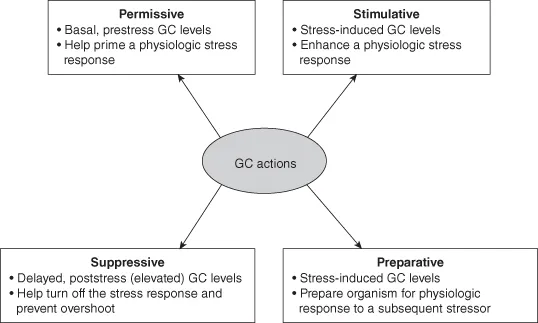

Munck et al. (1984) proposed a novel way to think about the role of GCs in the stress response that countered Selye’s general viewpoint that GCs direct the stress response. Selye’s idea that chronic stress leads to the GAS going awry and causing pathology such as rheumatoid arthritis was not compatible with findings summarized by Munck that GCs produce anti-inflammatory effects and actually provide relief from symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. Munck et al. (1984) therefore hypothesized that GCs work to suppress, rather than enhance, the normal defense mechanisms that are activated by stress in order to prevent these systems from overshooting and seriously threatening homeostasis. In other words, GCs confer protection from the stress response. This hypothesis added to Selye’s traditional view that the body is equipped to adapt to stressors, but had the added advantage of including a role of GCs that was in line with their actual physiological consequences. Sapolsky et al. (2000) updated Munck’s view on GCs to include a more comprehensive set of preparative, simulative, permissive, and suppressive functions of GCs, depending on when examined with relation to the stressor, that further take into account the more rapid, as well as circadian, actions of GCs (see Figure 1.1 and Chapter 2 in this volume).

Figure 1.1 Overview of different types of GC actions with respect to the stress response.

For a more detailed perspective refer to Table 1 in Sapolsky et al. (2000).

The predominately physiological-based concepts of homeostasis and the stress response were given a more psychologically based perspective through the works of John Mason and Richard Lazarus. For instance, Mason (1975) discovered that the GAS response could be modified based on situational and emotional factors, and that psychological interpretation of a stressor is necessary for the subsequent endocrine response to occur. Lazarus (1985) demonstrated that individual differences in various cognitive and motivational variables, such as appraisal and coping, can arbitrate the relationship between a stressor and the stress reaction. Thus, an evaluation of stressors determines their level of threat and their subsequent ability to elicit a stress response. Furthermore, Chrousos and Gold (1992) integrated the concept of individual differences based on genetic factors as an important consideration for measuring the stress response (see Chapters 26, 27, 28, and 29).

The body is designed to react in an efficient manner to the vast array of stressors it may experience. However, this reaction is clearly complicated, containing intricate physiological responses to restore homeostasis that are further modulated by environmental, behavioral, and psychological influences. There are instances (i.e., under intense or chronic conditions), though, when the demands that the stressors exert on the body outweigh the ability of the body to respond without a cost. Certainly over time there is an increasing price the body has to pay when continually trying to restabilize. To address this, a novel concept called allostasis was introduced to the stress field (McEwen, 1998). Allostasis refers to the ability of the body to achieve and maintain stability through change, and represents an adaptive coping mechanism in which various stress response processes are engaged during stress (McEwen, 2000a). Allostasis can be distinguished from homeostasis. In its purest sense, homeostasis refers to maintenance of processes that are essential for survival, and large divergences in these processes leads to death. Homeostasis by itself involves reaching a physiological equilibrium or set point in which adjustments carry no real price, whereas allostasis essentially refers to maintaining homeostasis throughout challenges and involves a network of mediators (e.g., behavioral, sympathetic, and neuroendocrine factors) that can exact a cost when the adjustments have to be maintained outside of their normal range for a period of time. The mediators of the stress response that fluctuate during a demand do not cause death, but rather, they maintain other homeostatic systems within the body, and can be stimulated even by the anticipation of a disturbance. To this end, the term allostasis is useful for illustrating the important distinction that adaptations are in place to promote and maintain survival mechanisms in the body, and that these adaptive responses are not confined to a critical range that implies death when breached. The cost (i.e., wear and tear) that these responses can exert over time, however, is referred to as allostatic load (McEwen, 2000a), and can result from either too much stress output (e.g., adrenal overactivity) or inefficient operation of the stress response system (e.g., inefficient shut-off or having an inadequate stress response to begin with). The key advantage of the allostatic concept is that it accounts for the ability of an organism to be adaptable and maintain its body in an altered state for a sustained period of time. The extent to which this occurs exacts a toll that could eventually manifest itself as a stress-related neuropsychological disorder (i.e., allostatic overload; see Chapters 16 and 17).

Overview of Stress-response Physiology

A detailed outline of the integration and execution of the various components of the stress response is beyond the scope of this chapter, but what follows is an introduction to the fundamentals of the SNS and HPA axis in relation to stress. At the most basic level, the stress response involves a series of SNS and endocrine responses that aim to restore stability within the body and promote the ability of an organis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Wiley-Blackwell Handbooks of Behavioral Neuroscience

- Title page

- Copyright page

- Dedication

- Contributors

- Foreword

- Preface

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Part I: Basics of the Stress Response

- Part II: Stress Influences on Brain Plasticity and Cognition

- Part III: Stress Effects Across the Life Span

- Part IV: Stress Involvement in Anxiety, Posttraumatic Stress Disorder, and Depression

- Part V: Stress, Coping, Predisposition, and Sex Differences

- Name Index

- Subject Index

- Color plates