![]()

1

From plate tectonics to plumes, and back again

Je n’avais pas besoin de cette hypothèse-là.1

-Pierre-Simon Laplace (1749–1827)1

1.1 Volcanoes, and exceptional volcanoes

Volcanoes are among the most extraordinary natural phenomena on Earth. They are powerful shapers of the surface, they affect the make-up of the oceans, the atmosphere and the land on which we stand, and they ultimately incubate life itself. They have inspired fascination and speculation for centuries, and intense scientific study for decades, and it is thus astonishing that the ultimate origin of some of the greatest and most powerful of them is still not fully understood.

The reasons why spectacular volcanic provinces such as Hawaii, Iceland and Yellowstone exist are currently a major controversy. The fundamental question is the link between volcanism and dynamic processes in the mantle, the processes that make Earth unique in the solar system, and keep us alive. The hunt for the truth is extraordinarily cross-disciplinary and virtually every subject within Earth science bears on the problem. There is something for everyone in this remarkable subject and something that everyone can contribute.

The discovery of plate tectonics, hugely cross-disciplinary in itself, threw light on the causes and effects of many kinds of volcano, but it also threw into sharp focus that many of the largest and most remarkable ones seem to be exceptions to the general rule. It is the controversy over the origin of these volcanoes – the ones that seem to be exceptional – that is the focus of this book.

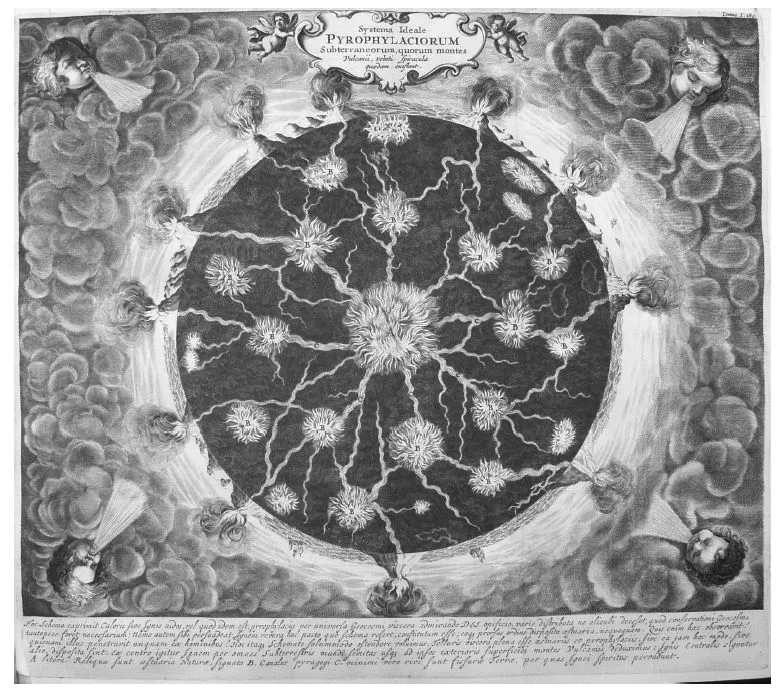

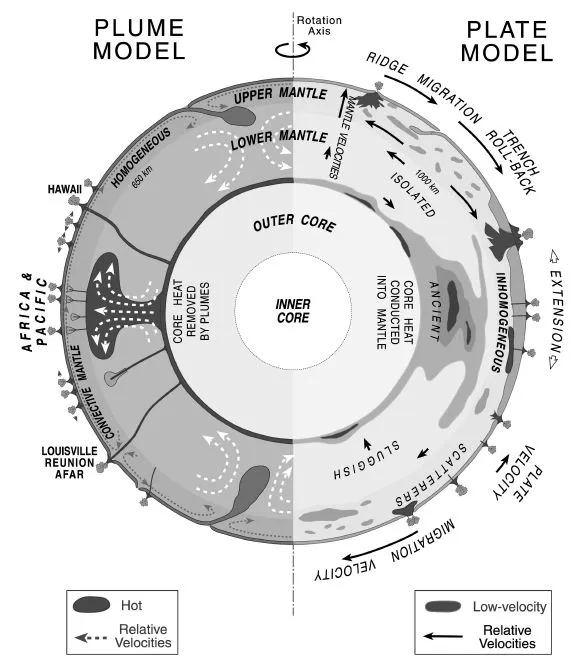

1.2 Early beginnings: Continental drift and its rejection

Speculations regarding the cause of volcanoes began early in the history of science. Prior to the emergence of the scientific method during the Renaissance, explanations for volcanic eruptions were based largely on religion. Mt Hekla, Iceland, was considered to be the gate of Hell. Eruptions occurred when the gate opened and the Devil dragged condemned souls out of Hell, cooling them on the snowfields of Iceland to prevent them from becoming used to the heat of Hell. Athanasius Kircher (1602–1680) provided an early pictorial representation of then contemporary thought (Fig. 1.1) that has much in common with some theories still popular today (Fig. 1.2). The agent provocateur might be forgiven for wondering how much progress in fundamental understanding we have actually made over the last few centuries.

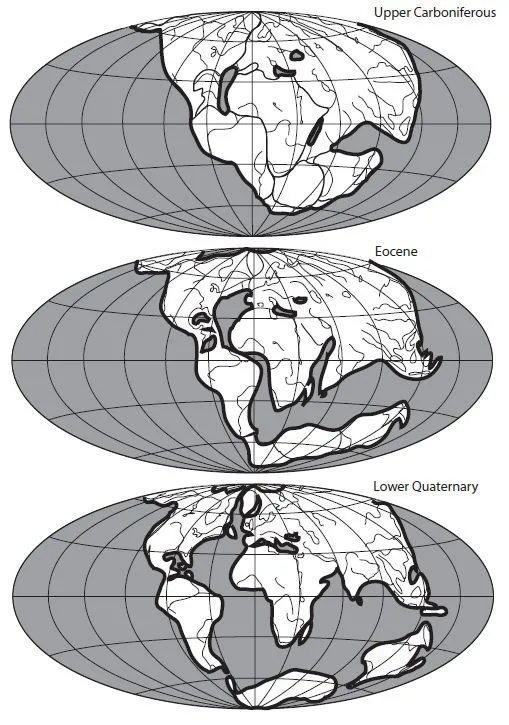

The foundations of modern opinion about the origin of volcanoes were really laid by the work of Alfred Wegener (1880–1930). His pivotal book Die Entstehung der Kontinente und Ozeane (The Origin of Continents and Oceans; Wegener, 1924), first published in 1915, proposed that continents now widely separated had once been joined together in a single supercontinent. According to Wegener, this super-continent broke up and the pieces separated and drifted apart by thousands of kilometers (Fig. 1.3). The idea was not new, but Wegener’s treatment of it was, and his work ultimately led to one of the greatest paradigm shifts Earth science has ever seen. He assembled a powerful multidisciplinary suite of scientific observations to support continental break-up, and developed ideas for the mechanism of drift and the forces that power it. He detailed correlations of fossils, mountain ranges, palaeoclimates and geological formations between continents and across wide oceans. He called the great mother supercontinent Pangaea (“all land”). He was fired with enthusiasm and energized by an inspired personal conviction of the rightness of his hypothesis.

Tragically, during his lifetime, Wegener’s ideas received little support from mainstream geology and physics. On the contrary, they attracted dismissal, ridicule, hostility and even contempt from influential contemporaries. Wegener’s proposed driving mechanism for the continents was criticized. He suggested that the Earth’s centrifugal and tidal forces drove them, an effect that geologists felt was implausibly small. Furthermore, although he emphasized that the sub-crustal region was viscous and could flow, a concept well established and already accepted as a result of knowledge of isostasy, the fate of the oceanic crust was still a difficult problem. A critical missing piece of the jigsaw was that the continental and oceanic crusts were moving as one. Wegener envisaged the continents as somehow to be moving through the oceanic crust, but critics pointed out that evidence for the inevitable crustal deformations was lacking.

Wegener was not without influential supporters, however – scientists who were swayed by his evidence. The problem of mechanism was rapidly solved by Arthur Holmes (1890–1965). Holmes was perhaps the greatest geologist of 20th century, and one of the pioneers of the use of radioactivity to date rocks. Among his great scale and calculating the age of the Earth (Lewis 2000). He had a remarkably broad knowledge of both physics and geology and was a genius at combining them to find new ways of advancing geology

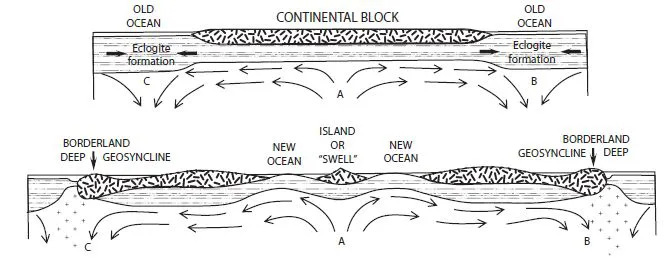

In 1929, Holmes proposed that the continents were transported by subcrustal convection currents. He further suggested that crust was recycled back into the interior of the Earth at the edges of continents by transformation to the dense mineral eclogite, and gravitational sinking (Fig. 1.4) (Holmes, 1929). His model bears an uncanny resemblance to the modern, plate-tectonic concept of subduction. Considering the vast suites of data that had to be assembled before most geologists accepted the subduction process, data that were unavailable to Holmes at the time, his intuition and empathy for the Earth were astounding.

It was not until half a century after publication of Wegener’s first book that the hypothesis of continental drift finally became accepted by mainstream geology. The delay cannot be explained away as being due to incomplete details, or tenuously supported aspects of the the drift mechanism (Oreskes, 1999). The case presented by Wegener was enormously strong and brilliantly cross-disciplinary. It included evidence from physics, geophysics, geology, geography, meteorology, climatology and biology. The power of drift theory to explain self-consistently a huge assemblage of otherwise baffling primary observational evidence is undeniable. After its final acceptance, its rejection must have caused many a conscientious Earth scientist pangs of guilt.

Wegener brilliantly and energetically defended his hypothesis throughout his lifetime, but this was prematurely cut short. He died in 1930 leading an heroic relief expedition across the Greenland icecap, and thus did not live to see his work finally accepted (McCoy, 2006). One can only speculate about how things might have turned out had he survived to press on indefatigably with his work.

Despite his premature demise, Wegener’s ideas were not allowed to die. They were kept alive not least by Holmes who resolutely included a chapter on continental drift in every edition of his seminal textbook Principles of Physical Geology (Holmes, 1944). Notwithstanding this, the hypothesis continued to be regarded as eccentric, or even ludicrous, right up to the brink of its sudden and final acceptance in the mid-1960s. Until then, innovative contributions and developments were often met with ridicule, rejection and hostility that suppressed progress and hurt careers. In 1954 Edward Irving submitted a Ph.D. thesis at Cambridge on palaeomagnetic measurements. His work showed that India had moved north by 6000 km and rotated by more than 30°counterclockwise, close to Wegener’s prediction. His thesis was failed.2 In 1963 a Canadian geologist, Lawrence W. Morley, submitted a paper proposing seafloor spreading, first to the journal Nature and subsequently to the Journal of Geophysical Research. It was rejected by both. As late as 1965 Warren Hamilton lectured at the California Institute of Technology on evidence for Permian continental drift. He was criticized on the grounds that continental drift was impossible, and later that year, at the annual student Christmas party, “Hamilton’s moving continents” were ridiculed by students who masqueraded as continents and danced around the room.

Continental drift was finally accepted when new, independent corroborative observations emerged from fields entirely different to those from which Wegener had drawn. Palaeomagnetism showed a symmetrical pattern of normal and reversed magnetization in the rocks that make up the sea floor on either side of mid-ocean ridges. The widths of the bands were consistent with the known time-scale of magnetic reversals, if the rate of sea-floor production was constant at a particular ridge. Earthquake epicenters delineated narrow zones of activity along ocean ridges and trenches, with intervening areas being largely quiescent. Detailed bathymetry revealed transform faults and earthquake faultplane solutions showed their sense of slip. A “paving stone hypothesis” was proposed, which suggested the Earth was covered with rigid plates that moved relative to one another, bearing the continents along with them (McKenzie and Parker, 1967). Senior geophysicists threw their weight behind the hypothesis and the majority of Earth scientists fell quickly into line.

There has been much speculation over why it took the Earth science establishment a full half century to accept that continental drift occurs (Oreskes, 1999). The reader is urged to read Wegener’s work in its original form – to read what he actually wrote. Wegener had assembled diverse and overwhelming evidence, and a mechanism very similar to that envisaged today by plate tectonics that had been proposed by Holmes. The observations that finally swayed the majority of Earth scientists in the 1960s did not amount to explaining the cause of drift, the most harshly criticized and strongly emphasized weak spot in Wegener’s hypothesis. They merely added an increment to the weight of observations that already supported drift.

It seems, therefore, that popular acceptance of a scientific hypothesis may sometimes be only weakly coupled to its merit. The popularity of an hypothesis may be more strongly influenced by faith in experts perceived as magisters than by direct personal assessment of the evidence by individuals (Glen, 2005). In highly cross-disciplinary fields where it is almost impossible for one person to be fully conversant with every related subject, this may seem to many to be the only practical way forward. However, the magisters, as the greatest will readily admit themselves, are not always right.

1.3 Emergence of the Plume hypothesis

Once continental drift and plate tectonics had become accepted, they proved spectacularly successful. A huge body of geological and geophysical data was reinterpreted, and numerous tests were made of the hypothesis. The basic predictions have been confirmed again and again, right up to the present day when satellite technology is used to measure annual plate movements by direct observation. Plate tectonics explains naturally much basic geology, the origins of mountains and deep-sea trenches, topography, earthquake activity, and the vast majority of volcanism.

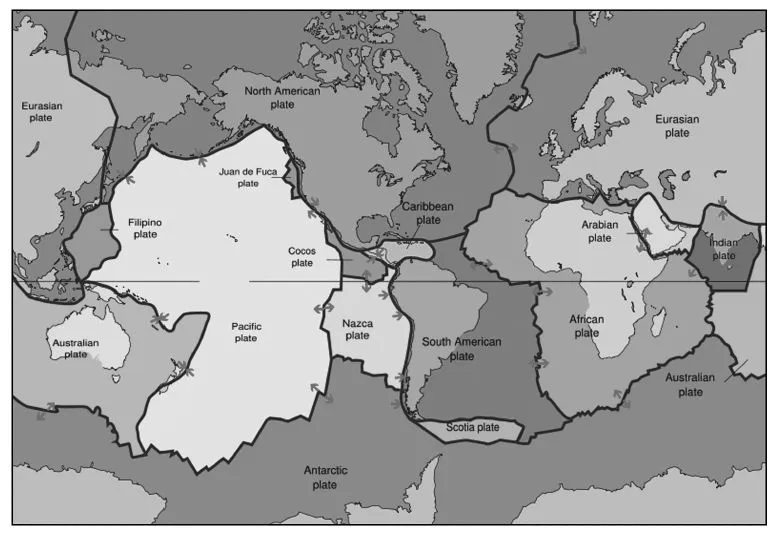

Plate tectonics views the Earth’s surface as being divided up, like a jigsaw, into seven major, and many minor pieces (“plates”). Like the pieces of a jigsaw, the plates behave more or less like coherent units, that is, each moves as though it were a single entity (Fig. 1.5). Oceanic crust is created at mid-ocean ridges by a volcanic belt 60,000km long-almost twice the circumference of the planet. It is destroyed in equal measure at subduction zones, where one plate dives beneath its neighbor and returns lithosphere back into the Earth’s interior. As subductِِing plates sink, they heat up and dehydrate, fluxing the overlying material with volatiles and causing it to melt. This causes belts of volcanoes to form at the surface ahead of the subduction trench. In this way, processes near spreading ridges and subduction zones, where crust is formed or destroyed, a...