![]()

Chapter 1

The Electrostatic Discharge Phenomenon

A lthough a thorough description of the electrostatic phenomenon is beyond the scope of this book and has been covered by several authors (1–4), it might be useful to start by reviewing briefly how static electricity takes place, what are the contributing parameters, and why, eventually, it ends abruptly in its threatening consequence: the electrostatic discharge (ESD).

The following section is an extremely simplified view of the electrostatic charging mechanisms. While clearly not a treatise on static electricity, it illustrate the physics involved, in a simple manner. Readers with a good basic knowledge of electrostatics can probably skip this preliminary portion.

1.1. PHYSICS INVOLVED

Any material is made of atoms. Unless submitted to certain external influences (heating, rubbing, electrical stress, etc.), the atom is at equilibrum; that is, the amount of negative charges represented by the electrons orbiting around the nucleus is exactly balanced by an equal number of positive charges or protons aggregated in the nucleus. Therefore, the net electric charge seen from the ouside is zero.

In good conductors, the mobility of electrons is such that the conditions of equilibrium will always exist; that is, no significant static field will exist between different zones of the same piece of metal. With nonconductive materials, how-ever, the lesser mobility of electrons does not provide such a rapid recombination of charge unbalance. If heated, or rubbed strongly (which also creates heat), a nonconductor will free up electrons.

Depending on the nature of its outer valence orbit, a nonconductive material may be likely to give up electrons or to capture wandering electrons.

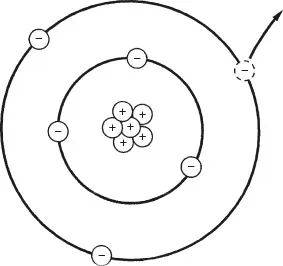

A nonconductive material that gives up an electron, as shown in Figure 1.1, will become positively charged. Such unbalanced atoms with a lack of electrons are called positive ions. A nonconductive material that takes extra electrons will become negatively charged, and its atoms with excess electrons are called neg-ative ions.

Charges with like sign repel while charges with opposite sign attract. There-fore, it seems that nature will rapidly take care of the unbalance by recombining the charges. Unfortunately, while this recombination is instantaneous in metals (i.e., indeed, how a current flows), the high resistance of nonconductive materials makes it unlikely to happen, until such a high gradient of field is reached that either an arc or a mechanical attraction will occur. Besides rubbing or heating, which is the common generation mechanism, an object can become charged by contact with another previously charged object.

This ability of nonconductive materials to acquire electrostatic charges is known as triboelectricity. Once a nonconductive material has been subject to triboelectric charging, the charges trapped on its dielectric surface are not easily removed. Grounding the piece of material will do nothing since, on insulators, charges have no mobility. Only a flow of ionized air, hot steam, or conductive liquid can remove the charge unbalance.

Static charging ability is frequently shown on triboelectric scale, such as the one in Table 1.1 Materials labeled “positive” will take on a positive charge every time they are frictionned against a material lower on the scale. Although this kind of scale is true overall, the precise ranking of each material within the scale should not be definitely relied upon in real-life situations. Many authors and practicians in the ESD community, such as A. Testone (3), have shown how deceptive such triboelectric tables can be.

Table 1.1 Triboelectric Series

| More (+) | Dry air |

| | Plexiglass |

| | Bakelite |

| | Cellulose acetate |

| | Silicon wax |

| | Glass, mica |

| | Nylon |

| | Wool |

| | Human hair |

| | Silk |

| | Paper, cotton, wood |

| | Amber, resins (natural or synthetic) |

| | Styrofoam, polyurethane |

| | Polyethylene |

| | Rubber |

| | Rayon, Dacron, Orlon |

| | PVC |

| | Silicon |

| More (−) | Teflon |

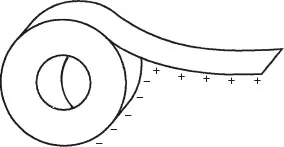

For example, let us take a reel of ordinary office adhesive tape. If we quickly unwind some length of tape, everyone knows that this segment becomes charged and can attract small particles of dust, hairs etc and the like. But since both sides of the tape are the same material, they rank the same (e.g., positive for acetate) on the table, and this piece of film could not develop an electric field against itself.

However, after unwinding this short segment (Fig. 1.2), we notice that it is strongly attracted by the rest of the reel, which indicates that there has been a charge transfer, whereas one side of the tape has acquired electrons that the other side has lost. How can the same material be at the same time a “taker” and a “giver” of electrons, thus contradicting the triboelectric scale? Furthermore, if we cut this piece of tape (using insulating gloves and scissors to prevent our conductive body from influencing the results), and approach it to the reel, some areas of the tape are attracted, while others may be repelled.

The mechanisms coming into play in this apparently simple experiment are multiple and complex. For one, the materials involved are not just acetate against acetate; there is the adhesive layer and also the air itself, which is on the top (+) side of the scale. Then, the tape surfaces have changed their radii as they were separated, such as the “run-away” electrons do not face exactly the same region as when the contact was tight.

Therefore, even two insulating materials of the same nature can eventually develop opposite charges if sufficient friction, shear, or bending is applied. This happens hundreds times a day in a photocopier when foil is slipped over the paper stack.

Thus, although triboelectric scale is a fair indication of the polarity of the charge acquired by materials, we must stay away from peremptory statements when facing an electrostatic charging situation. Static field meters are good instru-ments to get a true measure of the static voltage acquired by various materials.

Now consider the classical example of a person walking on a synthetic carpet, rubbing his body on an insulated chair pad, or moving his nylon shirt sleeve over a polyvinyl chloride (PVC) surface: the farther apart the two materials are on the triboelectric scale and the faster the relative motion of the person, the more electrons will be freed by the givers and captured by the takers. This creates a charge unbalance—hence a latent electric field.

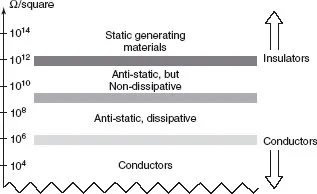

Figure 1.3 suggests a scale of merit for the propensity of materials to create more or less ESD problems. It is based on the surface resistance in ohms per square (i.e., the resistance of a sample square, whether it is 1 cm2 or 1 m2, yields the same results).

Material with more than 109 Ω/square are likely to develop electrostatic potentials that will not bleed-off by themselves due to the high insulation of the material. Materials with less than 109 Ω/square, even if not real conductors, will not keep the charge unbalance very long because recombination will occur through the material itself.

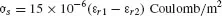

Aguet (5) relates the propensity to electrostatic charge to the dielectric con-stant of the materials that are rubbed. He indicates the surface charge density σs:

where εr1, εr2 are the relative permittivity of the two materials.

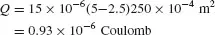

For instance, if one looks at a rubber shoe sole (εr1 = 2.5) representing 250 cm2 and a nylon carpet (εr = 5), the maximum total charge Q that can be acquired is

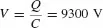

If the corresponding foot-to-ground capacitance C is about 100 pF, the static voltage is derived from

Hence,

It might seem, therefore, that there is practically no upper limit to what voltage a person can attain. Why not 50 kV 100 kV? Richman, in his very illustrative pamphlet on ESD (6), explains that, hopefully, personnel electrostatic voltage cannot exceed 30 kV in the most extreme cases because:

1. The capacitance of the human body, no matter what we do, cannot drop below 30–40 pF, a value that Richman calls our “capacitance to infinity.”

2. Above approximately 25 kV, the corona will start to self-limit our voltage by bleeding off the charge, that is, the assumption of constant charge Q is no longer valid.

So, in most practical situations, the upper range of human body static voltage is 20–25 kV.

Summarizing this short description of electrostatic charging, we can say that static electrification is a complex phenomenon that one cannot solely characterize by any single parameter, such as the ranking of the material on a triboelectric scale, its surface resistivity, or dielectric constant. To the contrary, static dissipa-tion can be dependably related to resistivity.

1.2. INFLUENCING PARAMETERS

Once the type of materials present is known, the most important parameter is relative humidity. It is well known that, during winter and spring seasons, all integrated circuit manufacturers have recorded an increased rate of “infant mor-tality” in their chips, and field engineers report an increasing number of service calls for computer failures.

Several things happen when relative humidity is low:

- Normally, the moisture content in the air tends to decrease the surface resistance of floors, carpets, table mats, and the like by letting wet particles create a vaguely conductive (or say, less than 109 Ω/square) film over an otherwise insulating surface. If the relative humidity decreases, this favorable phenomenon disappears.

- The air itself, being dry becomes a part of the electrostactic buildup mecha-nism every time there is an airflow (wind, air conditioning, blower) passing over an insulated surface.

Many evaluations...