eBook - ePub

Sharing Hidden Know-How

How Managers Solve Thorny Problems With the Knowledge Jam

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Using knowledge that an organization already has is one of the great management ideas of the last fifteen years. Putting Knowledge to Work provides external consultants, internal facilitators, and leaders with a five-step process that will help them achieve their knowledge management goals. The five steps, Knowledge Jams, show how to set the direction, foster the correct tone, conduct knowledge capture event, and integrate this knowledge into the organization. In addition, the author introduces conversation practices for participants to effectively co-create knowledge and discover context.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

KNOWLEDGE JAM RATIONALE: SOLVING THORNY PROBLEMS

“Knowledge Jam Rationale,” describes three thorny knowledge-work problems—“knowledge blind spots,” “knowledge mismatches,” and “knowledge jails.” Knowledge Jam responds to these by insisting on more intentional prioritization and planning, by involving knowledge seekers in choosing and surfacing knowledge relevant to them, and by having a “put-knowledge-to-work” step (not just a repository). I’ll teach you the Knowledge Jam process in Chapter 2, and then expand on Knowledge Jam’s three disciplines in Chapters 3 through 5; then in Chapter 6 I’ll see where Knowledge Jam rejuvenates the manager plagued by thorny problems into a “Bespeckled, Married, Emancipated” hero.

“I could speak volumes about the inhuman perversity of the New England weather, but I will give but a single specimen. I like to hear rain on a tin roof. So I covered part of my roof with tin, with an eye to that luxury. Well, sir, do you think it ever rains on that tin? No, sir; skips every time.”

SAMUEL CLEMENS (MARK TWAIN), AT THE NEW ENGLAND SOCIETY’S SEVENTY-FIRST ANNUAL DINNER, NEW YORK CITY1

Being able to leverage and quickly act on knowledge is the key to your competitiveness—whether you are a for-profit business, a non-profit organization, a nation, or a network. Insights into better manufacturing processes could improve cycle times and position the organization for cost leadership. Marketing insights could point to creative strategies or product attributes that could help to differentiate the brand. Engineering know-how resulting from solving yield problems in one part of your organization could improve manufacturing efficiencies in your other divisions.

But these nuggets only contribute to competitive advantage when there is some effective mechanism for transferring the knowledge. More, such nuggets contribute to sustainable competitive advantage only when we can put know-how to work across the organization just in time. That’s when the process and culture are in place. Then we’re fit to pivot and respond to opportunities, while anticipating change. Many organizations fail to take advantage of their employees’ knowledge or that of the groups with which they collaborate (their networks). Consider these lost opportunities:

Markets

Savvy customers with ever more accessible price and product information negotiate down our margins and demand rapid product enhancement. Even though we know that timely innovation correlates with corporate profits, we often don’t make sense of the new product, market, or channel information that streams across our customer interactions. We realize that insight resides in those of our employees or partners most involved with customers, but only the most agile companies tap it before the market or the competition makes sense of it before we do. For example, airline phone reps may observe that harried flyers changing flights anger because agents ask the same questions each time they change a flight. If only website designers could craft a form that could eliminate the first ninety seconds of the call, flyers would not complain or leave, and millions in service costs could be saved.

Processes

Organizations face price pressure from competitors with lower labor, materials, capital, and transactions costs. For example, engineers tell us that spreading best practice procurement and production processes reduces operations costs. However, we struggle to discern what the best practices are. Seasoned managers are increasingly scarce (due to retirements, layoffs, transfers, and simply overextension). Meanwhile, bits of process knowledge are diffused among many distributed team members, scattered across the organization’s divisions or functions—or even across the supply chain.

Networks

Organizations are interdependent (for example, in expanding markets, cleaning rivers, restoring fish stocks, or reducing carbon emissions). We sense that problems can only be solved collectively, that is, with diverse departments, diverse companies, diverse communities, or diverse nations. However, interpreting multi-organizational problems is often like swimming in brackish water—we can’t see the weeds until we are in them. We feel the presence of other players or policies that obstruct or amplify our actions, but only after time has passed. We struggle to navigate through this murky mix, to understand who’s acting, when, and how the whole system behaves.

In short, as employees, market players, and citizens, we need more timely and efficient approaches to take in and make use of know-how.

WHAT’S NOT WORKING?

Time-worn knowledge “capture” programs—such as “post-mortems,” after action reviews, “lessons learned,” or automated “document-authoring”—often fail because the know-how captured is not representative of experience, is incomplete (or complete at the wrong detail level), or doesn’t get into the right hands. In the rare cases when a capture “event” results in an idea hand-off and a document, the “lessons-learned” fail to inform other teams or divisions without heroic efforts by motivated networkers or by desperate learners.

For example, a team that built a series of four department websites in just six weeks did a post-mortem on the remarkably accelerated process. They spent fifteen person-hours filling a spreadsheet with best-known-methods (“BKMs”). But the spreadsheet failed to inform any other web team (and, ironically, the originating team, themselves). It was difficult to find the final version in the repository, and even when anyone did, he would find that it was labeled with a specific technology version that was being phased out. You’d have to be pretty curious to open it up and dig for the more enduring messages.

Some claim technology, like crawlers and recommendation engines, can solve this thorny problem. But many a KM manager will attest that simply installing technology to bind together people doesn’t guarantee knowledge quality, relevance, or durability. Our tools may very well make us stupid. With ever more abundant technology (like social media, which I’ll be redeeming later!), people are less and less inclined to reflect on and document know-how except in the provincial ways, without considering novel future applications. In modern collaboration-rich environments, we run the risk of operating under the fallacy that all useful truths will float to the “top of the feed” in the course of our blogging, Yammer-ing, or online conversations.

Why are none of these approaches working? After more than a decade of trying, most organizations have two troublesome knowledge issues unresolved.

1. They fail to surface usable know-how.

2. They fail to circulate what they have to those who need it, where they need it, when they need it.

This was Prusak and Jacobson’s premise in 2006 when, at Babson College, they studied knowledge transaction costs for 200 knowledge-workers at US Defense Intelligence Agency, Battelle, Educational Testing Service, and Novartis.2 The researchers measured the entire knowledge-transaction process, starting from the knowledge-seeker’s initial search for experts, then to their negotiating time with those sources, next to their asking or eliciting knowledge, and, finally, to their actually adapting that knowledge to a new problem.

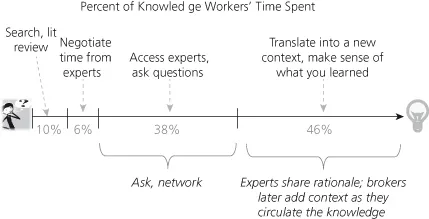

Tellingly, they found that 38 percent of the seeker’s time, on average, was spent drawing knowledge out of experts. Then another 46 percent of the time was spent figuring out how to make use of knowledge in a new setting. The remaining 16 percent—a small share of the knowledge transaction time—was identifying and getting to the experts. Figure 1.1 captures this as a timeline.

Figure 1.1. Knowledge Transaction Time Breakdown

Data reprinted by permission of Harvard Business Review. Percentage of Knowledge Workers’ Time Spent from “The Cost of Knowledge” by Al Jacobson and Laurence Prusak, Harvard Business Review, November 2006, reprint F0611H. Copyright © 2006 by the Harvard Business School Publishing Corporation; all rights reserved.

In one study I conducted for a financial services company doing information technology projects, knowledge transaction costs for U.S. employees working in the United States were in the range of fifteen hours (approximately two person-days per knowledge-seeking event) across the spectrum from searching, through negotiating, through asking, and through translating/adapting. That number went up to two and one-half weeks (thirteen person-days) for India employees working in India on U.S.-based IT projects. Consistent with Prusak and Jacobson’s study, the gap was due largely to the fact that India employees found it difficult to efficiently inquire with their virtual colleagues (for example, about product specifications or code modules), and they had a tough time applying the Americans’ ideas to their unique situation in India. For example, U.S. teams referred frequently to a large U.S. initiative that had been cancelled, and for which few had good documentation. Indian knowledge-recipients would have to seek out the often overworked, beleaguered developer who knew about the dependencies between the initiatives and who could articulate the impacts today. Then the Indian teams would have to figure out what code might be impacted locally back in Bangalore.

Such an analysis is concerning. Why are we putting a lot of our time and energy into not-so-productive interactions? From Prusak and Jacobson and my own experience, it appears that organizations fail to share “hidden” know-how because they start with three faulty assumptions:

1. Managers think they know where the knowledge with the highest economic value resides. They believe that simply pointing knowledge-capture resources (tools, interviewers) at smart people or teams will yield good know-how for solving future problems;

2. Knowledge-originators (experts or teams) think they can accurately predict what subjects or topics or context will be important to potential knowledge-seekers; and,

3. Managers assume that knowledge-seekers are known, or in-waiting (for example, trolling the repository, perusing the blog, or subscribing to the system), and would voluntarily take the time to seek that knowledge out.

From my experience with hundreds of companies, none of these assumptions turn out to be truly accurate. The system needs more than isolated knowledge-originators’ time, knowledge stores, search tools, and faith in seekers’ curiosity. It takes process and participation.

To sense what’s missing, think about these problems as “knowledge blind spots,” “knowledge mismatches,” and “knowledge jails.”

BLIND SPOTS

“Knowledge blind spots” are gaps in our understanding about where knowledge resides or gaps in our awareness that pieces of a puzzle might be spread out among unexpected sources. For most organizations, blind spots are not a concern during business as usual. Subject-matter experts, or SMEs, and their teams are humming along, delivering projects and managing operations. But then, when reorganizations, outages, retirements, or market mishaps occur, our blind spots are exposed. Then managers make a wild dash to identify “who knows” and “what they know.”

Blind Spot 1: Knowledge Flight

Our most common blind spots concern our at-risk employees or teams. In many industries and government agencies, experienced employees are retiring or being downsized, taking their valuable expertise out the door. Meanwhile, experienced teams are routinely disbanding with incomplete knowledge handoffs:

- Retirees leave behind a large gap between themselves and the relatively inexperienced thirty-somethings who comprise the next hump in the demographic camel. Organizations are rightly anxious about losing so much experience, if not the people themselves. Having tried everything from exit interviews to bringing retirees back in consulting roles, they have had relatively little success in retaining useful knowledge or in getting the thirty-somethings to bother accessing the expert knowledge that has carefully been collected for their benefit.

- RIF’d (reduction-in-force) employees may have been targeted because of their span of control (de-layering), their failure to conform to corporate culture, or their unfortunate assignment to non-essential products or services. A friend recounted her recent layoff due to de-layering. A ten-year project manager, she was the human glue for several multi-million-dollar programs. With her departure, out walked the tacit knowledge about how the team worked, who knew what, and who knew whom.

- Transferred employees leave behind a gap, even when their movement is predicted. Much knowledge has lived in the interactions they routinely had with co-workers. For example, they never thought to write down how they learned to collaborate with a demanding boss, a siloed function, or mistrusting supplier or how they managed to persuade leadership to take a risk on a local project. Or it may be that the success that won them the new positions spawns a bit of competition with their previous departments. (A bit more sinister is the transferred employee’s tendency to hoard knowledge and contacts to justify her uniqueness in the new role.)

- Consultants and contractors are often mocked as merely “reading your watch to you” and not providing unique insights. In my experience, this is not usually the case; clients can get a lot of insight out of those temporary employees. They often synthesize a vast store of knowledge about such things as how departments interact, how systems work, how the market influenc...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Praise for Sharing Hidden Know-How

- Title page

- Copyright page

- FOREWORD

- INTRODUCTION

- CHAPTER 1 KNOWLEDGE JAM RATIONALE: SOLVING THORNY PROBLEMS

- CHAPTER 2 KNOWLEDGE JAM BASICS

- CHAPTER 3 DISCIPLINE 1: FACILITATION

- CHAPTER 4 DISCIPLINE 2: CONVERSATION

- CHAPTER 5 DISCIPLINE 3: TRANSLATION

- CHAPTER 6 BESPECKLED, MARRIED, AND EMANCIPATED

- CHAPTER 7 KNOWLEDGE JAM HERITAGE: PREQUEL TO THE THREE DISCIPLINES

- CHAPTER 8 COMPARING KNOWLEDGE JAM TO OTHER KNOWLEDGE-CAPTURE METHODS

- CHAPTER 9 BUILDING A KNOWLEDGE JAM PRACTICE

- CHAPTER 10 KNOWLEDGE JAM FOR LEADING CHANGE AND LEVERAGING SOCIAL MEDIA

- CHAPTER 11 AN INVITATION

- APPENDIX A KNOWLEDGE TYPES

- APPENDIX B KNOWLEDGE JAM TEMPLATES

- APPENDIX C GLOSSARY OF TERMS

- APPENDIX D CASE STUDIES

- APPENDIX E KNOWLEDGE JAM PRACTICE FAQS

- ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

- THE AUTHOR

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Sharing Hidden Know-How by Katrina Pugh in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Management. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.