![]()

1

Life’s Little Lessons

When I was in the second grade, my grandpa told me that if I were able to shake salt on the tail of a bird I would be able to catch it, easy as pie, if only I could just get the salt on its tail.

This excited me to no end. It was all I could think about, so I got a saltshaker and went outside. Even though I hadn’t thought much about it before this, I decided I wanted a pet bird, and wondered who had been keeping this valuable information from me until now. There was something magical about the idea of capturing the mind and body of a bird. I imagined going to school with a bird that sat on my shoulder and ate from my hands. He’d live in my bedroom perched on a stick just waiting to join me in whatever adventure we’d have that day. I couldn’t wait to see it up close and to feel the feathers. I wasn’t sure how the salt on its tail changed a bird’s mind but I was willing to try my grandpa’s advice.

I spent the day creeping up on every bird in the neighborhood. I was patient. But soon I learned that most birds weren’t really on the ground where I was, and so I started climbing trees, stretching out, waiting, hanging from branches, putting myself at risk. This went on all day and into the next. I was singly focused, and worked toward that reward. Soon I realized that getting the salt on the tail of a bird was impossible for a kid to do. Maybe I was just too young. I wondered if anyone ever really got so close that they were able to actually get that salt on a tail. Eventually, I started tossing salt at birds but that just made them fly away.

After a couple days I asked my grandpa about this and he explained that a bird isn’t about to let you get close him, and if he let you get close enough to put the salt on his tail then you were also close enough to catch the bird. I felt a little ripped off, but at the same time I now understood. By then his lesson was making sense and the two days I spent trying to get salt on a bird’s tail didn’t seem like a waste to me. I had to let the short-lived dream of having a trusty bird-mate fade away, but I thought that somehow I was a little smarter because of it all. In fact I remember telling other kids at the time what I’d been up to and that it really was a bit of a mental trick, a play on words, and I became proud of the fact that I understood the more subtle lesson. They didn’t understand because they hadn’t spent two days trying to actually do it.

I never regretted the time I spent trying. In fact, I spent a lot of time in thought, and considerable time thinking of other ways one might catch a bird. I even designed and set a couple traps when I figured out how hard it was to get the salt on the tail. I got creative and for those two days, I believed in the goal enough to work pretty hard at achieving it.

It’s a funny story to remember at this point in my life, but I do, along with a hundred other stories where I literally dogged it, trying to figure a way to reach my goals. My life is filled with these stories that hold within them precious lessons, advice, and experience. Some are simple, and some took years to unfold, but the experiences went into my quiver, and either a skill, attitude, or habit was put away, to be utilized at some future date. I will share these stories and their lessons in this book.

I often wonder why it is that as children we will work to death on a project, but then as we get older we give up so easily. I realize we are each wired differently, but this pattern is common with so many people. I can’t answer the question of why some of us will figure things out and some of us won’t, or why some of us will work until we get it and some of us won’t, but I can say that those who are willing to work toward their goals and learn, will eventually get there and accomplish something above average.

Nearly all of us can think back to the simpler times of our youth when we were passionate about an idea and worked on it as though we were going to be successful. What if those youthful passions had been nourished and exercised from the very first days? How far along the paths to their dreams would many people be? What if you could help revive or redirect your efforts back into some of the passions and interests that were lost along the way? Or if you could simplify what needed to be done to get closer to where you want to be?

How’d You Know?

Often people ask me how I discovered my passion. It didn’t happen that I was walking along and all of a sudden, wham, a bolt of lightning came out of the blue. Yet many feel they haven’t been so lucky as to hear their calling about what to do with their lives. They express that if they had met their lightning bolt, then maybe they would have more meaningful lives.

Many people think my passion is music, that I’m nuts about guitars and that my life was a long road of playing guitars and becoming an expert on music. Most people who follow that path become famous guitar players, not famous builders. My passion, instead, is making things, understanding how stuff is made, and figuring out how things work.

I’ve broken nearly everything I’ve ever owned at one time or another, trying to figure out how it works. There was the folding travel alarm clock that my folks bought me for Christmas that by the next morning wasn’t working right because I’d disassembled it. I took it apart and put it back together, and through that I got a great look at the inside of a clock. Maybe the only lesson I learned was to not take a new clock apart, because it never really worked right after that. One might think that was careless and disrespectful, but I disagree. I learned how disappointed I was to have a clock that worked and then a clock that didn’t. I also learned to take things apart more carefully in the future. I managed to make it work well enough.

With experience one can learn how to look at things and find out how they come apart and go back together. By learning how other people make stuff, it will help when one day you’re learning how to make your own stuff. I’ve experienced as much as 30-year gaps between learning something and applying it. It’s not always immediate.

I also learned that you can’t let the speaker wires on your stereo touch each other or they will short out and you might blow the amplifier. There are some amps that will and some that won’t. The stereo that I worked all summer to earn the money to buy when I was in seventh grade was one of those that gets ruined when you touch those particular wires together. I found that out just a couple days after buying it while trying to hot-rod some other speakers. I looked at the inside of it for hours, because I’d fixed some similar things like it before by looking and thinking and finally seeing something that was off. But this one needed a pro, so my dad took me to get it fixed. I learned a lot by breaking that stereo—mainly how to be more careful in my exploration. This comes in handy when your car acts up and you have to look and observe carefully to get it going again, and you simply can’t afford to break it by careless exploration into the problem. Other people learn different things by breaking something. They learn to stop taking things apart, or they learn to hire a professional, and that professional would eventually be me, or someone like me.

I learned how to take my friend’s bicycle brake apart slower and more quietly than I took mine apart, being more observant and more deliberate. Like defusing a bomb in a movie, you have to be quiet and thoughtful and pay attention.

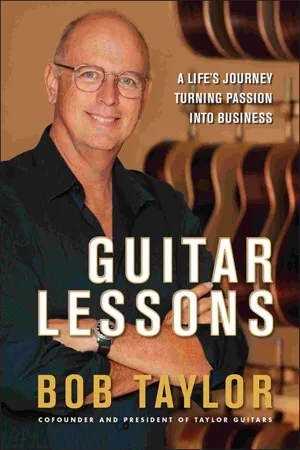

So my story is about how my interest in building things and my interest in playing guitars merged, and how to this day the two burn off each other like two logs in a fireplace. It’s about how I took a talent and an interest and combined them into one, where they both could be nurtured and where I could gain satisfaction from the work. And it’s about learning to make a living from doing what seems impossible, namely, starting at the beginning, with no assets and working until it grows into something. And there was a lot to figure out, not just the guitar, but the machines, the factory, the employees, the government, the marketing, the sales, the finance, the R&D. I’ll say right now that it took two of us, my partner Kurt Listug and myself to tackle all that needed to be learned. Kurt figured out the marketing, sales, and finance, while I figured out the guitars, the factory, and the training of people.

Get in Line

My colleague and friend Greg Deering, of Deering Banjos fame, has been involved with the Boy Scouts of America for most his life. When organizing his troop for an activity he says, “Okay, form two lines. This one on the right is the ‘I can figure this out myself line’ and the one on the left is the ‘I have to have someone show me everything about it line.’ ”

The amazing thing is that some actually get into the “show me everything about it” line. They do that willingly; they make that decision for themselves, and take the reward that is appropriate for that effort. We all have interests we want to learn about or put effort into and other things in which we’re just not interested. When you’re involved in something you enjoy, and you’re there for a purpose, how much effort do you put forth? For me, there are activities that I am willing to dig into, work toward, and learn about—those are the things I am passionate about.

That willingness to figure out how to do things on my own might have been why I cut the neck off my first guitar. I had no fear of trying things on my own. I also knew that I wouldn’t get in trouble for trying. My friends would have gotten in big trouble, but their moms and dads didn’t make things like my folks did. My mom sewed clothes and my dad fixed things around the house, built furniture, and worked on the car. My folks also didn’t buy me much stuff, so I had to either learn how to make things or earn some money to get it on my own.

There seems to be a lot of formulas for success out there, and most of them are true and have much merit. But one thing that is common to just about all the stories is the positive effect that work and experience has on your success. Now, there are many things that can thwart the work, and they might not be your fault. Nevertheless, people who, one way or another, manage to get a lot of experience in an area of interest usually get good at it.

![]()

2

My Very First Guitar

My dad, Dick Taylor, was a seaman in the Navy when I was growing up. He eventually retired as Interior Communication Electrician, Senior Chief Petty Officer, right about when I graduated from high school, but with four kids at home there never was much extra money for my parents to buy all the things we might ask for.

I bought my first guitar from Michael Broward when I was in the fourth grade. He was older than me and already knew how to play guitar. He lived across the street from the house I grew up in and I used to stand in his garage and watch, as he’d strap on that electric guitar and plug into an amplifier on the floor. It was small, maybe knee-high, and he’d plug a microphone into it as well. Then he’d play “Wipe Out” or “Ghost Riders in the Sky” or my personal favorite, “Mrs. Brown You’ve Got a Lovely Daughter.” He even sang the word “douaghtah” just like Herman did.

Next door to Michael was another kid and one day we all ended up in the garage singing folk songs. In fact, they started talking about starting a group, and they even had tryouts. We had to audition by singing “Michael Row the Boat Ashore” to each other. I tried out, but I can’t remember if I made the cut. I do remember that we were all still friends the next day.

After tryouts, Michael showed me an acoustic guitar he had and said he’d sell it to me for three dollars. I’m not sure where the money came from but I bought it and took it home. Playing chords was a bit of a stretch for me, and I don’t remember learning how to tune the guitar but I do remember learning how to play “Green Onions” on the low strings and “Wipe Out” on the high strings.

At that age, there were forts to build and bikes to ride besides the guitar playing and I made time for all of that as well as building models. I loved watching monster movies on Saturday afternoon TV, and I had all the monster models. There was Frankenstein, Dracula, The Mummy, Phantom of the Opera, and the Creature from the Black Lagoon. I had accumulated a pretty good collection of Testor’s Model Paint and some small paint brushes from those models.

This was when I noticed that the white lines along the edge of my little guitar were painted onto the guitar, and that there were some dings and scratches in them. I got out my white paint and a brush and painted over the dings, but the white didn’t match. It’s amazing how many colors of white there are. Well, the guitar looked worse rather than better so I sanded off the paint I’d put on and the problem grew. Before long I had masked off the entire guitar and sanded all the painted binding away and repainted it totally. This time there were ugly brush strokes so I started over. In all, I think I spent a week and three attempts before I got the white binding painted back on and was satisfied. I should have just left it alone, but that wasn’t in my nature.

I spent more time messing around painting and sanding that guitar than I did playing it. But its playing days were numbered once I rode my bike to Apex Music and fell in love with a little electric pickup on a pickguard in the showcase. It was probably twenty-something dollars, but I wanted it bad. I thought that an electric guitar like the one Michael had would suit me better so I would make my acoustic guitar electric. Maybe I had played his and found it easier, or maybe I just thought he was cool, but I think mostly I was interested in the guitar itself. I remember imagining how cool I’d be with a bird on my shoulder at school, but I never remember thinking that about playing guitar. I wasn’t interested in guitars to be cool or to impress a girl. I was just interested in the guitar for itself.

There was no sense in buying the pickup right then and I didn’t have the money anyway, but that didn’t mean I couldn’t prepare the guitar. So I took a deep breath and sawed the neck off, trying hard not to ruin the neck in the process. The neck was what I wanted. The acoustic body had to go in order to allow me to put a solid wood electric guitar body onto the neck, add the pickup, and end up with an electric guitar in the end. Some onlooker or naysayer would think it a careless act, but it was filled with care. I planned that neckectomy for days and finally performed it successfully.

Off to the Boy’s Club in San Diego I went with my guitar neck strapped to my bike; the one and only bike I ever had in my youth. It lasted me from the second grade all the way to my driver’s license. I repainted it four times; I re-spoked the wheels, rebuilt the brakes, and had to find a garage to weld on one of my pedals because the threads of the crank were stripped. I learned a lot working on that bike. In fact, one time I took the ...